French charm

“All the charm of France

was on her face.

Like the Virgin Mary,

she was full of grace”

I remember learning that poem at school. It´s by a Mexican poet, Amado Nervo. The teacher asked me to read the lines aloud in front of the class and I have never forgotten them since. They may not be the most beautiful verses ever written, and their meaning –how could France be on anyone´s face? – certainly seemed puzzling to me back then, but there is something memorable in them. Whatever it is, the relation between “France”, “charm” and “grace” was destined to endure.

France had long been part of both my vocabulary and my imagination due to my aunts Regina and Josefa, “the French ones”, as my mother used to call them. They lived in Bordeaux and came to visit us from time to time. I remember going to say goodbye to them at the station in Barcelona, called very appropriately “Estación de Francia”. I loved the excitement that aroused in me the hustle and bustle of travellers under the magnificent glass and wrought-iron girders of the cathedral-like building, with its luxurious great hall and high vaults. The very name of it awoke in me a desire for foreign lands where different languages were spoken, and different customs were had.

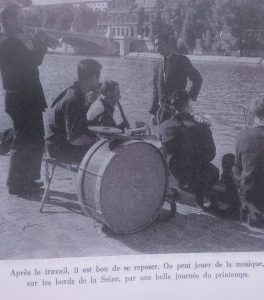

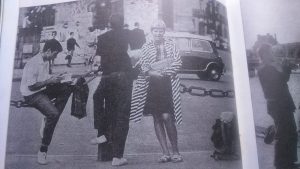

The “glamour” that those verses conjured in my juvenile mind, and that I would later discover is an essential part of how that country likes to present itself to the world, combined with that of my sister´s French book, “El francés por la imagen”. It was full of images of a France that had already gone by then, a country of elegant girls who wore gloves and dressed in Christian Dior or Chanel suits.

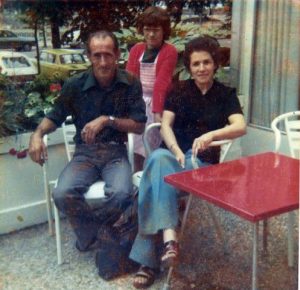

Like so many Andalusians, my family migrated north in the late fifties and early sixties of the last century. My paternal grandparents, Josefa and Manuel, had eight children, six girls and two boys. Of them, only my aunt Ana and her family would stay in their birthplace, Pozoblanco, north of the city of Córdoba. As they grew up, all of them realized that there was no future in the subsistence economy to which Franco´s disastrous policies had condemned rural Spain.

My aunt Regina, the oldest of the eight siblings, married my uncle Antonio Egea and in 1957 they moved to France with their three daughters, my cousins Mercedes, Josefa and Tony. Uncle Antonio, “el Egea” as we always called him at home to distinguish him from the other uncle Antonio, the husband of my aunt Nicasia, was a skilled charcoal burner.

Charcoal was the main source of fuel in the Pedroches area, whose capital is Pozoblanco. As he was a capable and shrewd businessman, uncle Antonio Egea made money and invested it in purchasing mules so as to became a muleteer, a profession that was still current in Spain at that time, since the civil war had left the country with practically no access to petrol.

He came from staunch Republicans who had been massacred by the rebellious fascist troops. He felt suffocated under the victorious fascists, so he decided to emigrate to France as soon as he could. His brother Bonifacio, uncle Boni as he was called by my cousins there, had gone into exile in Bordeaux at the end of the war. It was he who told Antonio that in the Landes area, south of Bordeaux, expert charcoal burners were much in need and that one could make good money on it. So that was how my aunt Regina ended there.

The Landes had been for centuries an extensive marshy area where malaria was rife. The soil was poor and so were the shepherds that toiled there. But Napoleon III, following a plan previously designed in the times of the Revolution, transformed it into the largest forest in Western Europe and one of the largest on the continent. Hundreds of thousands of pine trees were planted to help dry up the malarial lagoons and to settle the quick soft dunes that abound in the region. Traditionally the peasants had walked with long stilts on the muddy terrain.

With the wood of the pines a prosperous furniture manufacturing industry developed and with the wood that was no good for that purpose, charcoal was made. As in Pozoblanco, it was the only source of fuel for the inhabitants of the region. So, this is how a branch of my family, who had been so firmly rooted in the Andalusian sierra, would take root in France, inserting themselves in the history of that country.

Like the rest of Europe, France had been in economic trouble after World War II. The gradual loss of her colonies over the following decades would further exacerbate those problems. However, thanks to the help of the Marshall Plan and some soft loans that she received after the Bretton Woods agreements, she managed to implement a development plan and achieve a sustained growth.

Those programs transformed French society into a consumer economy organised along the American model, which France embraced with the same zest as Johnny Halliday embraced rock´n´roll. Wages increased enormously, as did the country´s general wealth and workers´ welfare. The hardest jobs, those that were worst paid or those that people considered less prestigious, were abandoned by the French as they found work in the new service economy. This attracted many immigrants, both from southern Europe and from the former colonies, who came to occupy the productive space abandoned by the natives.

Uncle Antonio and my aunt Regina arrived in France with their three daughters in 1957. As he was smart, he quickly took control of the charcoal business in St-Symphorien, the town of origin of the writer François Mauriac, close to Bordeaux, where the family settled. My uncle became a foreman and acted as a middleman, offering work to many fellow-countrymen from the Pedroches region who were looking for an economic opening far from the stagnation of Spain.

Thanks to him, many arrived in France with a contract that allowed them to legally settle in the country. These immigrants came carrying just a few clothes in a suitcase at first. They suffered harsh conditions, lodging in shacks until they earned enough and learned the French necessary to fend for themselves. My uncle helped them. They often came alone and only once they had settled a bit they brought the wives and children that they had left behind in Spain.

In 2014, my family had a great gathering in St-Symphorien. Then I had the opportunity to know this story first-hand from the mouth of my aunt Regina, who took us to the local cemetery where her husband is buried. He died in 2001. In that cemetery, there were many Spanish names written on the tombstones and my aunt told us who had been brought by her husband and who were already exiled from the Civil War.

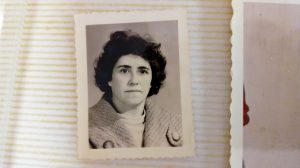

My aunt Josefa and her husband, Uncle Miguel, arrived in Bordeaux the following year, in 1958. Aunt Regina and uncle Antonio had secured a contract for them as keepers in a “chateau” in the region. In Bordeaux, they would have three children, my cousins Jeanine, born in 1959, Manuel in 1960 and Virginie in 1966. Despite how hard it was for my aunt to adapt to her new environment in a language that she did not know, they never looked back, for they immediately understood the profound difference between the country at which they had arrived and the sad reality they had left behind.

It had been difficult for Uncle Miguel to get a passport to leave Spain, for he belonged to a family that had been blacklisted by the dictator´s regime. In the vengeful Spain of General Franco, children had to answer for the alleged crimes of the parents. As a son of a “red”, as the Francoists called anyone that had fought for the Loyalist side in the Spanish Civil War, he was deeply suspect and undeserving of the privilege of a passport. Uncle Miguel’s father had been unceremoniously assassinated by the fascists. His body has never been found. It is one of the thousands that lie by the ditches of Spain or buried in the mass graves scattered throughout the country.

My aunt was already pregnant with my cousin Jeanine when they moved to France. The trip from Pozoblanco was arduous: first they travelled to Madrid, from there to San Sebastián and then to Hendaya, always on the rickety old wooden trains that took forever to cross the huge Castilian plains. They had agreed with my aunt Regina and uncle Antonio that they would meet them at Bordeaux station and help them to get to the “chateau”, but it was already dark by the time they crossed into France. They could hardly see anything through the windows, so they panicked at not knowing where they were and being unable to make themselves understood. A very kind man who was traveling in the same car, and who understood a little bit of Spanish, tried to help them. They showed him the contract with the address of the chateau and the man, understanding that they wanted to get there and not to Bordeaux, urged them to get off the train at the station that came next, which they did, only to find themselves on an empty platform not knowing what to do or where they were. Luckily, at a hotel in that small town they called them a taxi driver who spoke Spanish and drove them to Bordeaux, where they finally met, God only knows how, with aunt Regina and Uncle Antonio.

Life was not easy for them at first. They came with a métayer contract, what is called a sharecropper in English. They had to take care of the vineyards and, in exchange, as well as a salary, they had free accommodation and some free produce. Uncle Miguel seems to have been quite useless at agriculture. Also, since he spoke in Spanish to the horse that pulled the plough, a language that the French horse was evidently not used to, it was difficult for him to handle it. “Don’t let them see you scold the horse,” urged him my aunt, fearing that Uncle Miguel’s incompetence would be exposed and that they would end up fired, after all the hardships endured to get there.

With little schooling and no word of French, aunt Josefa lived in a continuous state of alert. One day she craved one of the cabbages that they were picking in the field. Since she was pregnant, she hid it under her blouse to eat it later at home but, when they got back, there was a couple of gendarmes waiting for them. She almost died of the fright, convinced as she was that someone had denounced her for stealing the cabbage and that they were coming for her. In truth, the police only wanted them to sign some immigration papers, but that shows the unease in which they lived during those first years in France

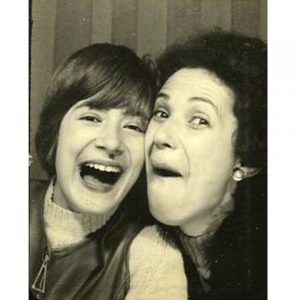

“Aunt Josefa”, I asked her once, “How did you learn French?” “With many tears, my child,” she replied, remembering the many nights she returned home from working as a cleaner overwhelmed for not being able to communicate with people and feeling terribly vulnerable and isolated.

My cousin Jeanine was born in March 1959. According to her, this implies that her parents had married due to circumstances, so her mother did not wear the traditional white dress, customary in those days in Spain. Jeanine was born in a hospital in Bordeaux. Shortly after that, they moved to La Brède, a town famous for being where the philosopher Montesquieu was born and where he lived in his later years. From there, they moved to Lacanau, by the Atlantic Ocean, and then to Mistre. Later they lived in Le Temple and in Louchats, all in the same Landes region, where uncle Miguel worked making coal. My cousin remembers how the resin cans were collected in Louchats, especially a man who limped from a wound he had sustained in the First World War, which made a lot of impression on her. Then they moved to Le Porge, a coastal town, settling finally in Saint Médard-en-Jalles, where aunt Josefa still lives.

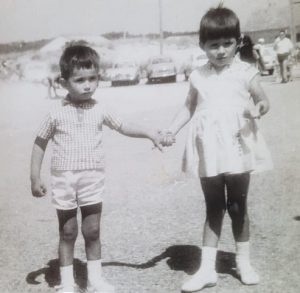

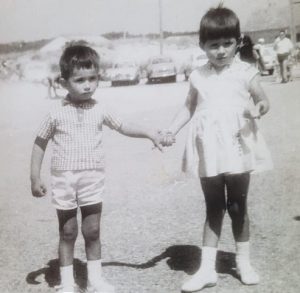

Jeanine started school without speaking a word of French, at age three. She did not understand anything and had a hard time because the children laughed at her. She recalls how at the school she attended in Le Temple she had a box of coloured pencils that had an elephant on it and how her classmates would steal them. Perhaps it is that box that triggered her taste for art. Cousin Jeanine now lives in Barcelona, where she arrived in the late 1970s to study Advertising Drawing at the Escuela Massana. There she met who would be her husband, Quim, and she settled in Barcelona.

Jeanine was the first in the family who mastered the language of her new homeland. For years, she would be the one who dealt with most official business. Her brother Manuel took longer to learn it. She laughs remembering how, when they argued and came to fisticuffs as children often do, she shouted at him: “arrête!” (stop!), but Manuel misunderstood it for the Spanish “cagueta”, meaning wimp, and he would run to their parents crying, complaining that she had insulted him.

Aunt Josefa and uncle Miguel had met when she was serving in the home of a wealthy family in Pozoblanco. Apparently, the ceiling in one of the rooms had collapsed because it was an old house and the owners failed to maintain it properly. Uncle Miguel was the one who came to repair the roof damage and that’s how their romance began.

They were extremely brave to have left not only their hometown and everything they knew and had held dear, but their language too. It shows an admirable courage. However, it is true that they did not find France easy to begin with. The language barrier was a formidable obstacle. From the start, uncle Miguel had wanted to return to Spain, but my aunt had been adamant that they should stay. “Can´t you see that they have electricity here, food, running water and cars?”, she told him. “We’re not going anywhere”.

Uncle Antonio and aunt Regina were very helpful to them. They loaned them eighty francs to start their new life as sharecroppers and gave them clothes and other necessary items. In their new position, aunt Josefa and Uncle Miguel were entitled to eggs, one litre of milk per day, and ten or twenty litres of the wine they sold. They had arrived in France practically with what they had on, for they had sold what little they had owned to pay for their trip. They had no clothes fit for work. Aunt Josefa laughs remembering that she did the farm work with a coat that aunt Regina had given her and in her high heel shoes, which were the only ones she had, all splendidly surreal. My uncle oversaw the ploughing with the help of the famously monolingual horse, while she took care of the vineyard.

Whatever were Uncle Miguel’s agricultural deficiencies, both had been used to working hard in Pozoblanco and they did so in France. They were well regarded by their employers because, according to my aunt, French workers at the farm spent a lot of time chattering and worked little. Although they were in better conditions than those they had left behind in Spain, uncle Miguel missed the bars and the convivial lifestyle he had known back home. But he would eventually take roots and he is buried there now, together with his son, my cousin Manuel.

Although aunt Regina and uncle Antonio´s settling had not been so hard, they also had their bumpy start. The instigator of it all had been Antonio’s brother, Bonifacio, uncle Boni, as my cousins call him. He had fought with the Republicans on the Ebro front and, when Barcelona fell to the fascists, he was one of the 21,000 Spanish refugees who had fled to France and were interned in the infamous fields of Argelès-sur-Mer.

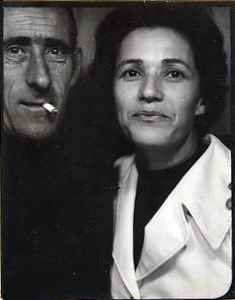

Cousin Jeanine remembers him as fun and elegant, “très charmant”, a cigar always in his mouth and wearing several gold rings in his fingers. He married a French lady, Daniele, who was also very jolly. She was like Edith Piaf, immaculately turned out, always made up with fiery red lips. They made a lot of money selling clothes in a shop they owned in Bordeaux near the Place de la Victoire, as well as selling in local markets out of a van they owned.

Boni was quite a character. He was fiercely left-wing, intellectual, and sharp-witted. Uncle Miguel found himself somewhat out of place in his company. My cousin Jeanine remembers her father and uncle Antonio always arguing, although not in a nasty way. They were so different that they did not really compete. Uncle Antonio wound him up, for example, accusing uncle Miguel of being a lightweight who lacked drive, but he did not flinch, because what he did not understand was the other’s boundless ambition. But they got along well and always helped each other. Family loyalty is a characteristic of the Peñas clan. Also, they both had a taste for partying, good eating and better drinking, so that ultimately brought them together.

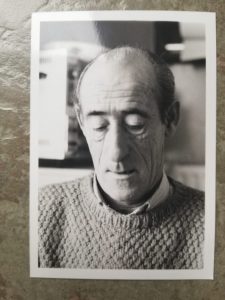

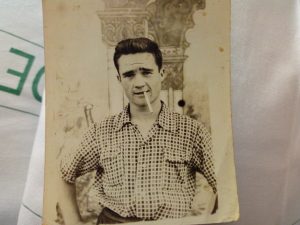

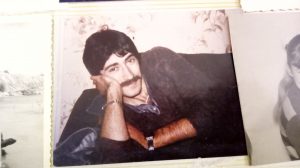

Uncle Antonio was a very smart and capable man. He liked to boss around and to stand out. He was extremely good at managing people, which explains his success at business. My father called him Al Capone because he was always very stylish and liked to wear a fedora hat like the gangsters in the movies. She was also fond of large and luxurious cars; he loved flamenco and he partied hard. He also was something of a womaniser, which sometimes made my aunt Regina suffer, for she was not so keen on his hard-partying ways. In that sense, he was the opposite of uncle Miguel, who was content to live modestly and with as few complications as possible

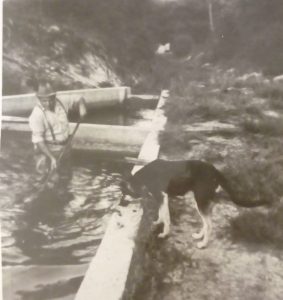

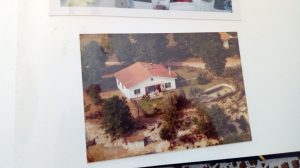

At first Aunt Regina and her husband had lived in a place called Escource, near Biscarrosse. There my three cousins grew up and went to school, mixing with water the sand of the Landes to build sandcastles in the schoolyard. With his shrewd entrepreneur spirit, uncle Antonio quickly thrived. He worked hard and soon made money. After twelve hours a day or more running his business, he would go back and work in his garden, where they grew asparagus that they then packed and sold. He made enough money to eventually buy himself a large estate in Saint-Symphorien, where he built a large family house. A stream passed through the land, and he obtained permission to divert it and build pools where he farmed trout to sell at local restaurants. My aunt served the customers, pulling out the fish with a net.

As it is often the case with migrants, uncle Antonio had come to France on his own and Aunt Regina arrived a bit later, when he was somewhat settled. She was yet unable to read or write but she managed on her own the long train journey from Pozoblanco to Hendaya, with her three daughters in tow. She had sold Uncle Antonio’s mules for a good sum of money that she brought to Bordeaux hidden in her bra. Although she would not suffer economic hardships, she would face a steep learning curve in order to adapt to her new environment. The language barrier would be the most immediate obstacle for her. Uncle Antonio learned French quickly because he was out and about all day interacting with people while he was dealing with things, but she hardly ever left home, tied as she was to taking care of the three girls.

My father, who had worked for some time with uncle Antonio in Pozoblanco, before he migrated to France, told me that he “worked like a donkey” and that they argued a lot because he was very demanding and was seemingly never pleased with the work that others did. Dad also told me that uncle Antonio was a regular in Calle Nueva, in whose taverns, according to my father, the worst of the town met. There he picked up those workers who were idle and in need of a bob or two, often because they had been blacklisted by the political regime, preventing access to many jobs to those who did not have the necessary political and social clean record. Uncle´s willingness to take them on was commendable and a act of mild defiance to the authorities that he so despised even if he eventually would win them over with all sorts of bribes once money began to come his way.

He was a strong character, with great self-sufficiency. He had the despotic quality of people who work a lot and expect others to work equally hard. He drank hard and worked hard. He was both irritable and charming in equal parts. If he saw anyone in need, he would go out of his way to help them. Everyone in Pozoblanco knew him, just like they would later in Saint-Symphorien, where he would become king of the place. Aunt Regina must have had her ups and downs with him on more than one occasion. For example, the day that he was drunk at the wheel and skidded off the road on a bridge. Fortunately, he got out unharmed, but he just left the car there and walked himself home to sleep it off, leaving the car in the middle of the road. When the police came to question him, he was furious and threw them out of the house. If they did not arrest him, it was only because he knew how to feather the authority´s nest. I remember him from the occasions when the family came to visit us in Barcelona driving a magnificent Citroën DS, the “shark” as it was called in Spain because its shape resembled somehow that fish. I was very proud of them and I recall how I would boast in school imbued with reflected glory: “my uncle owns a Shark.”

The engagement of Aunt Regina and Uncle Antonio was not all plain sailing. My grandfather Manuel was not impressed by his reputation as a fun-loving, hard-drinking playboy, a regular of the gambling dens in Calle Nueva, so he was against the engagement. However, as he had already rejected a previous suitor she had had, this time she fought harder to impose her will.

That previous boyfriend was called Alejandro. He was a boy that was studying for his baccalaureate. He belonged to a social class far superior to that of my family, who were peasants of little learning. Grandfather Manuel had obtained the position of santero or warden of the shrine of the Virgen de Luna, Our Lady of the Moon, the patron saint of Pozoblanco, which is about ten kilometres from the town. They had been living there since the end of the Civil War. They were eight siblings, six of them beautiful young girls in the first bloom of youth. On Sunday afternoons, they made bucolic country parties that seem to come out of the Spanish eclogues of the 17th century. A young shepherd played the guitar, and everyone danced to his tunes, celebrating their day off work. Little by little the word spread about and young people from all the nearby farmhouses gathered there for a bit of relaxation.

Among them was this Alejandro, who fell in love with Aunt Regina, like Don Quixote with his Dulcinea. He lived in Villanueva de Córdoba, a sister town of Pozoblanco. Grandfather Manuel thought the liaison was doomed as he knew that the boy´s parents would never approve of that unequal romance. Therefore, he feared that his daughter would end up being humiliated, bringing shame to the whole family.

Banned from joining those Sunday parties, the young student wrote my aunt heartfelt love letters that, as she was illiterate at the time, were read to her by Dionisia, a friend, who also wrote the answers that my aunt dictated. To avoid suspicions, Aunt Josefa, who was then very young, acted as a go-between, taking the letters to the station at La Jara, between Villanueva and Pozoblanco, from where she dispatched them to Alejandro so that Grandpa Manuel would not intercept them. Aunt Josefa, who was only nine years old, ran excitedly, cross country, feeling important for being entrusted with the secret love affairs of her elder sister. When she returned with a new letter, all the sisters were curious, but she dismissed them with mocking insolence saying that it was not a thing for little girls to know about.

Alejandro Buenestado Luna was a sensitive handsome boy. His letters were written with an old-fashioned lyrical affectation that dazzled and made my aunt swoon. The relationship ended abruptly and cruelly when Dionisia, who was jealous and a bit of a brute, decided to play a trick on aunt Regina. She sent him a letter full of such vulgar procacities that the poor boy was horrified and decided to end the romantic relationship unceremoniously. After a few days, he replied in his usual flowery style: “I took you for a rose, and you were but a dirty wench.” He never appeared again at the sunday parties, nor did aunt Regina ever see him again.

However, she has never forgotten that first love of hers and even now, at the age of ninety, still remembers him with affection and resigned nostalgia. About ten years ago, while on holidays in Pozoblanco with two of her daughters and aunt Josefa, she insisted on going to Villanueva and once there casually led them as if on a sudden whim to the street where Alejandro Buenestado Luna had lived. But the trick didn´t go unnoticed to her sister, who gently mocked her for that hopeless pining for a long-gone flame, a sweet moment of complicity between the two sisters and a painful reminder of how the wounds of love persist in time, never quite healing.

Uncle Antonio had always wanted to join his brother Boni in France, for he was very unhappy living under the disastrous and repressive regime of General Franco, which had murdered his entire family. He had tried to cross the border clandestinely earlier on, but the adventure had ended very badly. At that time, he was already dating Aunt Regina, with the opposition of her father. With that protective instinct that parents often have, he sensed that under uncle Antonio´s fun-loving bonhomie there lurked a certain insensitivity towards the feelings of others. Antonio would prove him right by the way in which he planned that disastrous first attempt to cross into France.

He had been born in 1923, the son of a widower and the younger of six boys, two of whom had been killed in the war. As we know, his brother Boni had moved to France after the fall of Barcelona. Another one, Miguel, had joined the maquis (resistance) after Franco´s victory but he soon tired of that doomed Quixotic enterprise. Hoping that the authorities would be lenient with him, for he had not committed any blood crime, he returned to town, where he was quickly seized by the Civil Guard and thrown into jail never to be seen again. The same fate befell his brother Ángel, who was picked up by the Civil Guard while labouring in the fields and no one ever knew more of him either. Uncle Antonio only survived because he had been too young.

Therefore, his determination to flee from Spain as soon as he was old enough to do so is understandable. What is perhaps less forgivable is that he planned his escape without telling aunt Regina, who only found out about it when news came to town that her boyfriend, whom she thought was on a business trip in the Ciudad Real province, had been arrested in Irún and was imprisoned in San Sebastián.

She felt humiliated and vowed not to see him ever again, although later, when he was released after serving a three-year sentence in Córdoba´s prison, the relationship resumed. The ways of love are as inscrutable as those of divine providence and if anyone claims never to forgive the misdemeanours of a lover it is probably because they have never truly loved. Uncle Antonio, besides being a skillful businessman, was clearly a consummate seducer too.

Aunt Regina had been informed of Uncle Antonio’s misfortune by a sergeant of the Civil Guard called Miguel, who was also after her. He broke the news to her with relish, savouring his triumph: “Where did you say your boyfriend was?”, he asked her. She replied that he was on business in La Mancha. It was then that he broke the news to her that he had been arrested while trying to cross into France along with a man and a woman, both also from Pozoblanco. These were a cousin of his and a woman whose husband had also been in France since the fall of Barcelona, like Uncle Boni. They released her but he was imprisoned for three years, first in San Sebastián and then in Córdoba.

Feeling that she had been played for a fool, aunt Regina broke her engagement. Thinking that she was fair game then, the sergeant tried to seduce her. She was flattered and not entirely immune to the man´s charm, what with his handsome looks in uniform, his rifle and all the accoutrements of a guard. He also knew how to win her over, vulnerable as she was then. One day, he tricked her into a fabric store on the excuse that he wanted advice on the best cloth to cut a suit. She refused at first because it did not seem appropriate for her to be seen with a man who was not her boyfriend, but eventually threw caution to the wind and accompanied him to the textiles shop. Once in the store he managed to convince her to accept a fabric to make herself a dress.

But his seduction strategy would prove useless, because in the end my aunt returned to charismatic uncle Antonio when he got out of the Córdoba prison. To add insult to injury, with the fabric that the sergeant had bought her, aunt Regina would eventually make her wedding trousseau and cut a birth dress for her firstborn, my cousin Mercedes.

I remember my first visit to the family in France in 1976. My father took us in his car, a Renault 4L, and my cousin Manuel, son of my aunt Nicasia, came as a co-pilot to help him navigate the roads of the neighbouring country, dealing with any exchange with the natives, for he spoke quite good French.

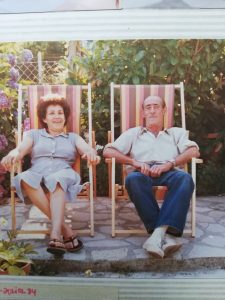

We had a great time and I will never thank my uncle Miguel and my aunt Josefa enough for having taken us so generously and with such great affection. We visited my aunt Regina’s family in Saint-Symphorien but stayed for almost a month in Saint Médard-en-Jalles, at aunt Josefa´s. We must have caused great disruption to the family routine, but I don’t recall any sign of weariness. On the contrary, they welcomed us with great naturalness, delighted to share their life with us during those weeks that have stayed with me as the image of the perfect summer holidays.

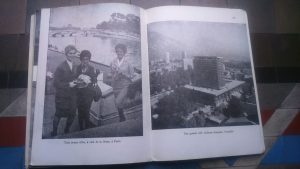

By then Aunt Josefa and Uncle Miguel were already very well settled and my cousins perfectly “frenchified”. My aunt, who worked as a cleaner, had become very close with one of the ladies she worked for. She was a university professor who studied Spanish and suggested organizing an exchange group in which they spoke in Spanish and French, so that aunt Josefa would improve her adopted country’s language and the others their Spanish, learning the colloquial and idiomatic language that is so different from the abstraction that is usually taught in language courses. The group was very successful, and they ended up organizing snacks and visits to cultural activities in Bordeaux, which contributed to making my aunt feel comfortable in her adopted country. Despite his initial reluctance, uncle Miguel also adapted well in the end. He learned French, although with a very idiomatic pronunciation that was the delight of the family, who still remember fondly how he said “c´est sartén” (frying pan in Spanish) for the correct “c´est certain”. I remember him playing “boules” and drinking Ricard in bars, like a native. My cousin Jeanine had finished high school and was wondering whether to study advertising drawing in Paris or Barcelona, where she finally decided to go. Cousin Virginie was about ten then, and cousin Manuel must have been sixteen.

Shortly after our visit, Manuel would have his own tragic encounter with history. He had a friend, Hervé, who sparked my budding homosexual desire. Neither of them was a good student. They smoked Gitanes all day and took on the air of “jeunes ennuyeux”, although they were in fact just a couple of provincial boys who liked to dream themselves big. The two spoke of dropping out and enlisting as volunteers in the army before being called to do military service, then compulsory in France. Both Manuel and Hervé were thinking of choosing an exotic destination in one of the French overseas departments, imagining a life of glamour in a warm place like Tahiti or Martinique, surrounded by exotic women under the sun of the tropics and swimming among coral reefs.

Unfortunately, none of them would realise that dream of exoticism and easy life. They both died young, Hervé of causes that we do not know, and Manuel of an agonizing disease that he developed while in Djibouti, a small French colony in the Horn of Africa where he was sent when he was called to do military service. In the event, he did not volunteer but was conscripted in the regular army in 1979.

In 1977, after a referendum, that old French outpost had declared itself totally independent. It had played a strategic role since the opening of the Suez Canal, but the times had changed, and the old colonial past was quickly morphing into something else. However, France continued to have a military presence and hence my cousin was serving there.

He remained in service for a year. He was discharged in 1980 and returned to France already seriously ill, suffering from a very debilitating condition. He lost weight until practically becoming a skeleton. He spent two years in and out of hospitals, slowly withering, until he died on August 4, 1982. The sadness caused by his death weighs heavily in everyone’s heart, just as the memory of that ill-fated Hervé has stayed with me, my own version of that indelible track that one first love leaves in us, even if in my case, being still so young, it was only the awakening in me of a vague desire.

I remember the chapter in my history book at school dedicated to the Modern Age. It was illustrated by Delacroix’s famous painting, “Liberty Leading the People.” It shows a personification of the French Republic as a woman with one breast exposed raising the tricolour flag. For me, as for so many other Spaniards raised under Franco´s dictatorship, that was what France meant: a sanctuary of freedom, a place to escape to breathe if Spain suffocated you.

That summer of 1976 was for me one of those unforgettable summers that mark the passage from childhood into adolescence. Julian Clerc, Dalida and Claude François were playing on French radio. It was also the year in which the Spanish filmmaker Carlos Saura had won the “Palme d´Or” at Cannes Film Festival with his film “Cría Cuervos”, and the song that appeared in it, “¿Por qué te vas?”, was also heard at all hours on the radio. For us Spaniards, suffering from an inferiority complex due to the dictatorship´s backwards ways in those progressive times, it was a source of pride. I also remember a very catchy song that was on a lot that year and that my cousin Virginie hummed: “La ballade des gens heureux”, which was sung by Georges Lenorman. It has stuck in my mind with that persistence that pop songs have to bring back memories of happy childhood times, before time irrupted in life with its freezing wind of destruction.

In 2014 we had a great family gathering in Saint Symphorien, in the great café of the Centre Ouvrier Associatif, the headquarters of the resin workers union, a pleasant and comfortable place, with old marble tables and a large wooden bar, a splendid place, with that name of solid republican resonance, the perfect setting for our great celebration of family unity. There we all dined and danced until dawn. Aunt Josefa, despite all the sorrows she has been through, became the star of the evening with her “joie de vivre”. She dressed up as a witch and teased us all by throwing wads of fake five-hundred-euro bills that she’d found in a joke shop. Family members travelled from Barcelona, Pozoblanco, Paris and London. There we toasted to that Europe that the family had contributed to build with their hard work, many sorrows and much suffering, but above all with great hope and a love for the culture that they found wherever they made themselves a home.

The next morning, Monsieur Pierrot, the manager of the Cercle, a man with a moustache like a character from Asterix the Gaul, proudly showed us the tribute they had paid in 2009 to the Spanish exiles that had settled in the town, many of whom joined the Resistance during the Nazi occupation. The then mayor of Saint-Symphorien, Guy Dupiol, was himself the son of Spanish refugee fighters.

The Germans had established two ammunition depots near the town. The most important one was in a place called Jouhanet and the second in Martchand. Both were under the responsibility of a unit stationed at La Burthe. In the confusion of the last days of the war, the general in command of the region had ordered his troops to blow up those arms depots, but the resistance maquis rushed to take it, thus preventing the destruction of the entire town had the explosion gone off. Two of these brave men were refugees from the Spanish Civil War.

At the tribute paid to them at the Cercle in 2009, my cousin Pepa brought a Spanish Republican flag, but the mayor refused to fly it because the Spanish consul was to attend, and he did not deem it appropriate. My cousin, whose paternal family had suffered so much from the cruelty of Franco´s Spain, decided not to attend the event as a personal protest.

I can’t think of a better place to celebrate our reunion than that Cercle Ouvrier Associatif in St Symphorien, there in the middle of the Landes region, where a section of our family ended up taking deep roots, after escaping the poverty and brutality of post-war Francoist Andalusia.