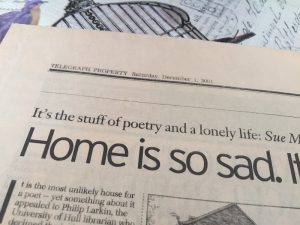

Looking for Mr Larkin

Number 105 Newland Avenue, Kingston-Upon-Hull is the last address of English poet Philip Larkin. It is in a pleasant and beautifully appointed neighbourhood of big old houses, though his is not as grand as some of its neighbours. Unusually, there is a terrace on the first floor and on it a plaque informing us of its one famous resident. There is also the figure of a toad, a reference to one of his most celebrated poems, in which he uses the amphibian creature as a metaphor for the dreary daily-grind work that we would all happily escape. It is one of the thirty odd ones made to commemorate the anniversary of his death, and which have acquired great value as time has gone by.

As I found myself recently in that city in the North-East of England, I decided to go and do my fan duties. I was there taking pictures of the place, when the iron gates start to open slowly on their own accord, as if inviting me into a magic world. I felt a bit like Alice in Wonderland but quickly dismissed the idea that they might be opening to welcome me. I saw a car parked on one side of the house, so I just thought that someone must be driving out. But a voice suddenly talked through the intercom: “hello, hello?” I heard. The feeling of magic intensified as that disembodied voice was clearly addressing itself to me. I wondered if I may inadvertently have pressed the bell while bending over to get a good picture of the house front, with its commemorative plaque and toad, so I hesitatingly expressed an apology: “Sorry, did I ring the bell by mistake? I didn´t mean to”.

“Who´s that”, says the voice. “I am a Philip Larkin fan” I reply. “I was just taking some pictures of the house. My apologies if I have disturbed you”. The voice is that of a woman and it sounds rather posh. “What´s your name and where are you from?” she asks, having probably noticed my foreign accent. “My name is Rafael and I am from Barcelona”. “I am Mrs Porter”, says the voice. Could you come in an hour?”

I am very surprised at the invitation. “Yes, sure, but I wouldn´t want to disturb you”. “It´s no problem at all”, she answers, “Come in an hour and I´ll show you the garden”. I accept, of course, not quite believing my luck that I am going to be invited into the great man´s house.

After wandering for an hour around the area, I come back and ring her bell. As the gate opens again, Mrs Porter herself comes out to greet me. To my great surprise, she turns out to be not the white middle class woman that I had expected from her voice, but a wonderfully exotic lady of dark features and striking beauty, dressed in colourful African garb. Things get more interesting by the minute, I say to myself, as she invites me into the house, which is exquisitely decorated, containing two grand pianos and lovely furniture. It is bigger than it looks from the outside, with a great glass wall running the length of the house in the back, opening to the splendid garden that Mrs Porter has invited me to see. She tells me she has made great alterations to the original, which she bought in 2002, soon after the death of Monica Jones, Larkin´s long-term lover, with whom he had a complicated relationship, as he also had a third lover, Maeve Brennan, the three of them entangled in a love triangle that has given much to speculate since, to biographers and academics alike.

“Gosh, look at you”, I say, excitedly. “Not quite what I thought Mrs Porter would be!” “What was that then?” she asks. “Well, a white middle class lady in pearls and twin set”. She laughs heartily. “What ethnic mix you think I am? Have a guess”. I take a good look at her, splendid in her African bright yellow dress with some deep blue print. For some reason, Ethiopia comes to my mind. She says no, but her eyes tell me that I have been somewhat close, so I cross the Gulf of Aden and venture Yemen, at which she opens her eyes wide and wonders how the hell did I guess. I confess I am amazed myself. We look at each other, like two teenager misfits who have met in the school yard and feel an instant rapport.

“Ok”, she says, “That´s one of my origins. Now, what´s the other one. Can you guess that?” I say Indonesia first, but she tells me is a non-Muslim country. Something in her reminds me of my friend Krishna, who was born in the Caribbean out of Indian stock so I suggest Trinidad or any other Antillean island, at which she is left speechless. She clearly thinks now that I am a Spanish gypsy seer, able to read people´s souls. “I can´t believe this”, she screams. “You are incredible. It´s Jamaica!” I just smile at her and give her a hug, feeling as overwhelmed as she is by my sudden clairvoyance.

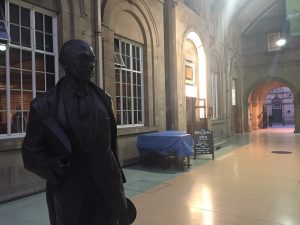

She takes me then on a tour of the house, pointing at several art-works related to Larkin that she has collected through the years. There is a miniature bronze copy of the large sculpture of Larkin that welcomes travellers arriving in Hull station, as well as a painting of a Parisian street by some friend of the poet. Miriam says that the figure of a man looking out of the window of a hotel, is meant to represent Larking himself. The picture is by a friend of the poet.

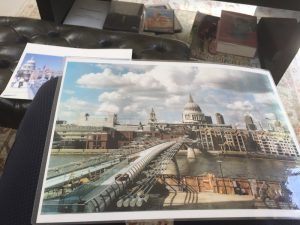

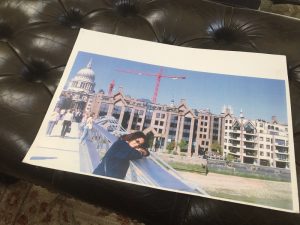

What used to be the garage, Miriam has turned into a large second living-room facing the front garden. Laying on a big table, there are some enlarged poster-size photographs of the view of the Millennium Bridge from Bankside across the Thames, with St Paul´s magnificent dome lording it over the skies of the City of London.

I point out at the brick building of City of London School for Boys and tell Miriam that I worked there for twelve years, teaching Spanish. She again opens wide those large exotic eyes of hers. “You must be joking. You didn´t, did you?” she says in utter disbelief, “But I lived here for almost twenty years”. She says, as she points herself to a plush apartment building which I know well, for it was just two blocks from my old school, next to what used to be the Swiss Bank.

So many coincidences are beginning to make me feel dizzy. I find it so unlikely that Miriam and I should have been crossing paths for so many years in the City of London only to finally meet in this quiet street lost in remote Hull. It seems as if we were destined or something. “That was the staff room”, I tell her, signalling the balcony next to the Millennium Bridge overlooking the Thames. We seem to be two kids playing with a toy model of the mighty City of London. “We were allowed to smoke there. That was long before they built the bridge and the old Bankside power station became Tate Modern”. “I know”, she says. “I lived there back then too. So you were one of those naughty teachers giving bad example to your pupils?”. “Well”, I reply, “It beat smoking behind the bike shed”. She laughs again and we proceed with the visit.

She takes me to a small toilet where Larkin is said to have collapsed the day he died. He had a stroke and hit his head against the radiator, famously crying “hot, hot!” at which Monica Jones came to his rescue, but found that she could not open the door, blocked by the body of the ailing poet. Emergency services were called and they had to break the door with an axe, so they could take him in an ambulance to the Royal Infirmary, where he was to die. Miriam tells me that downstairs toilet id the only thing in the house she has not dared to change. “Aren´t you spooked to do your business in the place where the great man died?” I cheekily ask, urging her to take a picture of me sitting on it. “I use the upstairs one, and he died in hospital anyway. You are a very naughty boy!” she shouts, but she goes along and takes the picture with a big smile. “I can´t believe I am doing this”, she says.

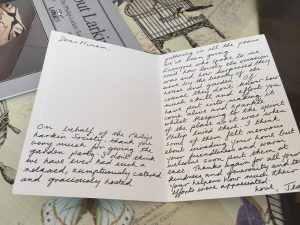

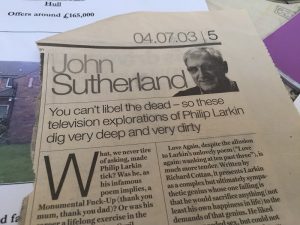

She offers tea and we sit down at the table overlooking the garden. Miriam goes in search of a file where she keeps documents, newspaper clips and other stuff related to Larkin and the house. She spreads them on the table and I quickly skim through them, fascinated. There are pictures, letters, old issues of the Philip Larkin society magazine, of which she is an honorary member, and pictures of the annual garden party she holds for them. There´s a letter from Andrew Motion, the old poet Laureate and a friend and biographer of Larkin´s, who has written to Miriam to ask if they could come and film an interview in the house for Sky TV. Miriam is quite thrilled by all, as anyone would be.

I ask her about how she came to buy the house. Was she already a Larkin fan? Did she know it was his? Had she paid extra for it? She says no, she didn´t. She just found the place through an estate agent who did not even know that it had belonged to Larkin, which is not so surprising if you think that he died in 1984 and it was Monica who had lived there on her own, largely forgotten, for eighteen years afterwards.

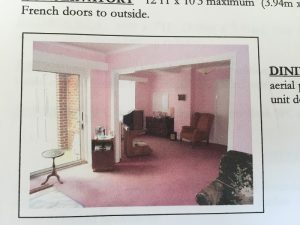

It was a friend of Miriam´s that told her about the house connection to the poet, once she had already put an offer on it. Miriam told then the estate agent, who cheekily wanted to put the price up once he knew. She shows me the original prospectus of the house sale and it doesn´t look anything like it does now. Philip Larkin was never too pleased with owning the place and famously called it “the ugliest in Hull”, which may have been a bit of an exaggeration, but it certainly looked a tired place when Miriam bought it, most definitely “in search of modernisation”, as estate agent’s blurb say.

In-between bits and pieces on Larkin´s life and work, we exchange information on each other´s lives too. Miriam tells me she is a local girl whose father was a merchant sailor from Yemen. He married her mother, who was of Jamaican origins. This brings to my mind the play “A taste of Honey”, where similarly disparate people find themselves drifting in Liverpool, a black sailor who leaves pregnant a local girl. She tells me she has suffered a lot of casual and not so casual racism in her life. I tell her I am an Andalusian who grew up in Barcelona and came to London in search of literature and adventure, escaping from what I perceived to be the ordinariness of my life. Here in England I feel free from the tyranny of ancestry, allowing me to become whatever I wish to be.

Miriam nods. She knows how I feel. She tells me her mother died when she was a child and, as her father´s job did not allow him to take care of her, she was put into an orphanage not too far from where we are, now turned into flats, of which she now owns one. Apparently, the orphanage was not the terrible place they are cracked to be in books and films, but there was no love involved in it and no expectation from the girls either. Her father came to visit her whenever he came back from his long voyages across the seas. Miriam grew up and married a local boy with whom she eventually moved to London, where he made it good as a stock-broker in the City, hence the riverside flat and the splendour of the house we are in. They are separated now and I perceive a kind of sadness in her tone as she mentions that, so we return to Philp Larkin. I take my book of poems and read for her “Days”, the poem that concludes that “days are to be happy in”, which cheers her up.

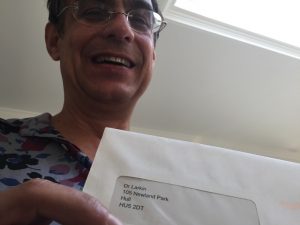

“I´ll tell you what I have got and can give you”, she says all of a sudden, going to a kitchen cupboard and producing a set of identical envelopes all addressed to Dr Larkin, 105 Newland Park, Hull. There are fifteen of them, one for each year since she has lived at that house. They are all still unsealed. Miriam says she receives one every year but has never opened them. She gives me one as a souvenir on condition that I should never open it either. I am mighty honoured and thrilled at the privilege and I gratefully kiss her.

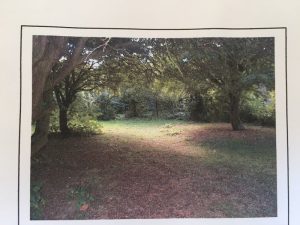

“Worry not, darling”, I say to her. “I am gay and married to a wonderful man, in case you fear I am a gold-digger, intent on seducing you out of your money”. She laughs heartily. “Now I never. You don´t say!” We both laugh and hug. Then she takes me by the hand out into the famously large garden, of which Larkin moaned he did not know what to do with and just kept as a dull extension of lawn with a few trees at the back, as it is shown in the prospectus for the sale of the house which I have just seen. Apparently, Monica Jones found no use for it either.

Oh, but what a different place it is now, thanks to Miriam´s tender loving care. This woman surely has the power of life at her fingertips. We walk around, admiring the magnificent plants that she has grown since she moved in, going around the different secluded corners where guests can sit in little groups. There are mirrors in the back to give a trompe d´oeil impression of it being double the size that it is. There are also beautiful, slightly surreal ornaments, such as chandeliers dangling from trees. The pièce-de-resistance, however, is a fountain commemorating the visit of Queen Elizabeth.

“Don´t tell me the Queen herself has come to your Larkin´s parties”, I say. “It does not seem to be her kind of thing at all, is it?”. It wasn´t the present Queen but her mother, and it wasn´t Miriam´s present house that the old queen Mother visited in her day, but the orphanage where Miriam grew up. She was still a child and thrilled to meet the great lady –a real queen!- as any girl would be. Years later, when the orphanage closed and they sold in auction all its contents, including that commemorative fountain, Miriam bid for it and won it. She also put a bid for the benches that were at the institution´s large grounds and which now are scattered around old Philip Larkin´s house, complete with the little metal plaques that say in memory of whom the bench was made. This is so touching that I am almost moved to tears. Miriam is soul of kindness and one of the women with the bigger hearts that I have ever come across.

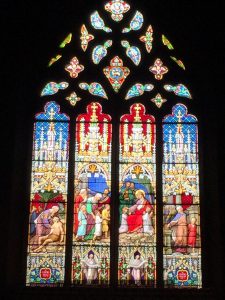

After our walk in the garden, she suggests that we drive to the Cottingham graveyard where Larkin, Monica Jones and his other lover, Maeve Brennan are all buried. I protest that I would not want to impose it on her, but she seems quite pleased and willing to do it for herself, never mind me, so I gladly go along with it. We board her big comfortable car, a Chelsea tractor, as these SUV vehicles are mockingly called in London. Before visiting the cemetery, we enter the parish church, which dates from the twelfth century. As we wander around, I remember “Church going”, Larkin´s poem: “Once I am sure there’s nothing going on / I step inside, letting the door thud shut. / Another church: matting, seats, and stone, And little books…” I share with Miriam how much I identify with what he expressed in that poem: the need for the sacred, once we have stopped believing in God, but she tells me that she does very much still believe, that as matter of fact, she has recently converted to Christianity herself, a conversion that I find greatly becomes her, for she is all light and sisterly love.

We wander then to the graveyard, where I soon spot Larkin´s grave, bearing the simple inscription: “Philip Larkin, writer”. A few rows of graves behind there is Monica Jones´s own final resting place. Not far, the third in discord, Maeve Brennan, the nice girl from an affluent catholic background who Larkin managed to bed despite her rigorous religious beliefs. It took us a while to find her grave. Miriam had to use her mobile phone to call Maeve´s brother, who is her son´s piano teacher and she knows well. Between his instructions and a photo of her grave we searched in Google, we finally find it. It bears a famous quote from Larkin´s beautiful poem, “The Arundel tomb”: “What will survive of us is love”.

Next to the grave there is one of those benches people pay for to remember their loved departed ones, like those that Miriam salvaged from the wreck of her old orphanage. In its memorial plaque, we read again those two famous verses from the Arundel Tomb.

Miriam and I sit silently for a bit thinking of all that is left of the sound of fury that was their lives, that is anyone´s life. It is sobering to see those three buried there, some distance from each other, together and apart, as they always were, as perhaps all of us are. Their uneasy but by no means unusual love triangle now continued through other people´s projection on them. Now that the three of them have long gone, they have become all of us, as year after year new TV programmes, biographies and whatnot argue and counterargue about who did what with whom and who betrayed the others the most. Famous writers who vaguely knew them in their day, express their opinions unrestrained, now that they know the incumbent ones can´t reply to any inexactitude. Monica is commonly depicted as an unpleasant lady, and so is Larkin made to be, whilst Maeve seems to tick everyone boxes and she is thought a saintly woman, who sacrificed her believes for love. The truth, one suspects reading this and that, was surely more complex that all that. There are no winners or losers, just humans ever trying to live their life the best way they can.

We board the car again and leave the dead to themselves. Miriam drives me into town, to a penthouse apartment she owns in the highest building in town. It has magnificent views of the whole city at its feet, the Humber beyond and Lincolnshire in the distance. “Did you ever take the old ferry, before the suspension bridge was built?” I ask Miriam. She nods.

The once mighty Tattershall Castle, is now a restaurant moored in the Thames, near Charing Cross Bridge. We perch out from that high point and then she drives me back to my lodgings at the Whittington & Cat, a Victorian pub near the old docks, miraculously surviving amid a wasteland of retail parks, ring roads and car parks, remnants of the ill-conceived modernisation of the place in the late sixties, when urban planners expected a future that, as usual turned out to be quite different from what anyone expected.

Miriam and I kiss and hug. She gives me her card. I promise to write. The following morning, I board the train back to London and check the address on the back of the envelope that Miriam gave me. A quick google search takes me to an industrial park in the outskirts of Manchester where a company selling hearing-aid has its headquarters. They have recently been bought by an Italian multinational. They obviously, don´t care or know who Dr Larkin was. Better not too open that envelop, I think. Its content is what matters less. Its magic lies, as Miriam well knows, in receiving the envelopes year in year out, prolonging life beyond the grave, allowing us to imagine and recreate.

This is the text I have put together for her, in memory of an unforgettable afternoon in Kingston-Upon-Hull. One never knows where one´s quest is going to lead. The important thing is what one collects on the way as one searches and explore, the object is just the excuse, whether it is the Holy Grail or Mr Larkin. We will all become one day just a name and an address on an envelope nobody opens but one thing is clear to me: Dr Larkin was right, what will survive of us is whatever love we may be able to give as we plough along the path of life.