Men at War

This story started in spring 2015, when I first met Sarah Forman at a party in Cambridgeshire. I told her about my plan for this site and she invited me to see a collection of pictures left by her late husband, Patrick, who had died the previous year. He was a keen amateur photographer and I was welcomed to see if I could get inspired to write something about those images, for it would be a shame that his work would eventually end dispersed here and there. I agreed and so, a few weeks later, we arranged tea at her place to have a look at that archive and put together the story they had to tell.

So, on a bright afternoon, I found myself in Sarah’s cosy terrace house, surrounded by Patrick´s law books, his grand piano and those significant objets d’art we all collect as we go through life. We ate Sarah’s homemade cake and looked at Patrick’s life spread in front of us, pieces of a puzzle that we were going to try to fit into place. I asked questions and listened to Sarah’s recollections as well as stories that she only knew second-hand, for many of the photographs dated from a time long before they met.

Patrick Forman was born in 1923 in Moffat, Scotland, he was educated at Loretto School in Edinburgh, and he would later graduate from Pembroke College, Cambridge. He qualified as a solicitor and developed a talent for photography. When the Second World War broke out in 1939, he joined in the RAF hoping to train to fly Spitfires, but was instead commissioned into the field artillery. He was invalided out of service when he was struck by tuberculosis of the spine and spent the rest of the war at St Thomas Hospital, just across from the houses of Parliament.

But he never gave up on his dream of flying and, later in life, he acquired a private flying licence and his own little plane. He would eventually write a book on airplane safety that helped to introduce many of the measures now standard in commercial aircrafts. He made a significant contribution to safer flying, both through his reports as The Sunday Times air correspondent and through his book Flying into Danger. It was while working at The Times, for which he was also legal correspondent, that he met Sarah, then working as a feature’s writer for the paper’s Sunday magazine.

Flying was the way he found to introduce himself and make inroads into Sarah’s heart. He approached her one day at work, while they were both rummaging through the letters and messages left at their pigeonholes. He had somehow heard that she had a small house somewhere in France, where she often escaped to paint, and suggested to fly her there one weekend in his own little Cherokee plane. Well, how could an offer like that be refused? So, they did and went on to fall in love and eventually marry in 1970. They kept working for The Times until the late eighties, when the paper was taken by Rupert Murdoch whose aggressive managerial style was not to their taste, so they decided it was time to go, leave that brave new world to the young.

They had lived first in London but then moved to that little terrace house a stone throw from Cambridge station and commuted together daily to King’s Cross. British Rail had just launched a breakfast service, and that was a small luxury they enjoyed. They would live happily for decades, until illness hit them. First Patrick had succumbed to it, then Sarah was diagnosed with myeloma, a cancer of plasma cells, for which she was being successfully treated at Cambridge Addenbrooke’s Hospital. We got on very well. I liked her joie de vivre, her stoicism and grace, that ordinary bravery that often goes unsung.

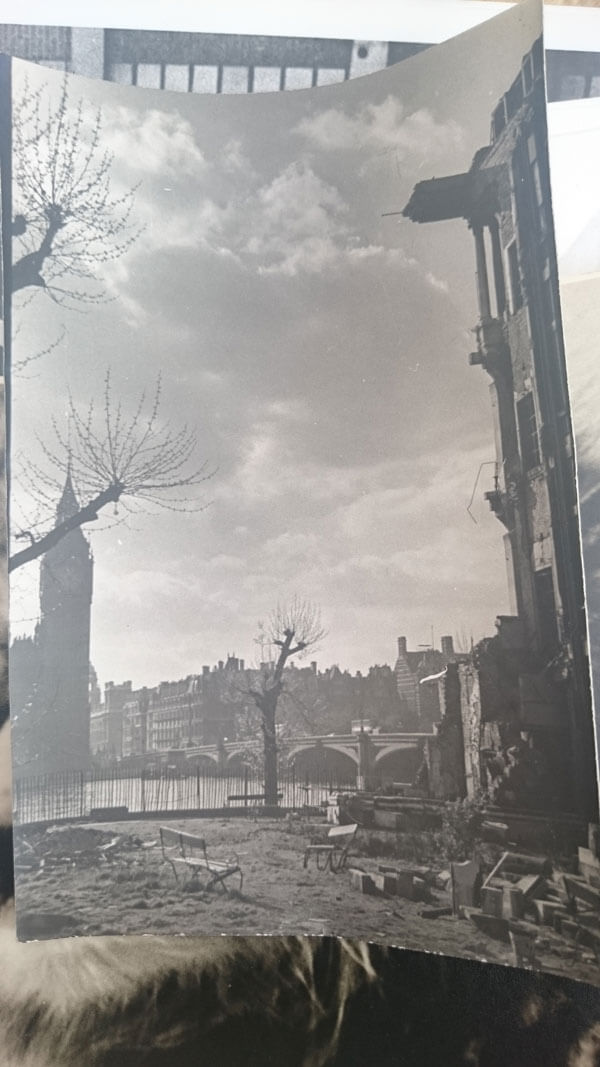

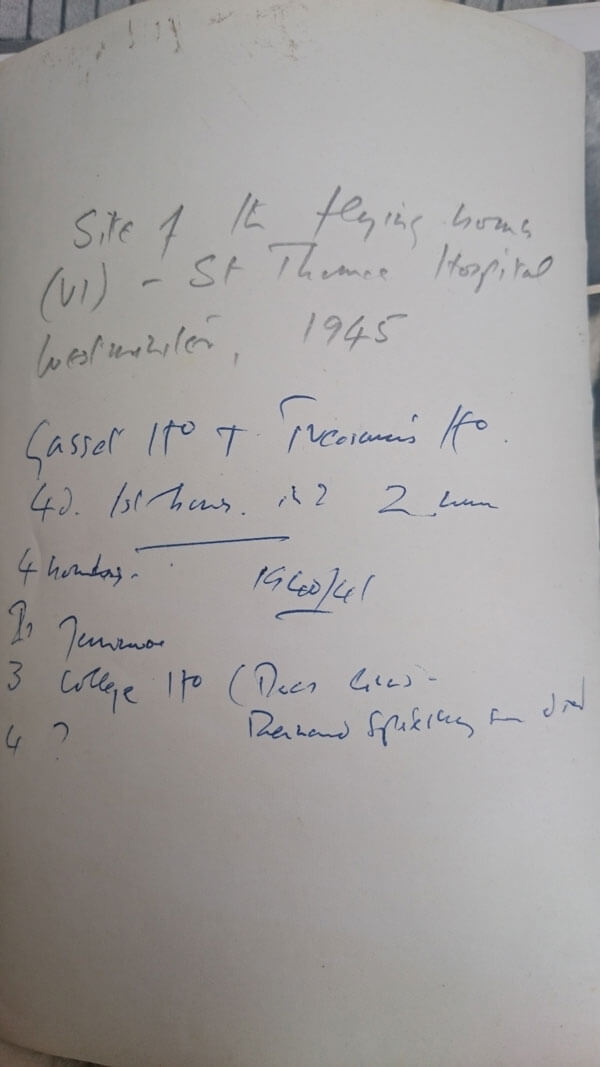

In 1944, the last year of the war, Patrick was admitted to Saint Thomas Hospital, in London. He would remain there until 1946. To pass time, he smoked and took photographs of City Ward, where he was a resident. He was an acute observer of the daily life there. They are not posed or staged photos, but snapshots that have a pictorial quality, offering us a window into that long gone world. Patrick shows a keen eye for framing and to capture life as it unfolded in front of him, almost cinematographically. In his self-portraits, he looks patiently resigned. We see him inspecting with good old English phlegm the damage caused by a flying bomb that hit one of the wings of the hospital.

Those were the precursors to contemporary cruise missiles, the last tantrum of the mad Fuhrer holed up in his bunker in Berlin. His dream of a Reich that would last a thousand years -the stuff nightmares are made of- was literally collapsing on his head. He had committed the most despicable crimes, as well as the most hubristic sin. Faced with the inevitable defeat, he had reacted in the only way he knew, like an injured animal, like the failed artist that he was: killing, destroying his work, deluded till the end.

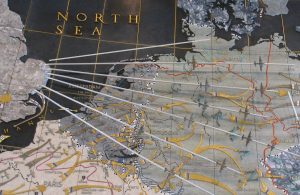

Technology had always served him well so, perverse magician that he was, still tried to pull off one last deadly trick out of his sinister top hat. In desperation, he sent the aptly named V1 and V2 missiles, the last cartridges left in what had been his well-stocked arsenal. V for vengeance not for victory. They fell over the capital for several long months between 1944 and the end of the war in May of the following year.

And there was Patrick, history intersecting with his own individual path, as history usually does, always ready to screw up people’s best laid plans. When war broke out, like many young men in Britain would do, Patrick had rushed to enlist at the glamorous RAF, attracted by the manly novelty of planes, the sexiness of uniforms and the dreamy excitement of flying over the clouds. However, his dream was not to be –not just yet, at least- for Patrick was turned down for flying because he had a stammer and someone in the high command thought he may not be able to cope with radio communications. Disappointed, but determined nonetheless to contribute to the war, he then went on to join the Scottish Borderers regiment, who sent him to a gunnery range in Norfolk where, paradoxically, he would never be too far from radio transmissions.

The Germans kept firing at them from across the North Sea. Day in day out bombs rained on their camp. But young Patrick would be undeterred. He aspired to be up in the clouds, to do his bit while experiencing the trepidation of flying high over the embattled earth. It wasn’t for him the safety of a job in the rear-guard, monitoring the air from a listening station somewhere in deepest Surrey or Huntingdonshire. He longed for the heroic din of battle, a proper “good war”, which may seem a contradiction in terms, for how can any war be “good”? But with the motherland so ruthlessly attacked, soldiers saw as their duty to get involved, to show their bravery and, hopefully, to be decorated for it, to dodge death as they confronted the enemy’s fire.

However, Patrick would soon be forced to abandon his thirst for heroic exploits. He had eventually managed to be transferred to gliders, and 13 times his platoon had been primed to be dropped over France though at the last minute they were always ordered to stand down. As good or bad luck would have it, while on a training run, Patrick crashed on landing and got injured on his back. He went on hurting for days but, as one did in wartime, he did not complain and simply, quite literally, soldiered on. The camp medics gave him painkillers and he just kept going, carrying his heavy kit bag with all the accoutrements paragliders had to take with them.

While enjoying leave in Oxford, an uncle of his who happened to be Chief Radiographer at the city’s Radcliffe Hospital suspected something was amiss with Patrick’s back. He took an X-ray of his vertebrae and discovered not only that his accident had cracked his spine but also that TB had set in on the wound. TB was then still a dangerous disease, as it was not until two years later, in 1946, that the antibiotic streptomycin would put an end to what had hitherto been a deadly scourge.

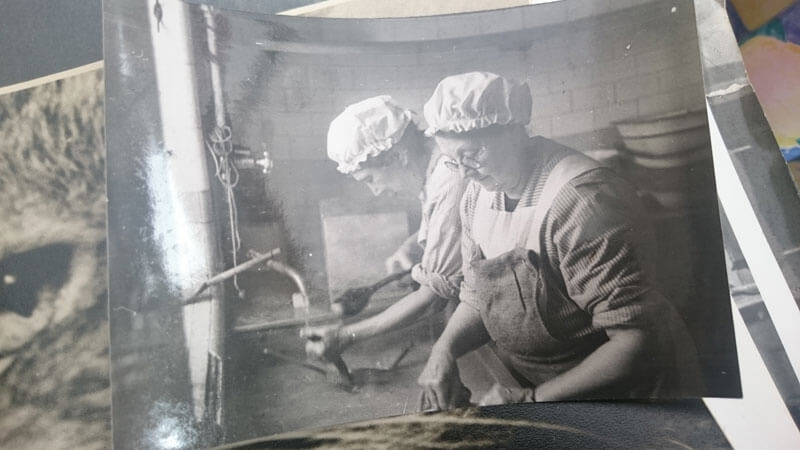

Thus, for the rest of the war, Patrick was to sit in a ward in St Thomas’ Hospital, opposite Parliament just across Westminster Bridge, under the tender loving care of Nurse Allcock, the doctors and the rest of the hospital team: the brave no-nonsense South London cooks, the chatty young girls who came to help. One pictures them distributing lunches and dinners, amiably flirting with the handsome forward tommies, who lay there injured. Young and far from home, those boys surely appreciated their good caring, their kind words and the ray of sunshine and hope that shone in the girl’s eyes. They shed for them some merry light that uplifted the homesick boys, a welcomed distraction from the ugliness of war and the frustration at having to be out of action while the war raged on.

By then, it had gone on for four years and there was one more year still to go, time enough for everybody to get used to that inferno of fire and bombs. This was a new type of war, one with no business as usual. People in London experienced the same terrors as soldiers on the front. It was a total war from which nobody was spared. The air raids made soldiers out of every citizen that came out of their front door every morning to go into work, unsure whether they’ll have a home to go back when evening came. There was a deliberate targeting of civilians to cow them into submission, demoralising them. The aim, as we would say now, was to terrorise them all. By the end of the war, about thirty thousand Londoners would have been killed by bombs.

The winter of 1944 was the coldest for many years, German attacks gave the city no reprieve. Illness was in the air, along with rumours of epidemics and mounting deaths. Just as they were unsure whether they would survive the day’s work, Londoners went to bed every night uncertain that they would be alive at sunrise.

And yet, you would be hard pressed to tell those terrors from the faces of Patrick or the team of nurses at St Thomas in the pictures he took during his days there. Regardless of the harsh sufferings and sheer privations people must have gone through in those last years of war, one looks at them and sees nothing but charm, tender loving care and deep humanity. We see nothing but duty as love, hardships endured with grace and that resilience matched with jolly camaraderie that would come to epitomise the “blitz spirit”, which in years to come, turned into a cliche, would so often be invoked by politicians as shorthand for the stoic patriotism of the British folk.

The V1 and V2 missiles kept raining down. Although Londoners had become accustomed to bombs dropped by planes, these new missiles were a cut above, causing destruction and havoc on a scale that had never been experienced before. They had much less time to run for whatever relative safety there was to be found. You heard the chilling engine tone high above and then you heard it stop, just a few seconds before it fell, dead weight, razing entire streets below. It was clear that the mad man across the sea in Berlin had managed a last deadly standoff.

One of those missiles hit St Thomas right on the spot, killed several people and injured some more, forcing the nurses to take the sick beds out into the terraces overlooking Parliament across Westminster Bridge. There is an account of that dreadful event by a nurse who was on duty that day:

“I remember being stuck above ground level, holding a jar of thermometers. If we broke a thermometer, we had to pay for it, so I was being very careful. Then I heard a Doodlebug starting to doodle above me – when the noise stopped, you knew the bomb was about to come down. When the Doodlebug hit the other end of the hospital, two policemen in pyjamas helped me to protect my thermometers and made sure they didn’t crash to the ground.”

https://www.guysandstthomas.nhs.uk/news-and-events/2015-news/september/20150810-st-thomas-nurse-remembers-London-in-the-war.aspx

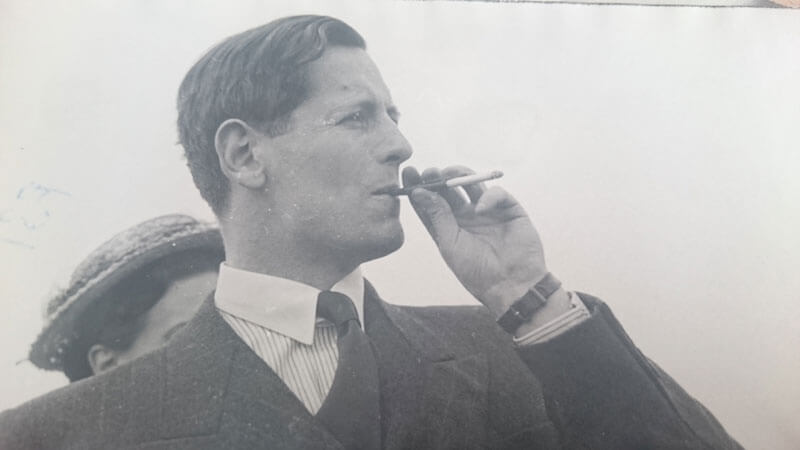

Patrick took it all in his stride, capturing with his lens what he saw, calmly puffing his cigarette through his holder, as it was fashionable then. He cuts quite a dash, and one can well imagine him being quite the darling of the place. Those were very different days from now, pets were allowed in hospitals as well as smoking, and Patrick was given a cat to keep him company. He named him “Haggis”, in honour of his Scottish homeland. There’s a beautiful picture of nurse Allcock stroking him, and another one of Haggis looking somewhat mean.

Patrick inspected and documented the extent of the damage done by the flying bomb. He took pictures of the destruction against a backdrop of Westminster Palace. The mighty bulk of Big Ben, rises seemingly untouched, blurred by the Thames fog, a poignant symbol of everything they were fighting for, strengthening the nurses resolve not to be cowed by the mad man’s tricks. They would soon be vindicated, a triumph not made of pompous words uttered in grandly staged stadium events but made of the humble caring for the weak and the sick.

Patrick’ s hospital looks a friendly and happy place. We are confronted with the smiles and the quiet determination of everybody at City Ward. Lunches are being served while one imagines remarks gallantly exchanged; cats are duly fed and played with, and children reassured. It seems the very image of that now ubiquitous motto, “keep calm and carry on”, a sign that as a matter of fact was never used during the war, discarded as it then was by those suffering the bombs, who deemed it too patronising.

People could endure suffering and pain, but they did not take kindly to being told how to do so.

Given the difficult circumstances in which they found themselves, it is a marvel the gaiety transpired by Patrick’s pictures at the hospital ward. We see Nurse Alcott playing with Haggis, the ginger tabby cat, a therapeutic pet who kept everybody’s spirits up and helped Patrick put up with the boredom and frustration at his enforced inactivity while he recovered, aware that others were fighting the good cause for him.

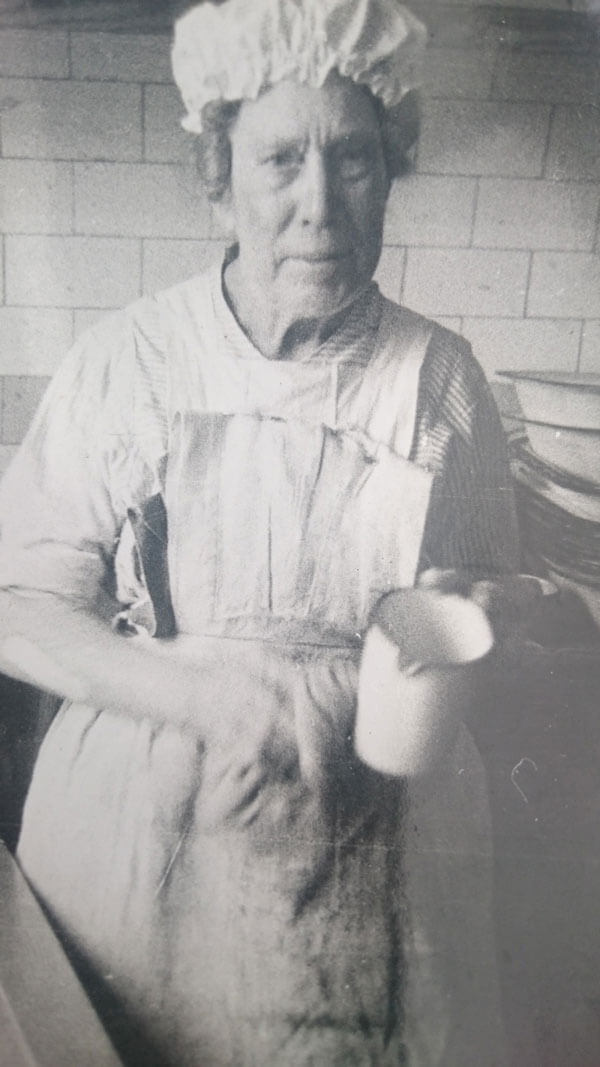

Hospitals took in wounded soldiers and civilians all day long, and the doctors and nurses were working round the clock to help as many people as possible and relieve their pain. They were certainly kept busy and put on long hours every day. And yet, there is an atmosphere of calm serenity on the face of Sister Barbara Wilson, City Ward’s night charge, and in those of the more menial staff, the ladies serving food or doing the washing up. They are, one imagines, wives and mothers from South or East London. Their husbands and sons would have been mobilised, fighting in far-flung corners of the world, in Burma or El-Alamein. They did their duty seemingly unfazed. You can see pride and compassion in those indomitable no-nonsense ladies who no doubt endured without complaint the vicissitudes of fortune, resilient and almost indifferent to either pleasure or pain. There is not a thought of defeat in them, despite the fact that they may very well find, as their shift was done, that their house had been blown up by bombs and they would have to spend the night in any of the sad halls set up all over town, where they would had an uneasy sleep before returning back to work the next day.

Patrick took in everything with his camera: the dresses of the charming nurses, their hairdos, their lipsticked smiles, as well as the austere and resolute stare of the cooks, whose eyes nonetheless betray their delight in Patrick’s debonair manners. One can almost hear his clever banter and their spirited backchat, Patrick’s clipped posh tones contrasting with their raucous south London drawls; the husky voices of the older matrons against the sweet softly-spoken young nurses. One imagines jokes exchanged and jolly remarks made, as they all went about their business, almost like a choreography in which each of them plays a role, swinging about with perfect poise, lovingly taking care of the injured men.

They look oblivious of the fact that their luck may run out at any time; that their lives may be the next in line. The mood in the ward doesn’t feel sullen or tense but, on the contrary, playful and full of zest for life. A pleasing spirit of conviviality comes out of those images. Everybody shows determination, tenacity, buoyancy even, but, above all, love and compassion for each other.

I can imagine the cooks saying their prayers as they heard the chilling whistle of the bombs flying across the sky, the Irish ones making the sign of the cross, holding their breath, thinking of their loved ones far away. They must all have gathered somewhere deemed safer in the event of a bomb hitting the place, down in the basement one should think but then, what about the seriously infirm, the bedridden, those who could not easily be moved? Nothing left but to pray for them.

And then it all stopped. At the end of March 1945, a rocket fell upon Stepney, another on Tottenham Court Road, then silence. That was all, the raids ceased; the rocket-launching sites had been taken by the advancing allied force, slowly but surely making haste to reach Berlin, trying to get there ahead of the Russian communist troops, a race that would trigger the next war, mercifully a much cooler one, in Europe at least, than the one that was just about to stop. The Battle for Britain was finally won, not just by Mr Churchill’s few but by the country’s many, who were left exhausted after five years of relentless ordeal, trying to keep alight for the world the flame of hope, as Britain had turned into a modern-day Noah’s Ark, stoically resisting the deluge that had swept across the whole Continent.

On 8 May 1945, large crowds gathered in Piccadilly and Trafalgar Square, filling the Mall to hear the king and Mr Churchill give their expected speeches. Never so many had owed so much to so few indeed, except it had not quite worked like in the end, for it had been the many who had turned to be the real heroes of that long and exhausting war, in which everyone had been a soldier and every home a front line.

Nurse Allcock, née Palmerston as Patrick wrote intriguingly behind a picture he took of her -why did it matter to him her maiden name?- and the washing ladies from Stockwell or Bethnal Green, as well as all the rest of the St Thomas’ cast must have joined the crowds that filled The Mall. They acclaimed the king and the speech the Prime Minister gave from the Ministry of Health. People took to the streets and danced and kissed celebrating victory, but the Britain they would wake up to the following day was a devastated one. Rationing would last for a decade after the war and gradually the empire would fade. A new age was about to start, a fairer society was to be built on the ruins of the old one, the aristocratic order that had led to unimaginable destruction and sufferings over two world wars.

They had won, the jubilant crowds, and were determined that all that sweat, blood and tears would not have been shed in vain. So, come the election on the 5th of July, barely a couple of months after the end of the war, it wasn’t the victorious Mr Churchill´ Tories, but Mr Attlee’s Labour who would win the day, ushering in a new world: the welfare state, free health, subsidised housing and education for all.

Patrick, privileged witness, was across the river from Westminster when the crucial election was held, and history made. He saw the significance of the event. In March 1946 he was still at Saint Thomas. It must have been a warm evening, for he asked his bed to be taken outside to the balcony overlooking the Thames. He took a picture of Parliament, where the MPs were deliberating the policies that would set the basis for Britain’s rebirth from the ashes of Empire and war to become a more cheerful and desirable place than it had hitherto been, a world that two decades on would bear fruit in pop music and an irreverence towards the upper class, of free education and health care for all, decent housing and subsidised arts; a real brave new world, far removed from the grey fogs of the past. That is what they had been fighting for, the crowds, both at home and in faraway shores.

Patrick later wrote a few notes on the back of a picture he took of Parliament that day: “I slept on the balcony of the ward overlooking Victoria Embankment. Skyline shows the old Scotland Yard Building, since demolished. The beacon on Big Ben signals that the House is sitting”. It was the Labour-controlled Parliament after the landslide victory of the previous year.”

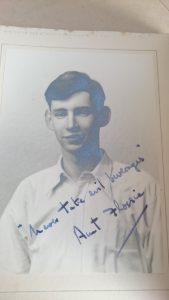

Amongst those hundreds of thousands of casualties of the war was Patrick Forman’s best friend, Alastair Hope-Robertson, a young man also from Moffat who did join the RAF and would die while flying on a mission in July 1944. A bunch of pictures of him came out from an envelope as Sarah and I went over Patrick´s archive.

I was quite taken by his beauty and the evocative power of those old black and white images that Patrick took of him. Some showed himself alone, standing bold in the full bloom of his graceful youth; in others he posed with a group of other adolescent boys. They are dressed formally in what looks like school blazer and shorts, but wear no ties, pointing out to a leisure time on a hot summer day. They look like sixth formers on their last days of school, exchanging banter and longing for long evenings of freedom in the coming summertime.

Given that they are the generation born in 1923, this would date the pictures probably in late June or early July 1939. They were thus standing on the brim of an abyss, just before the war, which adds pathos to the photographs, for we know that their leisure is not going to last, that whatever yearnings they may have had were to be abruptly cut short by the brutal war that was to be declared come September. Their future would be curtailed and their golden days, intended for love and joy, damned to battle and tears.

There´s one photo of Alastair wrapped carefully in a folded cardboard pocket on whose cover we find this note written in Patrick´s shorthand:

Killed July 1944 flying over Holland RAF Lancasters

Alastair Hope-Robertson

Photos always set in motion a train of thought in the viewer that is quite free from whatever intention the photographer had when he took the snap. These ones transported me to the world of Evelyn Waugh´s Brideshead Revisited, to the image of Charles Ryder and Sebastian Flytes, and their own foundered friendship and love. I thought of the school chapel in the background as the large house that gives name to that novel where, vacated by its occupants, Charles finds himself billeted, setting in motion his own train of memories, unleashing his own mix-emotions. A photograph uncovers meanings even when none was intended. Once taken and put in an album or, as in this case, packed inside an envelope, it is like a book or a work of art. What the artists may or may not have intended does not matter, for the work takes its own life and their interpretation left at the mercy of those who receive it. Pictures take meanings in context and in time and Patrick´s thus act as a testament of doomed youth. The smiles and casual summer insouciance of those boys becoming a valediction.

What Patrick had originally intended as snapshots to be cherished of lifetimes about to set fly, have turned into a kind of cenotaph and, as a result, for us who watch them now, many decades down the line, as an indictment of war and of the commercial and political affairs that led to wipe out an entire generation of young men, sacrificed before they could start their lives. Alastair would die at the age of just twenty-one, when his bomber plane was brought down as he flew over Holland on a mission to bomb the city of Bottrop in Western Germany. His body would never return home to Scotland but lies to this day buried in the cemetery of the Dutch city of Heerd.

That last summer at Loretto School, in Edinburgh, they posed for the camera with the easy-going radiance of middle-class boys used to have their picture taken. It is this snapshot quality that gives the images their intensity, for we see the boys casual charm, their bodies oozing beauty and life, oblivious of what the gods had ordered to be their fate.

As time goes by, the photographs acquire a poignant meaning. Those boys about to take flight, to use a worn-out phrase, ignored what we now know, that their journey would be short for many of them. Let this text be a homage to their memory, a monument to commemorate their lives, a testimony of that day in 1939 when they were happy and full of hope, that hope that young Alistair had embedded in his very name.

What is a monument? “A statue, building, or other structure erected to commemorate a notable person or event”, says the definition I found online. It may be placed over a grave in memory of the dead or at a location of historical significance. It is something that deals with death and memory, a refusal to let things be forgotten. Its aim is to prevent remarkable events or lives to go uncelebrated or places be unnoticed. A monument is about visibility.

Those are also the aims of this Quincejellytin site, but can a story be a monument? It certainly is a structure, although carefully constructed with words rather than stones. What about Patrick´s pictures then? Can they be considered a monument? In 1940, at about the same time that this story took place in what then was “real life”, art historian Erwin Panofsky published an influential book, “The History of Art as a Humanistic Discipline”. There he elaborates a theory on the distinction between “monuments” and “documents”, both being two sides of the humanistic object of study, according to him. By “monuments,” Panofsky understands human artefacts, actions, or ideas that have urgent meaning for us in the present; whilst a “document” refers to the traces or records by means of which monuments are recovered.

Monuments and documents relate specific short-term individual lives to those of long-term communities. So, yes, Patrick´s pictures are traces of those lives left behind by the passing of time but, how relevant were those lives? Can young Alistair´s short existence be described as “notable” and thus worthy of a monument? He certainly died for all of us, defending our present freedoms and his bravery and his relevance should not be underestimated.

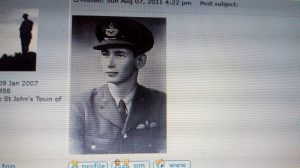

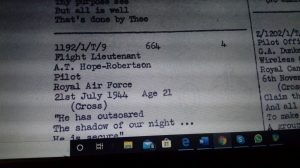

So, I set myself to investigate what happened that fateful day when his plane was shot down over the plains of Holland. The first port of call was the RAF archive, where I found a succinct service record sheet giving a skeleton of what happened the night that Flight Lieutenant Hope-Robertson was killed at the age of 21.

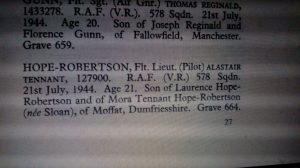

It was on the 20-21st of July 1944 at 23.05, the report said with icy precision. The plane was a Halifax MZ11, coded LK-M. It had left the air base of Burn in South Yorkshire destined to bomb the oil facilities in Bottrop, Western Germany, not far from the Dutch border. Alistair is listed as the single man in the aircraft crew. We are told that he is commemorated -i.e., buried- at the General Cemetery in Heerd. A list of medals to which he would have been entitled are given then, with no indication that any was posthumously claimed for him by his family.

“Medal”, here is a third mode of remembrance. We had first the document, the record sheet at the RAF, then the monument, that grave at the Dutch churchyard that, to quote Rupert Brooke´s celebrated verse, will forever be England. Now we have the medal, a commemoration of an event too, or a prize awarded as payment or compensation. Veterans like their medals, a physical piece of metal that materialises what is but memories as times passes and their heroic exploits in battles recede into oblivion. They are a symbol, and symbols are important for us.

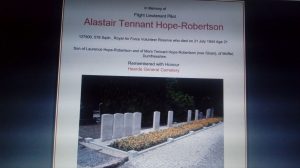

Upon further investigation, I discovered in the Imperial War Museum site that there was a further “monument” dedicated to our young hero, one less solemn but more easily accessible, as it is found in Moffat, his hometown. It is a bench with a commemorative plaque laid in a little square, outside an RAF sheltered accommodation home for ex-service personnel. “To remember always”, says the small plaque. Underneath, we read his name, the squadron to which he belonged and the dates of his birth and death.

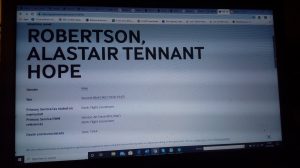

This site also offers some new nuggets of information, that he had been the son of Laurence Hope-Robertson and Mora Tennant Hope-Robertson (née Sloan), both of Moffat in Dumfriesshire. My mind briefly wandered to them, to how they would have taken the news of the death in service of their beloved son, the desolation with which they must have lived forever more. I hoped that those monuments would have given them some comfort. The pain must have been incommensurable, no matter how the war circumstances may had hardened and prepared them for it.

The IWM site mentions then that he had attended Loretto School in Edinburgh, thus connecting his war story to those pictures now in possession of Sarah Forman that were the trigger for this story. There was a quote from the Lorettonian society website:

Flight Lieutenant Alastair Tennant Hope-Robertson

Flight Lieutenant Hope-Robertson, The Royal Air Force (V.R.), was born on 19th April 1923, and at Loretto from May 1933 to April 1941. He was in the VI Form and a Lance-Corporal in the A.T.C. After being an R.A.F. cadet at Aberdeen University for a short time, he underwent training at Falcon Field, Arizona, U.S.A., and was commissioned there in August 1942. In 1943 he served for three months in the Middle East, and afterwards took part in raids on Germany. While acting as Pilot and Captain of a Halifax bomber, he was killed in action over Holland on the night of 20-21st July 1944 and is buried together with four of his crew in Heerde cemetery, near Apeldoorn.

“He was one of the most outstanding Captains of Aircraft known since the formation of the Squadron.” (No. 578)

This made me revise my guess as to the exact date when Patrick had taken his pictures of Alastair. Most likely, it would have been in 1941 and at Easter perhaps, with war already in its seventh month. Both Patrick and him must have left school to join the forces shortly after Easter, Alastair going to Aberdeen, before being flown to Arizona to train as a pilot there; Patrick to his Norfolk range.

In 1943, Alastair was posted in the middle East, which explains a picture in Sarah´s collection. He must have sent it to his friend. He’s dressed in army shorts and vest and he is smoking a pipe, looking no longer a young boy but a grown-up man, the seasoned military man through and through. He looks confident, happy in his role and totally at home in his hot exotic location, a far cry from Moffat. This was no Sebastian Flyte abandoned to alcoholic self-indulgence, but a man in full command of himself, one who, like Patrick, was determined to have a “good war”. He came back to the UK as a Flying Lieutenant, joining that RAF Squadron 578 with which he would make regular sorties to bomb German targets.

Each new document adds some new piece to complete the puzzle of events, a new trace. So, we learned that Alastair was not alone but was one of a crew of six the night in July 1944 when they were brought down. It makes a difference that he did not die alone. Nobody likes to do so. He is praised as one of the most outstanding captains in Squadron 578. The IWM web links to another site, The Scottish Military Research Group Commemorations Project, a charity in charge of keeping the memory of those who made the ultimate sacrifice for king and country. It seems it was them who laid that bench outside the RAF sheltered accommodation in Moffat.

More information is offered there on how events went that July 1944. Alastair’s plane was one of six Halifax bombers lost that night to squadron 578; 23.05 wasn’t the time when the plane was brought down, but when it left base in Burn. We learn that the plane was shot down by a German “night fighter” by the name of Major Martin Drewes. The aircraft crashed at 1.20 am, between Oldenbroek and Heerd, which explains the 20-21st July date logged in the RAF report.

It is confirmed that Alastair was not alone, but part of a crew, out of which four died, one was taken prisoner and another one evaded. They all must have jumped with their emergency parachutes. This tallies with what Sarah had heard Patrick tell, that Alastair survived the crash but, facing capture, he decided to take his own life rather than be held as a POW. The German Major that intercepted the plane was Nacht-jagd “Experten” Martin Drewes and that was his 47th “abschusse”, German for “putting down”, according to the dictionary. It was mission no. 32 for Alastair. Five of the crew were killed, the navigator was taken prisoner of war and the bomb aimer being the one that escaped.

At 1.20, Major Drewes intercepted a second plane, aircraft 405, a Lancaster which exploded violently, killing all its crew and injuring seriously the “abschusse” crew, none of whom would ever be in active service again.

But that was not all. One last document would turn up in my search completing how the full sequence of events went that night. More than a month after the demise of Alastair’s plane, in the same field, an American bomber had to “bail out” (make an emergency parachute descent) after their aircraft was also put down by antiaircraft artillery. The pilot of the plane was made prisoner by the Germans, while SS troops shot those who parachuted from it. Those who made it to the ground tried to run away, but were soon caught and made POW, except Sergeant Gordon, who was killed and would be buried at Heerd General Cemetery, next to the English men who had crashed a month before.

According to the American report, and this is the last and most gruesome piece to complete the whole puzzle of events, a corpse was found lying in that field. It was the body of Alastair Hope-Robertson, who had laid forgotten in the confusion of the day. He was finally buried next to the crew of his plane on the 1st of September in grave 664, next to sergeant Gordon, the American, who would later be exhumed and reburied at an American cemetery in Margraten, also in Holland, thus leaving a gap between Alastair’s grave and those of the rest of his aircraft crew. On his grave this legend is inscribed:

He has outsoared the shadow of our night. He is now secured.

After the war, life seems to have accelerated for Patrick. He must have been discharged from hospital sometime in 1946 and moved back home to Scotland. There are pictures of steam locomotives and cars, of the grand old mansion where he grew up and where he seemed to have returned, perhaps while figuring out what he was going to do with his life next, now that war was over and his health restored. We see a modicum of order in the land despite rationing and other emergency measures that would drag on in the immediate post-war.

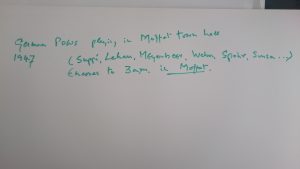

A band of German prisoners of war plays encores until the small hours at Moffat’s town hall, pending decisions about their fate. One easily imagines Patrick and his friends dancing joyously to jazz, making up for all the fun they had had to miss or had guiltily pursued while the bombs fell on, when it had seemed treacherous to abandon oneself to such frivolous amusements.

What would become of the men making up that impromptu band? Soldiers Lehan, Meyerbeer, Weber, Spohr…? One gathers they would logically be eventually returned to their native homeland, where they would engage themselves in rebuilding what had been destroyed by the mad rage of the Austrian man with the funny moustache, but I should like to think that perhaps one of them would have danced that night with a local girl and that the flowers of love bloomed out of the ashes of hate and that they would have become engaged and he stayed behind when his fellow prisoners returned. The mind wanders twenty years on and pictures Meyerbeer, the double-bass player, perhaps watching the World Cup final of 1966 in a semi in the outskirts of Edinburgh or Glasgow, where his sons would support Rangers or Celtic and listen to the Beatles in their rooms. The war receding in his mind, all but forgotten, like a bad dream, his heart torn between supporting his new home team or that of the ever more distant mother-land.

As for Patrick, he would go on to live a long and fulfilled life. He would learn to fly and own his own plane, there would be convivial family gatherings, skip trips to Switzerland and holidays in France, the study of law and a career as legal correspondent at The Times, where he would one day meet the love of his life, Sarah, with whom he lived happily till death did them part, but that would be another story.

Alastair, in his turn, would become that bunch of recorded papers, monuments and memories for those who loved him well, until today, when you are reading this story, which has tried to somewhat bring him back to life, to make him soar once more over the embattled Earth as you read this.