The third archangel

I am far too rational to believe in ghosts and I do not believe in coincidences either. And yet, there he was, turned into bronze. He was crouching over a flower bed, working as usual to try to leave the world in a better shape than it was before. I had walked past that place many times without noticing that sculpture that seemed to be him brought back to life.

José Miguel Romero Pajuelo was “my best friend”, if any of my beloved friends deserve such distinction over the rest. He died at Middlesex Hospital, in London, on April 17, 2004, if death is the right word to refer to those loved ones that are no longer with us. The death certificate signed by the coroner states the cause of his decease as a cancer-related septicemia. He was also HIV+. He had gone through a brutal chemotherapy treatment that had been successful in reducing his tumour but had depleted his already compromised immune system.

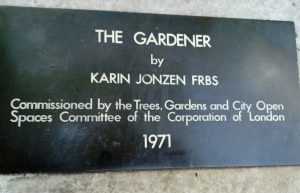

Ten years after that, I had been myself diagnosed with cancer. It was on the day of my first appointment with the oncologist that I had that encounter with him turned into bronze. I arrived early to St Bartholomew’s hospital, in London too, for what felt like an appointment with my fate. To make time and distract my mind I walked around the area in that perennial, light London rain. In a little square on Roman Wall, right in the City, I bumped into that sculpture of a boy that struck me as an image of him by its posture and the way the hair fell over his face. I got closer towards it and then I read the inscription underneath: “The gardener”, it said, the profession that he had studied at Barcelona’s prestigious school of gardening, and an activity that had become his passion.

I sat on a bench in front of him regardless of the rain, deeply surprised, silently questioning him, trying to figure out what could it mean, that unexpected encounter at that crucial time for me. After a while, when the raindrops began to merge with my tears, I woke up from my reverie, walked towards him again and hugged the sculpture, kissing lightly those metallic lips as if to breath life into him. “I shall come back”, I whispered, “one of us has to live and it seems it has to be me”.

Then, at the hospital, they took measurements to plan the exact place where the healing rays would penetrate me when my radio-therapy treatment would begin. While the Iraqi doctor and her nurses indulged in some trivial chat to put me at ease, my mind travelled back to that sculpture in Roman Wall, a monument to my best friend there, right at the heart of London. If you ever find yourself about, please go and offer him a flower.

Was it chance? I already said I don’t believe in that. My encounter could not be fortuitous. As I left the hospital, I went back and there, sitting among the autumnal leaves dancing in the drizzle and the breeze, I decided that my next writing project would be the most ambitious yet: to bring him back to life by means of words. I would interview everybody that knew him throughout his sadly truncated life and from their memories of him, I would produce a portrait that would be José Miguel and would be all of us. As that portrait would by force be tinged by my own interpretation of things, the resultant image would be neither him, Miguel, nor me, Rafael, but a composite image of both, hence the title of this text: “The third archangel”.

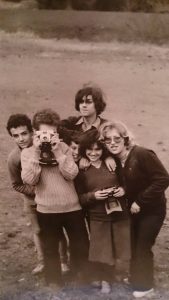

We met at primary school in Barcelona. It must have been about 1974, when we were nine. His family had moved recently to the neighbourhood from another part of town and that’s why he joined late the old San Juan de Ribera school, in the district known as El Clot. The class teacher, Señor Ortiz, was a frightful fascist. He introduced him to the class and searched the room looking for a suitable deskmate. He chose me. Perhaps it was just a fluke or may be that old curmudgeon saw something instinctively. Who knows how the machinery of fate works?

Whatever the case, there he sat next to me, never to leave until that fateful April of 2004, at the beginning of a beautiful sad spring, when he dissolved in my love for him. Neither death nor the passing of time has damped the deep love for him that inhabits my heart. On the contrary, I feel it is even stronger since it became all that I had of him. No other feeling can compare to the pure love one keeps for those who live now – only in our memories, indivisibly merged with us.

For the passing of time does not heal the pain of absence, as it is customary to say to those bereaved. As years go by, I have missed José Miguel more and more. It is as if it that shell that I grew to protect myself at first has vanished; or as if the effects of an anaesthesia had passed and I had been left with raw pain. I always find myself thinking of him. “Miguel would be pleased by this”, I say as I leave a good exhibition or a film; when I am at a mad party where a fun-loving, multicoloured crowd meets; or if I take part on a march against the greediness of banks or in favour of a better more solidary world. Miguel had a great heart and little tolerance for intolerance.

We spent two years in that absurd school, a relic from other times, until our mothers, plotting at the school gate, decided to change us to one of the many small private but state-funded “academies” that proliferated in those years throughout Barcelona. They made up with their better-prepared staff for the shortcomings of so many past-their-sell-by-date teachers that still clogged the state system back them.

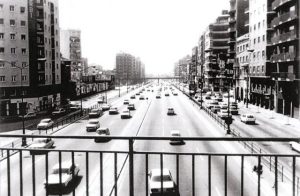

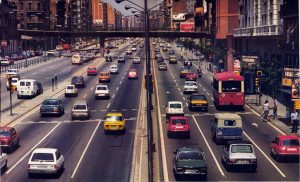

“Academía Pujol”, as our new school was called, was near a little square called “Plaza del Dr. Serrat”. It was a triangular space created by the confluence of Calle Mallorca and Avenida Meridiana. Our memories of childhood were not of running through forests and fishing in rivers Tom Sawyer-like, but memories of the traffic-crowded avenues of Barcelona before the construction of the orbital by-pass. After school, we stayed in that square until late. We used to sit at a bench eating sunflower seeds that we bought at a tuck shop in the square. It was run by an old lady perennially dressed in mourning black and her daughter. I think they were from a small village in Granada. We spent hours on end chatting, getting to know each other and the world, establishing the close bond that would tie us up till the end of his life, when we were both forty.

I remember one evening that a group of hippies came to the square and they started using the swings and the slide. Miguel and I were fascinated by the unusual sight of grownups behaving like kids. That evening we decided we would become hippies.

It was 1977 and that summer the CNT, the anarchist trade union, organised a big party at the city’s Parc Güell. They had just been legalised after forty years proscribed by the fascist dictatorship and it was a big thing. We learned about it and, as bold as you like at just thirteen, we escaped one afternoon and went to the public party. As we walked about the many stalls offering all sorts of stuff and mingled with the hippies, we felt that the times were truly-a-changing and that we were destined to be part of a new, better society. We were to be disappointed as things did not quite turn the way we hoped, but what a privilege it was to be growing up at that time of optimism, so different from now. Where did it come from, that thirst for experimentation that we had? The zeitgeist, I suppose.

That rebellious spirit was to be with us forever. At the age of twelve, we had joined a group of boy-scouts based in Calle Tenerife, an unpaved steep slope in the Guinardo district. The street climbed towards a shanty-town and it became a quagmire when it rained. In those days there were still several pockets of such extreme poverty in Barcelona, built by immigrants arrived from all corners of Spain in search of opportunities that their hometowns could not offer them. The view of that makeshift neighbourhood also spurred our non-conformism. That was an unacceptable state of affairs and, clearly, the government had to do something to help those poor people.

Every weekend we took the the train and went on hikes with the scouts. It had been a classmate at Academia Pujol who got us enrolled in the group. She was called Jacqueline and her mother was Belgian. Another girl called Maria Dolores Romero also joined. We used to have great times at weekends and at Easter and summer camp, discovering every weekend the nature and wildlife that we lacked in that urban environment where we lived. At that time, a large part of the Boy Scout groups in Catalonia had fallen into the hands of the most conservative sector of the Catalan nationalist movement. They were strongly catholic and had what we thought a socially regressive agenda. They tried to indoctrinate us but those were rebel times in Barcelona, as I say, and we were not easily tamed.

Maria Dolores Romero was quite a handful. Scout groups are divided into patrols, each bearing the name of a totemic animal from which they take their patrol-cry imitating the animal sound. You had to find too a slogan related somehow to the animal´s characteristics or behaviour. María Dolores founded an alternative patrol -and obviously not allowed- with the name of “foxy-ladies”, whose slogan was “putas y astutas” (cunning and whorish) and their patrol-cry the tachiro-tachiro with which strip-teasers are supposed to do their thing.

We all ended up expelled, if I don´t remember badly. They couldnt put up with our robust and irreverent sense of humour.

José Miguel was born in Villanueva de la Serena, a small town in Extremadura, to the north of the province of Badajoz, very near the sister town of Don Benito, rivalling it in importance as regional capital. The river Guadiana goes past very near, making the land fertile and rich. Like the whole of the Iberian peninsula, Extremadura had been invaded successively by Romans, Goths and Arabs, each of whom left their imprint. In Medieval times, it had been famous for the wool of its sheep and goats. Villanueva´s cattle fair was as important as that of Medina del Campo, in Castile.

The discovery of America was to have a huge influence in the whole of Extremadura. Pedro de Valdivia, the conqueror of Chile, was born in Villanueva and Francisco Pizarro, the notorious conqueror of Perú, in nearby Trujillo. From overseas came potatoes, tomatoes, chillies and other novelty crops, as well as the silver and gold with which bold imposing churches with rich baroque altarpieces were built, as well as sumptuous palaces and public buildings. Landlocked and seemingly remote, Villanueva had actually always been connected to the world. It was a global village many centuries before the much talked-about globalisation of today.

The researcher Javier López Linaje, in his book “La patata en España. Historia y agroecología del tubérculo andino”, places in Villanueva de la Serena the birth of the Spanish potato omelette, exactly on 27 February 1798. A Joseph de Tena Godoy and the marquis of Robledo, two enlightened local gentlemen, tried to elaborate potato bread to alleviate famines. It seems that their invention did not quite work and that it was two local women who suggested to them the idea of frying the potato in local olive oil, first cutting it into slices, instead of pulverising it into flour. Then it occurred to them to add beaten egg, thus inventing what is now the emblematic dish of Spanish cuisine.

Villanueva suffered pillages during the Napoleonic wars, but it soon recovered its old prosperity based on its agricultural wealth. Towards the late nineteenth century and early twentieth, it was a typical Spanish town, divided between liberals and conservatives, with its social clubs and bars where people met to discuss current issues. In 1914, a group of Young “Mauristas” was founded in the town. This was the origin of the Spanish radical right. They tried to stem the spread of socialism and other modern ideas that had quickly spread throughout Spain with the arrival of the railways.

The confrontation between both sides would result in the cruel Spanish Civil war. Villanueva stayed Republican, only falling into the fascists’ hands in July 1938. As in the rest of the country, a violent repression followed. The wounds of that time have not yet fully healed, as the corpses of many of those killed, buried in mass graves, have never been found.

Villanueva benefitted from the so-called Plan Badajoz of 1952, part of the development plans implemented by the dictatorship. However, the plan’s success was slow and the benefits patchy. As many Spaniards from rural areas, throughout the late fifties and sixties, many would emigrate to the big cities looking for greater opportunities for them and their children. Maruja and José, José Miguel´s parents, moved to Barcelona in 1968, when Miguel was just four. They settled first in the Fabra i Puig neighbourhood and then moved to El Clot, where we would meet at that silly school in 1974.

From America had also come to Villanueva the boleros, the corridos, the rumbas and other tunes that Jose Miguel’s father, trumpeter with a local music band, played at the festivals, outdoor dances and casino balls that mark the passing of time in Spanish small towns. I remember hearing him rehearse with his trumpet at home in Barcelona. I wonder now whether he didn’t feel nostalgia for those happy days of his youth, not that far away then, when he and his mates at the orchestra would dress up in their evening suits, their impeccably ironed white shirts and their bow-ties, dazzling the girls with both their dashing look and their music skills.

One of those girls would be Maruja, Miguel’s mother. She was a good time girl always immaculately turned out; well made up, dressed up to the nines and with perfect hair and manicured nails. She and José had to marry in a rush when he left her pregnant after one of those evenings of music and dance.

José Miguel had a niece, Nuria, who was then living in Barcelona too, where she spent long spells with her grandparents. Nuria´s mother, Tomasa, Tomy as she has always been called, had come to Barcelona with the family in 1968 but she did not stay long. She had left a boyfriend in Don Benito and would eventually go back to marry him. In the afternoons, when we left school, it was our task to pick her up from the kindergarten that she attended. It was called “Galtufas” and it was in Calle Coruña, around the corner from my home in Calle Enamorados. Back then, children still took on responsibilities like that. Our parents had started work at the age of nine or ten and they assumed that we would have good judgement at that age too.

Very near that kindergarten, at the confluence of Calles Enamorados and Valencia there was a little square with a fountain in the middle that had a bronze sculpture of a goose. That’s why the neighbours called it Plaza de la Oca, although it did not have an official name. I used to play there with my siblings as a child. We would take Nuria to play there, and she remembers it with great affection. She has taken her own children there many times now, whenever she visits Barcelona. It is beautiful how spaces are shared between generations.

Neither Miguel nor I questioned then why Nuria was living with her grandparents instead of with her own parents in Extremadura. I suppose it seemed normal to us. We would attribute it to her mother´s job. Tomy owned a supermarket and worked long hours there. It was only many years after that, when I visited Nuria and her mother Tomy in Don Benito to interview them for this story that I learned that the reason was more complicated than that.

Tomy was the eldest of Maruja and José’s four children, the baby that came out of their pre-marital relationship that had forced them to marry in a hurry. Maruja had always had a fragile mental health. She suffered a bipolar disorder that Jose Miguel would inherit. She developed a profound post-natal depression and rejected Tomy when she was born. She had to be brought up by her grandmother. Curiously, and for no obvious reason other than a strange family symmetry, Nuria would do the same with Tomy, who was thus doubly rejected, first by her mother and then by her child. Nuria refused to eat when her mother fed her but was happy to eat anything her grandmother Maruja gave to her. They developed a special love for each other. That´s why Nuria was living in Barcelona when Miguel and I first met.

“I have suffered a lot in life”, Tomy told me that day that we met in Don Benito, and one can well imagine what she must have gone through, being doubly rejected first by her mother and then by her daughter for reasons that she could not fathom. Human relationships are always difficult and family relations can be particularly fraught. Luckily, now all that is in the past and Nuria and Tomy get on wonderfully now. Maruja died many years ago.

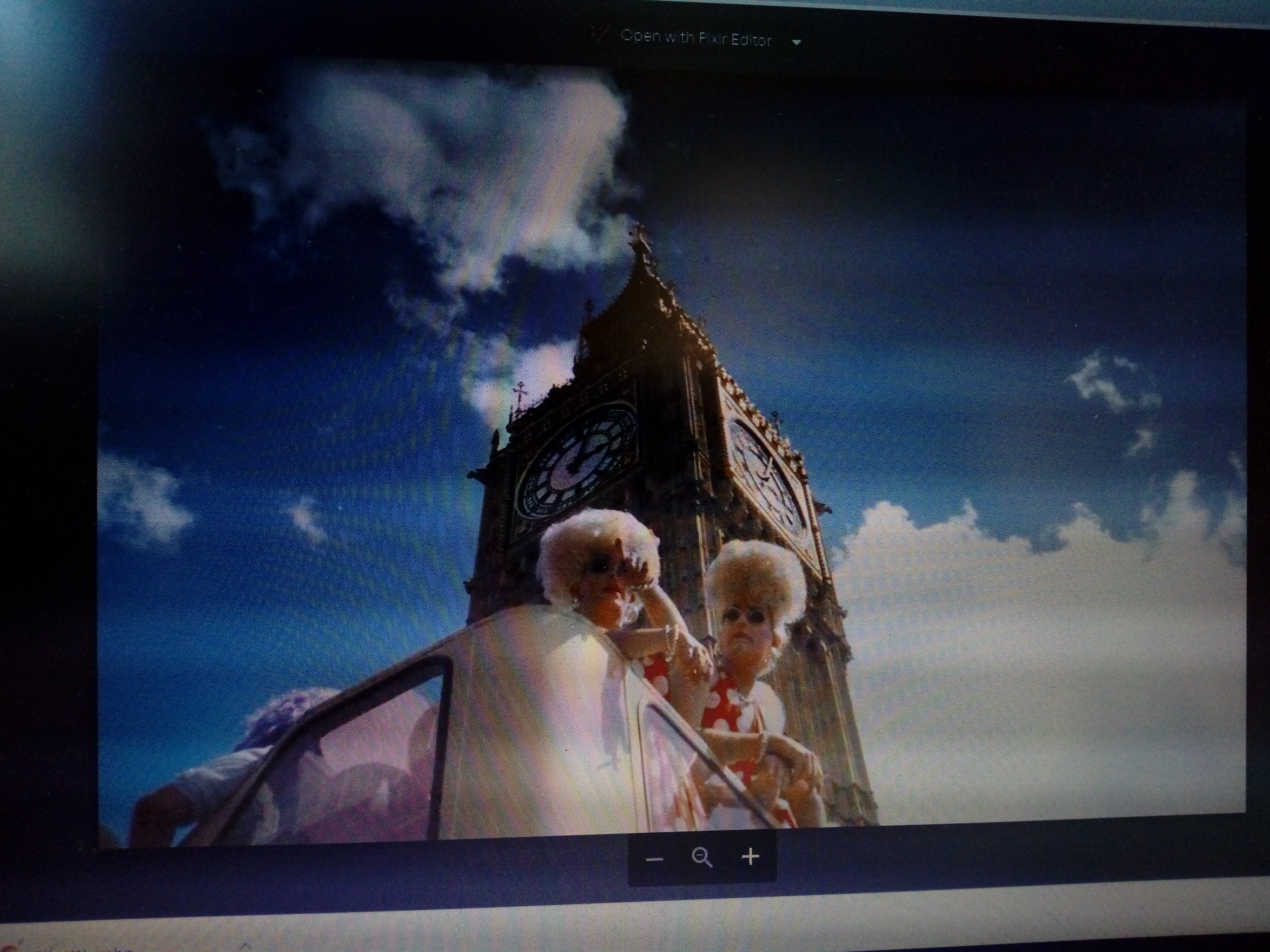

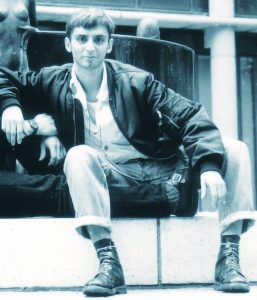

José Miguel moved to London in 1989, for no other reason than “to be modern”. In the eighties, London established a reputation throughout Europe for her alternative gay scene. It acted as a magnet for young gay men like us, who did not quite fit in the more traditional gay bars of Barcelona. Although in the Catalan capital there were already a couple of clubs that had nothing to envy to those elsewhere, there still lived in our minds the memory of more old-fashioned places where you had to ring a bell to gain access. There, suburban camp boys slow-danced with gentlemen of a certain age. They were fascinating places, but they seemed a bit outmoded to us, children of the cultural revolutions of the sixties and seventies.

In London, the punk and new wave scene of the late seventies and early eighties had given way to more complex music: The Smiths, Jimmy Sommerville with his Bronski Beat and later The Communards and, towards the end of the decade Acid House and the dance music explosion into which we jumped with gay abandon . Homosexuality, long time invisible and suppressed, suddenly took centre stage, not just in music but right at the heart of the struggle for social and political change, and that was something that appealed to people like José Miguel and me.

I had visited London regularly throughout the eighties, as I studied English language and literature at the university in Barcelona. After graduating, I secured a job teaching English for the Catalan state schools’ network but by 1992 I had become itchy and longed to leave Barcelona. London seemed an obvious place, so I asked for a leave of absence and moved to the English capital. As I arrived, however, Miguel moved to Frankfurt. At a popular gay club in Islington, he had met and fallen in love with Andreas, who would become his partner and moved to Germany with him.

You could say migration was in our bones. Not for nothing was he born in that land of indomitable Conquistadors. I like to think of Miguel as a new and more civilised Valdivia: respectful explorer of new worlds, just as our parents had done before us, when they left the world they knew in search for better prospects and wider perspectives in Barcelona.

As schoolchildren, we had been enthralled by the changing maps of Europe in our history books, where we learned about humankind’s story of faltering progress, missteps and false dawns. We were fascinated by the rise and fall of mighty empires and the appearance and disappearance of small kingdoms and republics. History was a deplorable affair everywhere, but it was Spain´s history that seemed to us the saddest of all. We were horrified at the trail of blood, destruction and irrational fanaticism that it had left behind.

We longed to go out into the world, escaping from the heavy burden imposed on us by that history that was so repellent to us. We wished for new forms of life, more advanced and sophisticated. The success of the Scandinavian social democratic model attracted us, even if their extreme weather dampened somewhat our enthusiasm for their modern ways. We felt somewhat proud that our mother tongue bridged the ocean between Europe and the Americas, but our heart was in that new old Europe that had emerged from the ashes of war.

“Catch the world in London”, used to say an advert for British Airways at a travel agency in the neighbourhood where Miguel and I grew up. Its shop window, full of “invitations au voyage” played an important part in our sentimental education. That is just what both of us would eventually do: we caught the world in London.

While in london, as he had done before in Barcelona, José Miguel had embraced a hedonist lifestyle. To go out every night, to love, to meet people and to know the world were his main activities and motivations. To his parents’ displeasure, a professional career was never a priority for him. Although he worked a lot and from early on, he never considered holding a job as a way of validating oneself personally or socially. A job was just a way to pay the rent and the expenses necessary to have a decent life. He never finished his secondary school because he wasn´t interested in abstract knowledge, but in learning things through his own experience.

He had worked first as a waiter at a luxury hotel in Barcelona, the Diplomatic, where his father was the garage caretaker. Later, in London, he worked for catering agencies or anything else that came along. As he was friendly, with a sunny disposition and very sociable, he always had free entrance at the fashionable clubs. He was also able to spend a whole night slowly sipping his gin and tonic or vodka and coke. He was always frugal, thrifty and not given to wastefulness.

He had a great talent for DIY and manual work, as well as an artistic temperament. In his earlier days in London, he took a foundation course at the London College of Printing, where he was subsequently accepted to study for a degree but, in the end, he would let it be. He had neither the perseverance nor the patience required by formal education. He was a committed anarchist, a self-taught man who liked to learn things by himself and from a practical perspective. He taught himself how to use a sewing machine so he could make his own clothes. The perseverance that he lacked for academic studies, he had in droves when he applied himself thoroughly to manual work. He was unbeatable at recycling old things, whether garments or technological gadgets.

As I type this text, I hear on the radio a live performance of Ravel´s Bolero from the Albert Hall, and music´s evocative magic transports me to our early youth in Barcelona. Then we used to visit regularly “los Encantes viejos”, the city´s second-hand market which was still at its old location where Dos de Mayo street goes to die as it meets Plaza de las Glorias, just a few blocks from where we used to live.

As the orchestra plays the famous crescendo of that musical piece, those carefree days come back to me. We used to dress in clothes bought for one hundred pesetas at the piles of stuff sold in auction by relatives of people who had deceased. “Do not bring home dead people´s clothes”, our mothers would say, uncomprehending our taste for vintage things. “God knows what illness they died of!”. But José Miguel washed and disinfected the garments and would made the necessary alterations with his impeccable sewing skills.

A film of soft-eroticism had been hyped in those days, Bolero, with the forgettable Bo Derek as protagonist. At the “Encantes”, ever eager to please, there was a stall selling cassettes with Ravel´s music, which played a part in the most celebrated scene in that film. It was blasted at top volume to entice young couples to buy the cassette and re-enact at home what the actors did.

Everything seemed stable back then, although our youth knew well that big changes were soon to come, as that is the essence of life at that age. Now that everything has gone, including our mothers and José Miguel himself, those days appear to me like a lost paradise and the body shakes and the heart misses a beat as the crescendo finishes and the London audience applauds the orchestra´s rendition of the Frenchman´s piece.

The disease that would eventually take José Miguel away from me was a mouth cancer to which HIV+ people are very prone. It appeared out of the blue in December 2003. By then, his relationship with Andreas had come to an end, though not his friendship, which was to last till he died. He had left Frankfurt after many years there and lived between London and Barcelona. In England, his condition entitled him to receive “income support”. Also, Islington Council offered him a council flat that he shared with Xavier, a friend he had met in his early days in London.

In Barcelona, through a friend he had met at the HIV support group he had joined there, he also had managed to secure the tenancy of a tiny flat on the roof of an old building very near Gaudi´s Sagrada Familia temple, whose impressive towers loomed large over the place. That flat was little more than a pigeon-loft and it was in a ruinous condition, so they let him have it for a risible price in return for doing it up.

Thanks to his great skills at manual work, that ugly duckling of a place soon became a cosy well-conditioned dwelling. The walls were painted in bright colours and thanks to the knowledge of plants he had acquired studying at Barcelona´s School of Gardening, the roof became a well-stocked garden that grew riotously under the bright blue Mediterranean skies. With bits and pieces of tiles recovered from skips, he covered the roof in a Gaudi-like “trencadís” floor that echoed the magnificent towers of the nearby grand temple. He had two cats and many birds as well as a large tank with splendid tropical fish. He had in short turned into a paradise what had been a dirty hole. José Miguel was like that.

He was happy there for several years. Friends came to stay with him from all over the world and he had magnificent parties on that roof attended by the multi-coloured crowd of friends that he had gathered throughout his wanderings in Europe. But that happiness came to a tragic end that Christmas time of 2003, when that body that had given him so much pleasure started to produce tissue wildly inside his mouth. It is true that he smoked far too much for his own good and that, together with his HIV condition, made those rebellious cells rise against him. I spent New Year´s Eve in Cuba that year with my partner and it was upon my return from Havana that he called me to give me the bad news. At the hospital in Barcelona he could not get an appointment till late January, so I suggested that he came to London, where he had full NHS rights and his HIV doctors.

He did and, happily, the English took his case with the urgency that it deserved. In a few weeks he started a chemotherapy treatment that, once completed by the end of March had destroyed the tumour. Unfortunately, that quick healing, combined with a manic phase in his bipolar condition made him overconfident and would prove fatal for him. He started going out in search of fun and love, such as he had always done. He longed to catch up with that life that he had had to put on hold for three months.

It is likely that he would have survived if he had accepted his condition as a sickly man and had stayed at home, resting warm and eating his chicken soup. Sadly, it could not be. It’s difficult to bell a wild cat. So that´s how he got the septicaemia that killed him, a clear case of a leopard that could not change his spots. He died as he had lived: drunk with life and lusting after love.

The 14 of April of that fateful 2004 I had been in Madrid, launching my first novel, “Las dimensiones del teatro”, and I naturally came back to London feeling happy and full of myself, dreaming of a literary career that later somehow stalled, failing to materialise in the way I had expected then. John, my husband, came to pick me up at Stansted airport on Friday 16 and we drove to his place in Cambridgeshire. I had planned to go to London on Sunday to go back to my teaching job on Monday 19. However, on Friday itself, having just arrived at John’s home, as I was excitedly telling him about my success in Madrid, the phone rang. It was Xavier, José Miguel´s housemate, calling to inform me that he had been admitted to A&E the previous night and that he was in intensive care. My heart stopped. I decided to drive back to London immediately, but John persuaded me to stay until Sunday, given that Xavier said no visits were allowed at all.

It was not to be. On Saturday morning Xavier rang again to tell us he had died that morning. This time I felt that the earth moved under my feet. This rapid deterioration of his health had caught John and I unaware. We had left him in good shape before I flew to Barcelona on my way to Madrid. At The Black Cap, a celebrated gay pub in Camden, we had toasted with some friends to the success of his treatment. We had been many times together there, Miguel and I, watching Regina Fong’s very special show. She was a drag act that had reigned supreme at the Black Cap before she herself had died. We had expected nothing less than a total recovery from him back then.

As there was no rush at all, John forced me to have some lunch before I set off. Then I drove to London in a state of trance, listening to Mahler’s 5th symphony while moving down the M11 motorway. As I reached the Stansted exit all heavens broke loose and I was engulfed in a deluge. Visibility was practically zero and that forced me to concentrate on the road and the music, not thinking on anything else but on navigating the emptiness ahead of me. Before I noticed, I reached the first traffic lights of town. Mechanically, I parked the car and carried my heavy suitcase to my London flat. Without stopping to think or rest, I left quickly for the Middlesex hospital, a couple of blocks from Tottenham Court Road. The hospital hall was empty. Outside, the rain kept falling torrentially. All that day is tinged on my mind with a sad grey light.

At the hospital, I met Xavier and Andreas, who had also been called by Xavier that morning and had taken the first plane available to London. We went down to the chapel of rest where Miguel’s corpse lied on a marble slab covered by a shroud, like in an old horror movie. Chemotherapy had made him lose his hair, but he always wore a hat, so it was a surprise to see him without his trademark fringe. I was shocked at how much he looked like his father, that Don José of my childhood, who had lost his hair early in his youth. Xavier and I left the room quickly and sat down at a bench outside, waiting for Andreas, who stayed in by himself. A few seconds after, we were startled by a chilling howl coming from the morgue. It was an unimaginable howl that still echoes in my head.

Then José Miguel’s nieces and his sisters arrived. We spent a week together, until the funeral that took place at Finchley’s crematorium. It was a radiant sunny day. To say that those were strange days would be an understatement. Close ties were established among all who were at the ceremony. We laughed, we cried and, step by step, we carried out the necessary formalities at the funeral parlour, the Spanish Consulate and the Civil Register.

I remember spending a long time searching for the car that nobody knew where he had last parked. I remember that Miguel´s sister´s credit card for some reason was not accepted at the undertaker´s and I had to step in and offer mine. I remember that José Miguel´s nieces put some written messages inside the coffin before it went into the fire. Then I see myself barely holding the tears as I read the little text I had prepared for the occasion and listening to the sad Schubert song I had chosen.

It all felt like a bad dream.

But no one dies if they leave behind a legacy of happiness and love. Those who knew him, his family and friends, now form a planetary system that orbits around José Miguel, our bipolar star. He lives now perpetually in an in-between state: neither here nor there, fallen between two stools, between a rock and a hard place, the hammer and the anvil, the earth and the sky, night and day. The star seemingly lost its shine, but it left a huge energy behind. That interstellar black hole that attracts and binds us with singular force, the force of his specificity because, if we are all special in our own way, he was even more so.

“The Third Archangel” wishes to draw a cartography of that solar system. Between him and I will forever be that third archangel, neither me nor him: us.