Wedding Day

These are pictures of Helen and Denis Forman’s wedding day in 1948. They were taken by Denis’ brother, Patrick, of whom there is a story published also on this Quincejellytin site, “Men at War”. That tale was based on the photographs that Patrick Forman took at St Thomas’ Hospital in London towards the end of the Second World War. He was recovering there from bone TB and wandered through the wards with his camera in hand. Patrick died in 2014. He was a keen photographer and left behind an archive of images that Patrick’s widow, Sarah Forman, invited me to go through and write a story. With Sarah’s help and some research of my own, I tried to conjure those times and to piece together the war story of Patrick and his schoolmate and best friend, Alastair Hope-Robertson, who sadly had a tragic end during the war, like so many other young men of that generation.

Patrick’s pictures of life at the hospital offered a unique window onto a vanished world. They allowed us to have a peep on what it was like to be in a major London hospital at a time of great national distress. Although private moments, Patrick’s images had a public interest angle. They presented the intersection between History with a capital “H” and the stories of those who are minor characters in the great theatre of the world.

The images which trigger this new story that I am about to tell now are equally remarkable in my view, but they lack perhaps that public resonance, at first sight at least. They are documents of a private moment that would have gone unnoticed to the world. Patrick’s images are special because he understood the power that photography has to arrest the flow of time, freezing life at a specific point, the “decisive moment”, as French photographer Henri Cartier Bresson famously described it.

What we have here is an ordinary situation, a wedding, broken down into a series of such decisive moments. Their “decisiveness” does not come from their importance as highlights of a narrative or even because of a conscious choice of Patrick’s, but out of their having been taken at all. It looks as if they had been taken randomly, but Patrick knew very well what he was doing and the effect he wanted to achieve. This artistic awareness makes the images interesting. They are documents that single out and preserve a moment in the flow of life, the flow of time. What we have is a commonplace event in any family: a wedding.

The Formans were wealthy, a condition that may raise objections to my description of them as being representative of other families, but everybody is both ordinary and extraordinary on their own terms. We may well say that the Formans were a normal English wealthy family in 1948. I will deliberately leave for later what I now know about the family’s background and about Helen and Denis. I will start the story simply analysing the images that have come to us, looking closely at them and letting them speak for themselves. Our job will be that of a detective looking for clues in order to reconstruct an event, that wedding day in 1948, and see how far we can go in recreating the social, emotional, political and economic context in which such event took place just by reading the signs that the pictures send to us. what follows is therefore a purely fictional reconstruction, an exercise of my writerly imagination, and doesn’t and can’t pretend to be a biographical account.

The first thing that stands out is the handsomeness and self-assurance displayed by the couple. They look like people who have had instilled in them a sense of their own self-worth throughout their lives. This oozes from their deportment and their physical attractiveness as much as by the pictures’ background details. Although of fine quality, their clothes are not showy by the modern standards in such events. they display a composed and serene demeanour that is the product of that which used to be called “good-breeding”, like the characters in Jane Austen’s novels. Denis and Helen are the epitome of a good upbringing and good manners, something that is the result of generations and cannot be improvised.

They are comfortable in their own skin and at ease in the world. There isn’t any awkwardness in the way they move about. They are aware that the eyes of the guests are on them, as well as Patrick’s camera, but they keep a perfect naturalness. For the well-bred, self-awareness never means self-consciousness.

They do not play the role of romantic fairy-tale couple that we may expect these days in “happy couples” on their wedding day. Helen and Denis’ marriage ceremony is very much a product of the austerities that the war had imposed on the nation. Later on, in the fifties, there would be an attempt to bring back the old glamour of the aristocratic world, the old certainties of class. It was Christian Dior in France who would spread that “New Look”, a sartorial correlate to that nostalgia and that call to order that tried to restore, in fashion, the stultified hierarchies that had been so brutally blown up by the long five years of conflict. But like the Anglo-French attempt to recover their colonial might in Suez, it would not quite work. Times had changed and a more egalitarian and informal mood was in the air.

The war had finished three years before, but its rigours were still very much present. Victory had not brought much cheer to Britain beyond the first outburst of joy after the German surrender in May 1945. India had become independent in 1947 and, with that, a whole world had vanished never to return. Britannia did not rule the waves anymore and the mighty Empire would steadily be lost in the next twenty years, leaving only a wistful nostalgia for the old days. Something that now, in the summer of 2020, is still unresolved.

Europe had suffered a big blow and the once proud continent had been taken a few notches down and cut to size too. Only the advent of the EEC, the origins of today’s EU, would later offer Europeans some hope of keeping a significant role in the new post-war order, where the United States and the Soviet Union had taken their place.

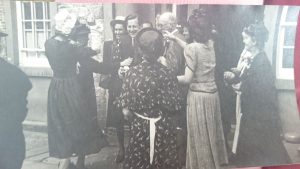

Helen and Denis pitched that change just right in their wedding. It was a low-key affair. The guests were limited to a handful of family and chosen friends. There is none of the big pomp that is customary in those events today: no grand entrance in the church, no walking down the aisle. In fact, there is no religious service at all, despite Denis’ father being a reverend minister of the Scottish Unitarian Church. Instead, we see the couple being showered with confetti as they come out of a rather ordinary building, the civil register office.

There is a modern air to the whole affair, a modernity that comes partly from Patrick’s photographic style. He took the pictures candidly, holding the camera in his hand, possibly with one of the small Leicas that had revolutionised photojournalism in the years before the war, allowing for a more naturalistic style. There is no formal posing. Patrick liked catching life as it unfolded.

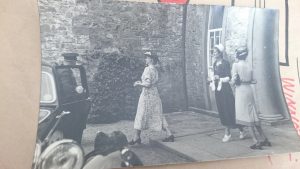

But that modernity also comes from the relaxed attitude of the bride and the groom. They don’t look stuffy but show an easy-going insouciance that we tend to associate with our contemporary times, when solemnities and staged images are out of favour. Denis and Helen were a couple that married on their own terms, fully embracing the less formal ways ushered in by the post-war context. Helen wears a simple flowery dress and a modest straw hat, with no concessions to sartorial extravagance. She is no “queen for the day”, and god forbid that, she seems to say. Later, she changed into a tailored jacket and skirt suit that reminds us of the uniforms women wore during the war. The future Queen Elizabeth herself is an example that comes to mind. She became the first female member of the British Royal Family to be on active duty in the Armed Forces when she joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service. She was happy to be pictured in her army dungarees, busy working on a motor engine, a traditional man’s job. But the war had blurred strict gender roles. Helen’s more masculine dress style was also donned at the time by Argentina’s Evita Perón, whose tailored suits were the outfit of a woman who is no longer resigned to take an ornamental role and who is keen to look at men eye to eye.

The married couple knew the times had moved on and had no regrets about it. They embraced the new order with great gusto, ready to take their place in it and to work hard to rebuild the country along more democratic and egalitarian lines, both in terms of gender roles and social class.

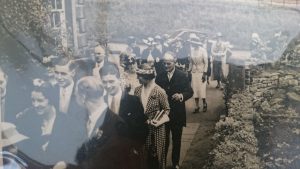

Patrick’s photographs present us with a vivid gallery of characters around the sparkling couple. They were mostly young men and women, all well-heeled, with a smile on their faces, ready to enjoy the special day. They were dressed smartly, but not lavishly. The men looked dapper in their suits, bareheaded with slick hair neatly parted and a flower in their buttonholes. The ladies wore summer dresses and were well-coiffed under their hats. The general tone was one of effortless elegance. Charm and discretion ruled. There was no stridency, as it suited the austerity of the times.

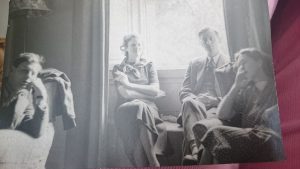

The pictures capture well the subdued mood that so well mirrored the age. Everybody was slim, as if showing signs of the deprivations endured by both rich and poor during the war, when food was strictly rationed. But they all distilled panache, confidence and joie de vivre. Denis’ parents also looked relaxed and content with the way things were. Reverend Adam Forman lit up his pipe as his wife smiled amiably at him. The picture had been taken indoors and it looks as if they had been caught unaware, their conversation interrupted by Adam’s wish to smoke. A quiet private moment turned by Patrick’s camera into a decisive one, for we can now infer many things from that image he so casually took. In the background, blurred, we can see the figure of a woman that could be part of the domestic help. Both Reverend Adam and his wife appear perfectly happy, a couple who had survived the horrors of the war with no child killed. No wonder they should look pleased.

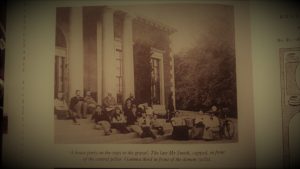

After the ceremony at the registry office, they all must have moved back to Dumcrieff House, the Foreman’s home, to enjoy a wedding repast which looks also frugal and laid-back. We see old uncles and aunts sitting at a table, all informally enjoying themselves. Patrick’s camera snapped it all with his usual stealth. Some of the guests were unaware of him and carried on with their talk, while others realised he was there and tried to pose, like the lady that was holding her cup of coffee and looks at us now, forever smiling from the distant past.

Coffee must have been a small luxury in those days, something to relish and enjoy, and sugar was certainly difficult to come by. There is no wedding cake in the pictures, maybe because of Patrick’s dislike of staged scenes, but just as likely because Helen and Denis may have not wanted one. It is well-known that, under rationing, couples had used mock cardboard and plaster cakes that looked like the proper wedding thing, inside of which a smaller and more ordinary one was hidden and produced, the cardboard one being just for show. But that could hardly have been Denis and Helen’s choice.

The upper classes of Britain had to adapt to those new more demotic times. The reconstruction effort needed allowed for nothing but sacrifices from all. A new Labour government had been voted in the first election after the end of the war, in 1945, shockingly defeating Winston Churchill, the war hero. They had created the National Health Service to provide universal care for all, and the National Insurance Act of 1946 to provide sickness and unemployment benefit for adults and retirement pensions for the aged. A massive programme of slum clearances was set in motion, substituting the old grim tenements with modern council homes.

The age of Empire was over, but things were looking up. The new publicly funded institutions required managers and enlightened administrators and Helen and Denis were ready to take on those roles. As they lounged in the drawing rooms of the Georgian house, the young generation smoked and talked, determined not to end dissipated like the Bright Young Things of the nineteen-twenties, those jaded and spoilt aristocrats who partied and played while Rome burned.

Most of the young people in the pictures must have all been recently demobilised and, although they looked casual and chilled, they knew the Gargantuan task ahead of them. They would have to adapt, work hard and contribute to the transformation of the old into the new. They would soon be called to London, Edinburgh, the provinces and whatever was left of the old Empire to take charge of things. Meanwhile, like Mr Churchill, the older generation knew their time was up and that they ought to take a step back and let the young organise things their way.

The wedding celebration seemingly went on for a whole weekend. The following morning, the group gathered for breakfast and then went for a walk in the hills around the house. Patrick’s camera followed them, moving about freely, fly-on-the-wall style, searching for those decisive moments that would capture in a single image the essence of the event, that is to say, the essence of life. There is a film quality to his reportage, for his photos aim at catching movement itself. No one is standing still in them, a mobility that seizes the spirit of the times: evolution and change.

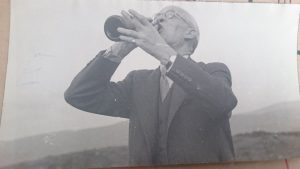

The bride had put on that tailored suit which, paired with her straw hat, gave her a look that was both professional and informal. The superb photos Patrick took that day of them at play up in the moors were his masterpiece. In them, his great skill came into its own. With his precise eye, he captured perfectly the informality of the day. They all shared some champagne, passing the bottle around from hand to hand. Helen drank directly from it in a most unladylike way. She smiled at the camera, knowingly subversive, relishing her freedom from the starchy ways of the old days, away from the prying eyes of servants, far from the city mores that she was determined to shape. They even managed to make old Adam Forman tip the elbow, the old Reverend of the Unitarian Church.

The gathering had something of the ancient pagan ritual, a ceremony just for the initiated, the inner core, as if Helen and Denis had led everybody into a Bacchic feast, making them celebrate their marriage in their own way, riotously, jovially intoxicated; drunken with life and merriment. Up there in the high hills, they could all be themselves. Their infectious enjoyment at that moment reaches us many years down the line, as a symbolic image standing for that bright moment of illumination, an epiphany, a revelation or realization, the decisive moment indeed. Patrick was surely proud of this images. He could see with an accurate gaze the compositions and the expressions that his subjects offered him, and with perfect intuition he clicked his camera at precisely the right time, to produce a splendid tableau vivant.

Helen had fastened a twig of heather to her brooch. Perhaps Denis had offered it to her, for heather flowers symbolise good luck, as well as independence and confidence. They grow in places that are quite hard for any other flower to grow. According to common lore, you give a bouquet of them to let someone know that you think they are confident and self-assured and that you trust that they can handle any difficult situation that they may encounter in their lives. Having heather at home or carrying one with you is meant to attract good fortune.

And there were indeed auspicious vibrations in the air that day. It feels as if a window had just burst open, letting fresh air into a stuffy room, bringing in the scent of the wild moors and a licence to dream. There is a certain sense of exhilaration in the scenes we see, the triumph of the outdoors against the fashionable towns to which, however, they would have to go back sooner or later. The married couple looked ahead with glee in their eyes. These were people that had not just defeated the Germans, but a whole old world. They knew that the future was theirs to seize, they understood the real significance of that victory and were ready to take their chances and fly with the spirit of the times, leaving the past behind and moving on to the bright times ahead. They looked very much in love, relishing their own liberation and the exciting possibilities that opened for them.

They had put behind them not just five long and uncertain years of war, but a thousand ones of social restrictions. They had the look of a Prometheus that had just been unbound. Denis and Helen’s liberated ways prefigure all that was to come: the new music and new art forms, the cultural changes, the philosophies from the East, women’s liberation, the sexual revolutions. For them, the future was now.

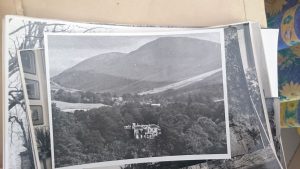

Dumcrieff House is a character more in this story and the perfect counterpoint to the movement of human life that Patrick immortalised. In contrast with their transience, the house stands still and fixed, a true “propiedad inmobiliaria”, as property is called in Latin languages, meaning literally that which cannot be moved or transported, what in English is called “real estate”, an interesting concept too, for it implies that all other things, and indeed those who own them, are nothing but unreal.

And we could well say that is the case, for Dumcrieff is still in the same place, still real, but its old occupants have now all gone and are no more. It has been passed on to others, just as it had previously belonged to different owners before them. Buildings often stay put long after we have died or moved on. Dumcrieff is indeed still there and it may well be there for hundred years to come, but it is a long time now since the last Forman roamed its rooms.

Who has not asked him or herself once, alone in a room at home, about the people that inhabited it before, how they lived the space that is now ours and what furniture arrangements they had, and whether they were happy or wretched? We all live surrounded by ghosts.

Yes, unlike the Forman family, who were in a permanent state of motion, the house stood unmovable and unmoved, like a permanent stage on which different actors come and go, trying their best to perform their roles. Reverend Adam Forman had bought the property after the First World War and would live in it for fifty-three years, until his death at the age of 103. Before him, it had been occupied by the heirs of Lord Rollo and Elizabeth Rogerson, the granddaughter of a Dr John Rogerson, who had built the present house in 1806 in the architectural fashion of the day, those Palladian forms that would eventually be called Georgian style. It had been in a ruinous state when he purchased it from his friend Dr James Currie, the biographer of Robert Burns, the Scottish national poet. Dr Rogerson retired to his native Scotland after spending most of his life in St Petersburg, where he had been the private physician of Catherine the Great, the Russian Empress. It took him almost twenty-years to have it built and, by the time he came to live in it, he had only three years of life left.

Its previous owner, Dr Currie, had bought it after the death of Colonel William Johnstone, who had rented it out for two years to John Loudon MacAdam, famous for having invented tarmac in 1792. It is said that the large sandstone roller that he used to test his invention is still somewhere in the grounds, a testimony to how people and events that no longer exist always leave a trace behind them.

The parklands and landscape had been planned and planted by Sir John Clerk and his son in 1727. The original house had been erected in 1684. According to all accounts, it had been a draughty and forbidding fortress in the style of the ancient Iron Age Scottish brochs. Those were times of warring clans and castle-like constructions a necessity and not a modish whim. In 1482, the Murray family had been granted possession of the land by the Duke of Albany, son of James II of Scotland. and they had since been entangled on a feud with the Glendinng family of nearby Westerkirk.

Many plots had been staged in those hills where Denis and Helen had drank their wine on their wedding day in 1948. Many changes had taken place since then and and many mighty warriors and proud landlords had turned into ghosts. Patrick took pictures of the empty rooms of Dumcrieff House with that objective eye of his, showing no emotion in his dispassionate presentation of his old childhood home. His pictures bring to mind the interiors of Danish artist Vilhelm Hammershøi, who painted eerie rooms devoid of humanity, spaces that trigger the question of what places and objects look like when we are not around. He also painted people alone in those rooms, unaware that they are being watched. In that vein, Patrick caught his mother, Flora Forman, née Smith, arranging flowers in a vase. It is strange and somewhat unsettling image. As we look, we become aware that the room has a solidity that she lacks. Her indifference to her son’s camera seems to mirror that of the room itself towards her.

Dumcrieff is in Craigielands, not far from Moffat, in the Scottish county of Dumfries and Galloway, which borders with Cumbria, in England. As all border regions, the area used to be a lawless place back in the day when cattle robbing was a way of life for the clans who controlled those lands. There is a place called Devil’s Tub nearby that is named after the place where the Johnstone clan used to hide their stolen cattle. This lawless past would go on until well into the seventeenth century, when the rivalry between the Glendinning and the Murrays was in full swing.

But by the time that John Rogerstone came back from St Petersburg and built his Palladian retreat, things had mellowed considerably. He had spent his life in Russia checking that Catherine the Great’s lovers were free from venereal disease. Health was becoming increasingly important and soon would make the fortunes of Moffat, whose medicinal waters would attract many visitors in search of a cure to their ailments. By the mid-nineteenth century it was a respectable, fully-fledged Victorian spa town, thanks to the sulphuric quality of its spring waters. Fashionable people flocked to drink and bathe in them, in the hope that they would alleviate their rheumatism or gout.

Sulphur is of course the scent of the Devil and there is something singularly Victorian about that mixture of the holy and the macabre, a tension between wilderness and restraint. Moffat Spa had that element of tamed romanticism, of nature put at the service of those with money and leisure in their hands, the origins of modern-day tourism. That mix of the heathen and the divine is very much the essence of Craigielands and of Scotland at large, with its vast wilderness and its Presbyterian heritage.

That cultural landscape had very much informed the character of the Reverend Adam Forman, who was said to be quite a maverick man. Like in his photographs of the house, Patrick presents the landscape around it in all its indifference to any human endeavour, devoid of people. We see his car parked on an empty road somewhere up the moors, a strange city artefact lost in the eerie countryside, an unforgiving place of clouds and grassland.

There is Moffatt water too, the brook that runs through the estate, a source of trout and sport, of bathing in summer days and ice-skating in the frozen wintertime. The water runs boisterously under the trees. Patrick has caught it in all its wild loveliness. We can almost hear the gurgling sound of the crystalline stream and the blowing of the wind rustling through the canopy of leaves. The scent of peat and heather oozes out of those pictures and one can imagine deer coming to drink and to munch by the riverside lawns.

The Parkland that Sir John Clerk and his son George had planted is still there, a reflection of the Scottish eighteenth-century enlightenment dream: nature perfected, civilised by man´s intellect. We see the house from above, an aerial view from one of the surrounding hills. Its elegant proportions are dwarfed by the conifers that ground around it, which arises a certain feeling of unease, for nature lurks almost menacing, as if bidding its time to swallow it if given half a chance, ready to reclaim its rightful place. In the event, not even the most solid house is free from the impermanence of all things.

Adam, the Forman patriarch, was a man of both religion and science in that enlightened Scottish tradition. He had learned from Isaac Bailey Balfour, an eminent Scottish botanist, about the antiseptic properties of sphagnum moss, an excellent material for dressing wounds. During the Great War, when cotton bandages were in short supply, Reverend Forman quickly organised local squads of volunteers to pick up that material that grew in abundance in the inaccessible bogs that belonged to him. They collected tons and transported it to the station on a special trolley that he had devised. There are several documents in the Edinburgh botanical gardens about the history of this endeavour, the Reverend’s finest hour.

Mary Duncan a painter that, like so many other women artists seems to have been forgotten by the world of art, did some very fine oil paintings depicting the process. I could not find even an entry about her in Wikipedia, only some news on the page of an auction house announcing the sale of some paintings by her that used to hang on the walls of Dumcrieff.

So, that unforgiving landscape that at first sight may seem just fit for the bleak setting of a Walter Scott romance, or the background for a holiday for those searching for the sublime desolation of the moors, had in fact once played a crucial role in the distant and devastating Great War.

After that beautiful weekend “en famille”, the time to say farewell arrived for those that had gathered to participate in the event. It had been a lovely and unusual wedding that they all had enjoyed but all things must end. In Patrick’s images, we see a buzz of cars and people lingering before slamming the doors shut. Kisses were blown and hands waved; they embraced as everybody left for the train station. The jolly confusion and merry fuss customary of such moments of leave-taking was duly immortalised in an array of fine pictures documenting people’s depart. One can almost hear the exchanging of remarks, the well-wishings, the promises to return, to write letters and send postcards or make telephone calls to stay in touch. Hasty arrangements were made to meet for tea in town or visit each other or go to the theatre or a cocktail together at some vague future time.

Taxis arrived to ferry the guests to the station, where trains were waiting to be boarded. Fast and nervous adieus were given again, repeating the ceremony of confusion that went on before they left the house. We can see mothers-in-law being reassured and goodbyes said to aunts from the platform or from the windows of the moving train. There is a fashionable glamour to it all. The old English railway station is more than a place, it is a literary topos. It has its own iconography and its own references and associations with dramatic moments in films. David Lean’s “Brief encounter” comes to mind. Those who leave and those who stay participated in a well-rehearsed scene that Patrick captured with his usual unobtrusiveness.

Once on board, the passengers would have travelled to Dumfries and across the border into England at Carlyle, from where the train would head south to Liverpool passing the wild scenery of Cumbria all the way to the mill towns of Lancashire, and then down to Crewe, Birmingham and finally, far away, London in the South East, a world apart from that superannuated Victorian age they had left behind at Dumcrieff, a house impervious to the changes of the age, a self-contained world of servants and wealth made on the sale of Lancastrian textiles to the captive market of the Empire. By then all that was doomed to go. The new Britain they travelled to was a post-industrial one, a service economy and a consumer society along the American lines. Twenty years on, by 1968, the country’s best export would be the music of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. The old hard power of gunboats and slave work changed for the ability to co-opt and seduce rather than coerce.

It is no coincidence that the professions that awaited Denis and Helen down south would be arts-related. They both worked at the British film Institute, where they probably had met. Denis, who would eventually be knighted and become Sir Denis, would become its director and later deputy-chairman of the Royal Opera House. Most famously, he was the chairman of Granada television in its glory days. It was under his aegis that the famous Coronation Street soap opera was commissioned, a show celebrating working class life.

Helen was an Oxford graduate, which already singles her out as a pioneer, for the venerable university did not allow the matriculation of women until 1920, a mere twenty years before her time. Both Helen and Denis left Moffat running away from a lifestyle that was decadent and somewhat nuts. They had affection for the place, but felt no nostalgia or loyalty towards that crumbling ancient regime.

They were the future, the winners ready to take it all. Once settled in their compartment, they would not look back neither in anger nor in wistfulness, ready to join the new Britain emerging from the ruins of the old: they would go on to be the architects of that soft power, contributing to the spread of British values throughout the world by means of modern technologies: the mighty media. In that, as in many other things, they were pioneers of the present times, in which information, entertainment and communications -intangible stuff- have taken the throne that once belonged to the manufacturing of real stuff.

Except for a few details such as the jobs they did later on, the information about Denis and Helen given so far has been an exercise in imagination based on the pictures Patrick Forman took on their wedding day.

The texts above have been an ekphrasis, as the technical term goes, that is, the use of a detailed description of a work of visual art as a literary device. Patrick Forman’s a mute presence recorded what he saw, unnoticed as much as possible, letting his subjects move free and relatively unselfconsciously.

But that is only one possible approach. Others are just as valid. Family history and genealogy are two popular ways of dealing with the past. This involves a search for “truth” as kept in archives and civil registers, scanning and evaluating any official document attesting the existence of somebody or something: medical or legal records and such like.

Then there are memoirs or biographies, if the searcher is lucky. These are narratives of personal experience told by an individual or gathered and re-told by somebody else. However, the aim of this website, Quincejellytin, is not to do family history, but to offer an imaginary recreation of someone´s lifetime or of some specific past event from the bits and pieces that we all leave behind, mementos and keepsakes, as well as the accounts of people who had first or second-hand memory of such people or events, when such are available. The interest lies in the stories of “history”. After all, history can be somewhat suspect, for all records , no matter how carefully kept, can be misleading or subject to manipulation by the recorder as well as to misinterpretation by the historian or the reader.

Denis and Helen were real people with real lives, not fictional characters in a novel. So, I was curious to see what online trace they had in this age when seemingly everything we do has left a digital track somewhere. Sure enough, a wealth of information on my subjects was available at a simple click. Both had indeed, as we gathered from Patrick´s pictures, joined the new world of media and culture, two industries that gradually would gain a pivotal role in the British economy.

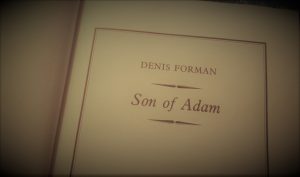

Denis would be head of Granada television in its halcyon days when the Manchester based company commissioned Coronation Street among other important shows. Holding such top job in the cultural industry, Denis’ track on the internet is rather a large one but, what is best, I found that he had written several books, one of them his memoirs of growing up in the between-wars years at Craigielands.

“Son of Adam”, published in 1990 , describes his upbringing, and confirms everything that I had guessed from the pictures of his wedding, mainly that conflict between the old and the new encapsulated in a love of jazz and the new American ways, and his parallel rejection of his father’s values, most notably his priggish Protestantism and his complacency with a world that was already on the wane. His book was even turned into a film called “My life so far” in 1999, starring Colin Firth, although it seems that the script had suffered considerable alterations from the original book.

As for Helen, she was already a producer of documentaries at the time she married Denis. She was employed by the then Imperial Institute and had previously worked for the Ministry of Information during the war. She would later join the BFI, of which Denis had also been chairman, and where possibly they had met. She had joined Films Division at the beginning of the war, an institution that took over from the GPO as chief maker of documentaries about life in Britain. Thus, by 1948, she was already a thoroughly modern and independent woman, as we had guessed from Patrick Forman’s pictures.

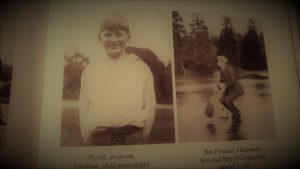

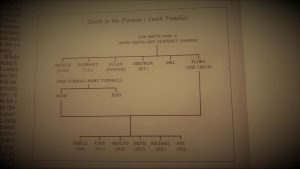

“Son of Adam” was certainly very informative, as indeed were several interviews and other documents about Denis found in the internet after a quick browse. He had been born in 1917 and had two older sisters, Sheila and Kaff, and an older brother, Sholto, as well as two younger ones, Michael and Patrick, our photographer and my friend Sarah´s husband. Denis seems to have been quite a handful: bright, inquisitive and strong-willed. He did not suffer fools gladly and he did not swallow easily any old nonsense. He could spot bullshit by a mile, and soon found out that being naughty was more fun than being good. He was a self-confessed attention seeker and preferred hanging out with the servants downstairs than listening to the religious drivel that his parents exchanged in the dining room upstairs. Denis honed his skills on popular taste down in the kitchen and mixing with the farm hands at Craigielands.

In interviews many years on, he still displayed the self-assurance and self-control that we appreciated in his brother Patrick´s pictures. Denis was a rebel who developed a somewhat condescending antagonism against his father, whose old-fashioned views and amateurish attempts at engineering made him cringe. Denis comes across as a bit too full of himself as well as full of contradictions. Overall, he probably was quite likeable on a good day, but best avoided when crossed. He possessed a wicked sense of humour but also a short-fuse.

Helen died in 1987, leaving behind two children by Denis: Charlie and Adam. Denis married again in 1990 and died of a heart attack in a nursing home in London, aged 95.

Dumcrief house is still standing today in its secluded valley near Moffat. It remained the family’s possession for about fifty years until the death of Denis’ father at the age of 103. The estate was sold by auction in the early seventies and then re-sold to another family a few years later, who lived on the estate for some 20 years. It was then sold privately in 2008 to the current owners – a local family who claim ancestral connections to the estate dating back to the 15th Century. However, they do not live there. Nobody can really afford or would even like to live in such a place anymore. It is offered for rental to people with money and a taste for the “Georgian experience” as seen on endless period costume dramas. This is how it markets itself:

Exclusive-use country mansion near Moffat in southern Scotland. Accommodating up to eighteen guests in nine luxurious bedrooms. The mansion is available self-catered or fully staffed

Experience the rare privilege of spending a weekend, short break or longer holiday in your own Georgian Mansion set in private grounds within the historic Dumcrieff Estate.

The mansion can be hired for two nights or more and is the ideal place to celebrate your special occasion including birthdays, anniversaries, family reunions or just to enjoy a relaxing getaway with family and friends.

Small Intimate Weddings & Marquee Weddings can be arranged.

It brings home what the French philosopher Guy Debord wrote in 1967 about how real life has been replaced with its representation. Life has been turned into a series of “experiences” Debord argued. What was once a house lived by a family and an economy based on the land around it and the transformation of raw materials into products has itself now been commodified. People pay good money for pretending to be the lords of the manor, simulating that they live in the days when the house was built. As another French philosopher put it: “The simulacrum is never that which conceals the truth—it is the truth which conceals that there is none. The simulacrum is true”. So appropriate that the house should now be used for weddings, those events that have been disneyfied and turned into “experiences” instead of being a sacred rite.

But perhaps the most striking thing i found in the vast repository of the wide world web was to discover that their son Adam Forman was an artist that shared my own interest in the way time and death destroy and transform everything, as well as a curiosity for what remains of us when we pass away. In his website: http://adamforman.co.uk/press-release-how-do-we-remember/ , I read about an art piece he had shown at an art gallery in London which was partly based on his mother, Helen de Mouilpied, as was her name before she married Denis. It had been exhibited in March 2019, one year before I finally started to interrogate the cache of photos of Helen and Denis´ wedding that my friend Sarah, Adam´s aunt, had inherited from her husband Patrick.

Like mine, Adam´s work is a reflection on memory and what is left of us once we die. In that art piece he presented artefacts that had belonged to his mother and tried to figure out why she kept them and how they were significant to her, in an attempt to bridge the gap between our own ideas of ourselves and how others view us, once we are gone and turn into other people’s memories.

There was a second part of the exhibition unrelated to Helen’s life, but still connected with the idea of time and how photographs document the transient. The same photograph was taken every day for a year at different times of the day at the same London spot and then transformed into paintings and drawings. “The passing of time”, read the blurb of the exhibition, “and the observation of everyday street scenes and surveillance have been recurrent themes in Adam Forman’s work. Being watched, watching and observing are ever present in these images, as is the act of clandestine photography on the closely observed crossing.”

Well, he seemed a man after my own heart, Adam Forman, and what an interesting interplay of looks: Patrick looking at Denis and Helen on that remote day of their marriage in 1948. Denis looking back at his family in his memoirs, “Son of Adam”. Then the director of the film “My life so far” looking at all those memories and changing them slightly, fictionalising them to make the story more dramatic to the viewers eyes. Then there is me watching Patrick look and second-guessing his looking at Helen and Denis and finally their son Adam looking at his mother and reflecting on what all this looking means.

We are all entangled in a network of relationships across time and space, a network of looks. The aim of this text and of this site in general, just as that of Adam Forman’s art piece, has been an attempt to observe and describe that constellation of looks. Our lives extend beyond our time and our individual minds. We are all, ultimately, part of one same tapestry stretching far in time and space.

There is not a before and after or, if there is, it all depends on who or what we decide comes first, on whose look we are going to use as a starting point. At the end of the day, we are all a series of interconnected events and objects: the photographs, the house, the place, the English language, the books written, the lives lived.