Daddy Cool

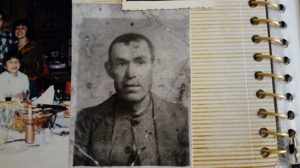

My father had been coming in and out of hospital all through the Christmas season in 2017. His condition was nothing extraordinary although it certainly was life-threatening: ageing. He suffered from respiratory insufficiency caused by liquid building up in his lungs, which provoked the malfunctioning of a heart valve. He also had kidney trouble. Not a pretty picture, all combined. They treated this with pills that kept him stable but had contradictory effects. So he had to go to hospital regularly to have the chemistry adjusted. Doctors did their best. Despite the savage government cuts recently applied, the Catalan Health Service seemed to function with great compassion and efficiency, even though the wonderful medical staff were often stressed to breaking point. You often had to wait long hours on a stretcher in a corridor waiting for a free hospital bed, uncomfortable and stressful for both patients and those accompanying them.

Dad took everything with his particular and not always understood brand of Southern humour. “Ask the doctor to come”, he said to a nurse who had come to ask how he was feeling on one of those days when he had been seemingly forgotten on a stretcher at A&E,: “put him to the right hand of the stretcher, with yourself to the left. Bring a cow and a mule and there you go, we have the manger ready for Christmas Eve”. He knows there is no solution to his problem, just managing it the best they can, which they do.

My husband John, and I had met for lunch a couple of times with him and his partner, Amparo. They take care of each other. It’s hard to be old and it is sad to be old and alone, so I was glad that dad found her after my mother died many years ago. She had also lost her husband some years before so they were on the same boat. Amparo is a kind woman, as well as an excellent cook. In the fifties, she used to work at a French restaurant in Barcelona. Her “paella” is second to none.

“This is the real Christmas”, dad said to us on the last day we lunched together. I knew he was thinking of our family’s “official” Christmas Eve dinner, when neither John nor Amparo were present. John because he always spends the festive season back in England, with his sister and her husband, who is a Church of England pastor; and Amparo because she’s an intelligent lady and knows when to make herself scarce. On that day the family meets at my sister’s for dinner and to exchange presents like we did when mum was alive, but dad found it increasingly trying dealing with large groups and late nights. Christmas Eve dinner is always a bittersweet occasion for us because mother died precisely on that very day. That’s why Amparo chooses not to attend.

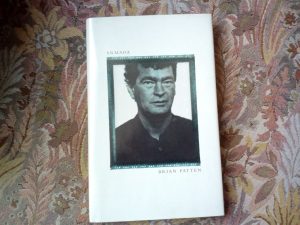

I will never forget the day my mother died. I was sitting by her bedside when she started a heart-chilling prolonged snore that ended in a terrifying last breath. I had been reading a book that British poet Brian Patten wrote on the death of his own mother, “Armada”, and I was stopped on my tracks. Extraordinarily, the last verse I had just read was: “You are now dissolving in my love for you”. I would eventually ask my brothers and my dad to have those words, translated into Spanish, as an epitaph to be inscribed on her grave. So, Christmas time is not such a happy occasion for us.

It is also exhausting for dad to start dinner at ten, wait for the present-opening ceremony at midnight and then eat turron and drink whisky and cava until the small hours. He flags, and who can blame him? I do tire too after the long day running on errands, wrapping presents and tidying up the flat. By midnight, I am just ready to crash.

It has never really been the same without mother, who was the soul of Christmas, providing for all of us. Tremendous thing death is. One never quite reconciles with the absence of loved ones, and it certainly doesn’t get easier with time, not for me at least. More to the contrary.

After his intimations of death at the hospital that year, it was sad to say farewell to dad when John and I left for England, where we live. He’s an amateur painter and we had been to his flat, where we were shown his latest work. He stood outside the door watching us walk down the long corridor towards the lift. I turned several times and he was still there, waving sadly as our eyes met. “We know what he is thinking, don’t we?”John said, as we descended to the ground floor . We were all pained by the thought that may be the last time we met.

I did my best to disperse those dark clouds. “Dad, you can´t die in Catalonia”, I said to him cheekily, knowing how firmly in the pro-union camp he stood on the eternal Catalan independence question. “You can only die in the capital of the state”, I joked, promising we would go to Madrid for a few days when I returned in April. We would go to see Rayo Vallecano play and then to the Prado to see the Goyas and the Velazquez. “If you like, you can die there”, I said, “dramatically in front of the Meninas so your death would be reported in the local news”. Man dies as he fulfills long-cherished dream, the headline would read.

Dad laughed, but his eyes lit up. He said he had been wanting to go to Madrid for a long time, a city that he loved and where he always wanted to live but moved to Barcelona instead under pressure from his sisters, who were already living there and offered him the help and support he would need to move with three small kids.

That New Year’s Eve, as we did the Spanish ritual of swallowing twelve good-luck grapes with each of the last twelve strokes of the old year, all I wished was that dad would make it to Madrid in April.

It was a challenge but April came and we lived up to it. Dad survived Madrid. I rented an apartment in the centre of the capital, where we stayed for five days. It was an old palatial building designed by Villanueva, the famous architect of the Prado Museum. It had a grand old staircase that looked like something out of one of Escher’s puzzling images, but mercifully with a modern lift fitted in too, for dad was not one for efforts of any sort. “We have come to Madrid to die”, I joked with him, as if we were in town to visit one of those famous death clinics in Switzerland where people go to put an end to their sorrows and pains. However, not only nobody died, but we had a good convivial time and returned home with our heads full of lovely memories and our bellies full of Madrid’s rich foodstuff.

As the weather was not good, it was cold and dad had limited mobility, we hardly ventured beyond the nearby Plaza Mayor. We sat in bars, drinking “cañas”, watching people go by and the rain fall as we listened to the waiters’ exchange banter with each other while efficiently going about their job. We received friends in the grand salon of our flat and met for the first time with Elise, the daughter of a cousin of us from France, a delightful intelligent woman who lives in Madrid. Dad enjoyed being at the centre of things, included in all our plans and loved by all our friends.

We decided not to tempt fortune, though, so we did not visit the Prado after all, but took a taxi and went to the Thyssen gallery instead. The ride from our flat was a tourist tour in its own right, taking us through Puerta del Sol, the Spanish parliament building and past Neptuno and Cibeles, the two grand fountains along Paseo del Prado. Dad was delighted to see all that from the comfort of the car. The exhibition we saw at the art gallery was about fashion in the work of Joaquin Sorolla, a Spanish painter my father likes. We enjoyed engaging with the artworks, discussing them, as we moved from picture to picture, like birds from one fruit to the next. At some point we must have got carried away and talk a bit too loud, for one of the wardens asked us to moderate our voice. My dad apologised: “Sorry, but we have just come from our village today, and we are not used to the capital ways. We talk like this to the pigs all the time”. Luckily, the man smiled at this comment, as you can’t but do when dad deadpans his awkward jokes. It was the second time we were told off, for someone else had warned us earlier not to get too close to the exhibits. “They are going to kick us out”, we laughed, before moving to a wonderful painting of a lady in yellow.

We talked about how difficult it is to get a true likeness in painting and discussed several theories about what it is that achieves the recognition effect, whether it is colour or design that does the trick, the age-old question. We settled for the judicious use of shadows and hue as the key to it. An elegantly-dressed lady who was overhearing us said she had never thought about it in those terms. She asked us to explain it further for her and my father kindly obliged, in his loud voice. The warden that had told us off before came to listen to him, but he refrained from a second reprimand. We felt vindicated. He probably thought my dad was a Picasso-like genius, unconcerned about gallery-visiting etiquette. He certainly looked the part, with his elegant black coat and his flat cap. We laughed heartily like two naughty boys as we left the exhibition.

We had such a good time that, as we returned to Barcelona and got off the train at Sants, even though it was late and we were tired, dad insisted on taking us for one last beer at the station bar. He clearly wanted to hang on to the happy days shared, as it is often the case when one has had great time in good company.

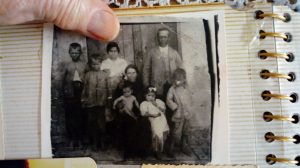

That last day in Barcelona three months before Madrid, over lunch, I asked my father about the origin of his maternal surname, “Expósito”, which in Spanish means literally “foundling”,. It was the surname given at orphanages to children that had been abandoned and taken by charity. I had always assumed that it would have been given to a distant and forgotten ancestor, but it turned out that the unfortunate child was my great-grandfather . My aunt Regina from Bordeaux was the first to tell me the story, when we met at a family reunion that took place there in April 2014. Since then, I had heard different versions from other sources but, as my aunt Regina is the eldest of the eight grandchildren that my great-grandfather had, I would tend to believe her account as the truest one, for she had had some first-hand knowledge of that man, after whom both my father and I were named.

The story that I heard in Pozoblanco from my cousins there was that our great-grandfather Rafael, had been born out of wedlock from a schoolteacher in the small village of Villaharta, high on the sierra that separates the Pedroches valley, of which our native Pozoblanco is the capital, from the city of Córdoba and the rest of Andalucía. For obvious reasons, the identity of this lady is not known. Whatever the family knows, it must have been told hush-hush later in life, put together from rumours spread at a time when gossip was a form of entertainment in that rural area. In the absence of radio and TV, people would gather round campfires to tell each other stories while caring for the Iberian pigs, cows and sheep, or tendering to the olive groves that made up the wealth of the region.

Nothing is known of the man who got the schoolteacher pregnant, if that was indeed the story, but the fact that she left the poor hapless child at the door of that rich landowning family, may indicate that the child’s father could have been the young master of that house, el “señorito”. Sexual affairs were certainly widespread for men of that standing in those days. This theory would perhaps be supported by the fact that, although the family took the boy into the family, they did not give him their surname, as this would have amounted to admitting guilt. Hence the “Expósito” that would be passed through the generations.

But my aunt Regina said that she had never heard that story before. For all she knew, her grandfather was adopted straightforwardly from the town’s orphanage by a relatively well-off farmer couple who could not have children of their own. This is a less romantic version, and arguably more plausible, but it leaves us to wonder why would such a loving couple not give their own surname to a lawfully adopted child.

My great grand-father Rafael married first a woman whose name nobody seems to remember, although it should be easy to find in Pozoblanco´s municipal archives. He had two children by this first marriage: my dad´s aunt Filomena and her brother José, who died during the war at Puertollano´s hospital, a small town across the border into the province of Ciudad Real, the fabled La Mancha of Don Quixote´s fame. He died of what my father called “purgaciones”, which is basically the clap, although it could also mean any venereal disease at a time before penicillin became widespread and prevented such infections from becoming deadly. According to my dad, he had no politics and was just fighting because everybody was forced to do so, for whatever side you had been caught by the war.

Everybody in the family remembers their aunt Filomena as a kindhearted lady, warm and very close to my grandmother Josefa, who became her half-sister after her mother died and my great-grandfather Rafael married again. His second wife was called Ana Fernández and with her she fathered four more children: my grandmother Josefa, two more girls called Asunción and Tránsito, and a boy called Alonso. Out of those, aunt Asunción and uncle Alonso (as my dad and his siblings always called them) were somehow present in my childhood, although by name only, for I never had any direct contact with them.

All I can remember is that when my cousins visited Pozoblanco, they often stayed with that legendary tía Asunción. According to my dad´s account, she and her children seem to have been the only self-interested of the four siblings. It was her and her descendants who kept the house and whatever land Rafael had owned, although by then all the wealth of his adoptive parents would have been rather depleted, shared as it would have been by all the descendants. In any case, they all seemed happy for tía Asunción and her children to get whatever inheritance there was. They held no grudges and moved on without acrimony.

My dad told me that, by unhappy coincidence, Rafael would go to die in the same hospital in Puertollano as his son had done, and during the Civil War too. One can only wonder about the feelings this man must have gone through. If he was anything like me and my own dad, with whom we share name, I expect he would have shed a tear or two at the unhappy coincidence.

Both dad and I cry at the drop of a pen. I remember dad in tears as he listened to his old flamenco cassette tapes or whenever guitarist Paco de Lucía played on the TV. My mother, who was made of sterner stuff, always mocked him gently when this happened: “ya está tu padre llorando con sus músicas”, she would say (“there goes your dad, crying again at his music”). I was always very impressed with that acute sensitivity to music of my dad´s, so “unmanly”, except that flamenco singers and dancers, unlike rappers or others, have never had a problem exhibiting their bodies or expressing their emotions in songs.

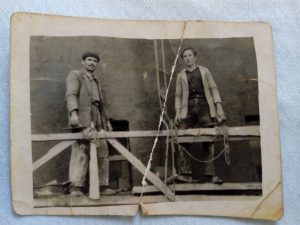

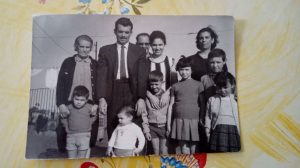

My family moved to Barcelona in 1964, when I was just a couple of months old, but my father had arrived earlier, in 1962, alone, like so many men from the south. My mother had stayed in Pozoblanco, taking care of her mother, who had gone blind as a consequence of the cancer that would eventually kill her. Dad’s sisters were by then all living in the Catalan capital and so was his own mother, my grandmother Josefa, who moved with my uncle Manolo, the younger of my father’s siblings. When he arrived , he found a job working for a boss who recruited builders, the job he had trained for after finishing his military service in Seville.

The Spanish economy had been kicked-started by the development plans implemented by General Franco as a result of the agreements he sealed with US President Eisenhower in September 1953. In exchange for allowing the settlement of four US military bases across Spain, the country would receive economic aid, thus throwing a lifeline to the regime, whose dream of self-sufficiency had had catastrophic results.

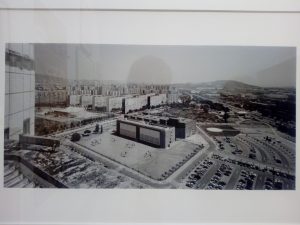

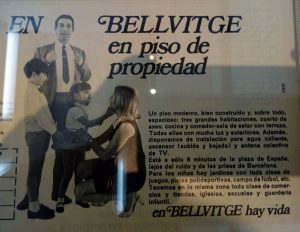

One of the pillars of that development would be a construction boom in cities and areas ear-marked for tourism development. Dad was one of an army of young women and men from southern Spain who left behind their homeland for the growing poles of economic growth where the new cash was invested.

That first boss my dad’s paid him 1200 pesetas a week, at 12 pesetas per hour. According to my dad, he was a total moron. He was from the Catalan province of Gerona and, like so many people in northern Spain, held Andalusian workers in poor regard, if not plainly in contempt. He claimed they were stupid, lazy and incompetent, although it seems he was pretty useless himself. Whenever he turned up at the work-sites, he would criticize and question their building techniques. He started fiddling with the cords they used to erect walls and meddling in all sorts of unhelpful ways.

He also had a dim-witted nephew whom he had appointed as works supervisor nevertheless. Dad was unhappy. It was then that he would chance upon an old friend from the days when he had worked in Puertollano, in La Mancha. The brand-new El Corte Inglés department store was then being built in Plaza Cataluña and dad had stopped to watch with professional curiosity. He was spotted by Pedro, this old pal, who was working on the site. They were very happy to have bumped into each other and, as dad told him of the bad conditions under which he was employed, Pedro introduced him to his own employer and, on the strength of Pedro’s recommendations, he was hired on the spot. He was offered 18 pesetas per hour instead of a meagre 12. So my father went back to the nasty boss from hell and his short-witted nephew and took great pleasure in not only quitting them unceremoniously, but also taking along with him all the rest of the squad, who also applied to work at the department store site and were given jobs there. It served him right, that monstrous idiot.

My parents had first met while my dad studied at Pozoblanco’s Salesian school. This had been founded in the late nineteenth century to provide Christian education for the middle classes and selected bright students from the peasantry. It had an ultra-conservative ethos, teaching an interpretation of Christianity to counter the threat of the irreligious socialism that had spread quickly throughout the country since the foundation of the PSOE (Spain’s socialist workers party) by Pablo Iglesias in 1879. That education consisted in teaching boys the three basics – reading, writing and arithmetic – at the simplest level, together with hours of Catholic doctrine. As my dad put it, he learned there between “poco y nada” (between little and nothing). Girls of the working classes were not deemed to need any instruction whatsoever other than the basics of being a housewife and an obedient wife. Thus, my mother and my aunts did not learn to read and write till adulthood, when they took time to go to night school.

The Salesian school of Pozoblanco was, and it still is, in Calle Andrés Peralvo, just across the road from where my mother was living at the time. She must have been 12 or so at the time and she hang around in a little square nearby, playing tag, hide and seek, and other games. My dad remembers there was a somewhat dim-witted girl that used to play with my mother’s gang. It was she, apparently, who got them in touch, one imagines in that age-old fashion in which youngsters have expressed interest in each other throughout history: by the use of a go-between that seemingly acts independently, although more often than not has studiously been instructed by one of the would-be lovers to convey the desired message. My dad says that back then he did not have any interest yet in the mating game, though I take it that he was appreciative of my mother´s beauty and deportment. Sadly, my mother died long ago and I can´t say whether she found him handsome or not then but, knowing how much quicker girls mature at that age, and given that my mum was two years older than dad, it is likely that she may have set her eyes on him in those innocent days while playing in the little square opposite dad’s school.

When eventually he developed those instincts in the joys and pitfalls of courtship, he got himself a girlfriend from a nearby village, Añora, whom he courted for three or four years. My dad said with cruel honesty that he did not really like her and would have left her sooner, but that he felt a sense of duty and did not find it in him to leave her for a long time. With equal cruelty, my mother and her sister, my aunt Adora, and this confirm my theory that mum had already set her eyes on dad, would make fun of him for going out with a girl that was somewhat bowlegged. They did so whenever they came across him and his gang of male friends walking down “el paseo”, the Sunday evening stroll that was and it probably still is, the main social occasion in small towns across Spain. In the event, it was the long period of compulsory military service, what would break my father’s vows to the girl from Añora, making it easy for him to drop the relationship in a diplomatic and smooth way.

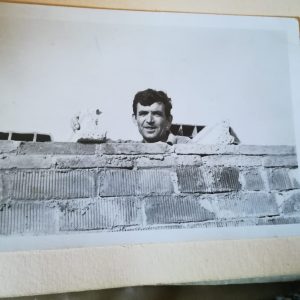

When dad was released from military service and returned to Pozoblanco, he was ready to settle, anxious to start life on a good footing. That´s when he took to construction, a profession that everybody knew at the time had a good future, given the prospects opened to the economy. The phenomenon of mass migration from villages and small towns to the cities required vast new housing estates and thus the skilled workforce to do so. There were also gleaming office towers to build, hotels, motorways, airports and seaside promenades; all the infrastructure needed to develop and modernise the country.

The men in grey advising the dictator’s government did not see a viable economic future in agricultural areas like the Pedroches valley and so, all that valuable human capital was encouraged to migrate to the new centres of development in the cities of the north and along coastal areas, where tourism was just about to boom. Investment was localised, the agrarian reform which had been the eternal question in southern Spain throughout the nineteenth century was to be solved not by land redistribution as dreamed by the socialist party, but simply by those ill-treated and abandoned to their fate workers voting with their feet and just leaving everything behind to move to Barcelona and Madrid, to Valencia and Bilbao and further afield to France, Germany or Venezuela.

It is when he returned to Pozoblanco after his army stint that my dad met my mother properly and got to be engaged to that girl that he had seen playing in the square when he came out of school. It was at the annual olive harvesting season, a job in which the whole town of Pozoblanco was involved. My mother used to tell me of how they dreamed of the money they would earn at the end of the season, only to be disappointed when payday came and after all that hard work in the freezing fields, once maintenance and food were deducted from their wage packages, they were left wondering why they had bothered at all.

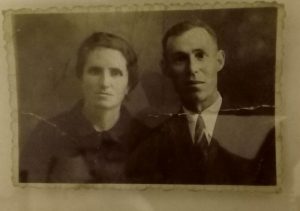

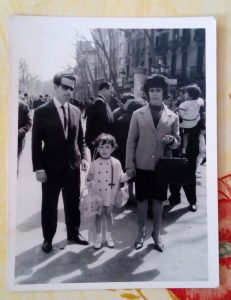

Still, they were young and made the most of their lives. My dad was handsome and popular with the girls. My mother was pretty too. They fell in love and began to dream of a future together. They courted for four years before getting married, as it was the custom at the time. My dad jokes that, if they finally married, it was only because my mother’s mother urged her to do so. According to dad, mum was always one to agonise about any decision and she seemed to be perfectly comfortable sitting on the fence. I guess it was because she was wise and knew what lay ahead for her: a life of permanent anxiety with a family to bring up, in city far from everything and anyone she knew. No wonder she was happy sitting on the fence.

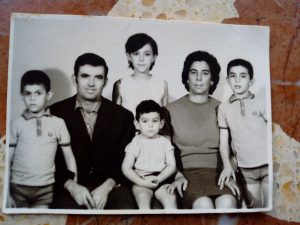

But needs must and so she finally took the plunge. My parents married in 1959 and in 1960 my sister was born, followed by my older brother in 1962, myself in 1964 and then my youngest brother, the only truly Catalan one, as it would become customary to say in the family, for he was the only one of us born in the city which we would call home: Barcelona. I was just 40 days old when, lovingly held in my mother’s arms, we boarded the legendary “sevillano” train, which covered the journey from Seville to Barcelona in twenty-eight hours. I’m told that, once past Valencia, most of the travellers stuck their noses against the windows on the right-hand side to see the sea for the first time. Magical.

The facts of our arrival in Barcelona are clouded in legend on my mind. They reach me in fragments of conversations heard throughout a lifetime of family visits and memories from siblings, cousins and other relatives. They are like pieces of a puzzle that I try to fit together, a task that can only be approached gradually, as some won’t fall into place until others have done so before. There is first a flat at 161 Calle Diputación, near Calle Balmes, a very central location, before that later one in Calle Ávila, in the Poblenou district.

The first members of my dad’s family to move to the city had been my aunts Felipa and Manola, who arrived in Barcelona’s Estación de Francia in 1957. My aunt Felipa’s fiancé, who would later become my uncle Bartolomé, a carpenter by profession. He had found a job at a workshop in the city through a friend who had done military service with him in Seville, a man called José. This workshop was in 6 Calle Tantarantana, next to where he lodged in number 8 of the same street. That was in 1956, when he was already engaged to my aunt Felipa. It seems that, once in town, he got involved with another woman and the news reached my aunt’s ears. Not one to take things lying down, she and my aunt Manola rushed to Barcelona to ensure that order was restored. The mission was successful and my aunt Felipa would marry my uncle Bartolomé a year after, settling permanently in Barcelona. My aunt Manola never went back to Pozoblanco either. She would find soon a husband in town too. The flat in 161 Calle Diputación was owned by two sisters, Señora Rosa and señora María, who rented rooms to make ends meet. After marrying, my aunt Felipa and my uncle Bartolomé lived there for a while. It is also there where their first daughter would be born, my cousin Pepa. In the next few years, that address would become the ground zero for the members of the family who gradually left their hometown to find a new life in Barcelona.

My aunts arrived at Estación de Francia in 1957 where they almost fell into the hands of the sinister “inspector” Grabado, a corrupt policeman that self-styled himself as unofficial immigration officer, controlling the wave of immigrants from the south. He waited everyday for the train from Seville to arrive and asked all the new arrivals for their papers. If they could show a work contract, he would let them go: if not, they were sent to a detention camp for a few days and then sent them back to where they had come from. Such control was a relic from the postwar times, when all movements were rigorously controlled as the dictatorship staged its brutal repression campaign against anyone who had been involved with the Republican side. My aunts escaped inspector Grabado’s zeal because my uncle came to meet them and thus he was satisfied they had someone to take care of them.

In 1961, my grandmother Josefá, dad’s mother, also moved to Barcelona. She came with her younger son, my uncle Manolo, and they also lodged at 161 Calle Diputación, where my dad would join them too in 1962. My grandfather Manuel had died in 1955 and my grandmother did not see any point staying behind in Pozoblanco, so she came to join her daughters. She would soon rent her own flat in Calle Ávila in Poblenou, where we would live in March 1964. This used to be the industrial district of Barcelona, known as the “Catalan Manchester”. The building still stands, as indeed still does 161 Calle Diputación.

It is difficult to imagine the exhaustion and stress that my parents must have endured in that long train journey in April 1964. There is a very famous photo taken by Catalan photographer Xavier Miserachs showing a group of southern immigrants that have just arrived in Barcelona. They are in Passeig de Gràcia, whose elegance contrasts with their scruffiness. They must have just got off the train after the long uncomfortable journey. The group, formed by two men and one woman, are carrying their battered heavy suitcases as they look at the camera with an expression that shows both mistrust and defiance. It is a good image. It captures the mutual incomprehension between the bourgeois photographer and the newly arrived. That incomprehension would last some years and, to a certain extent, it never really went away in spite of the best efforts on both sides. That arbitrary prejudice against Southerners of my dad’s first employer still persist in the mind of many. However, my family’s integration in Catalan society, like that of most families, has been a great success thanks to the generous spirit and the faith in progress that drove the reconstruction of Europe after the tragedy of war.

So that’s how my father came to find himself coming in and out of hospital in Barcelona that Christmas time in 2017. As I write this today, he’s back in hospital, fighting for his life. Let this be an homage to him and to all those brave women and men who left their homeland and build a better future for all of us.