East meets West

Headington, Oxford, is now a pleasant middle class spot but was once associated with the washerwomen who did the laundry for the colleges of that most famous university town. Legend goes that the prices of properties were once calculated by the metres of bed sheets one could spread to dry in the back yards.

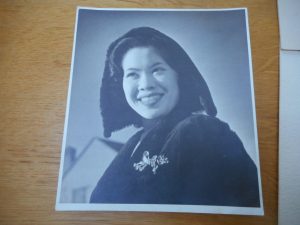

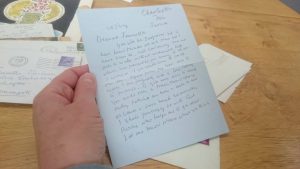

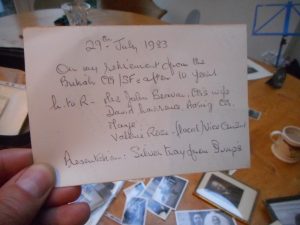

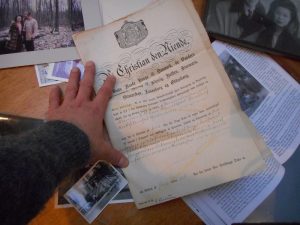

I am here to meet Louisa and hear all about her aunt, Janetta Poulsen, an elegant and becoming lady who had a long, eventful life. Now sadly gone, all that is left of her colourful world -a set of letters, some pictures, a few documents and such like- has been lying dormant for years, tucked away in the small pretty suitcase she used for weekend trips, gathering dust in a lost corner under Lou´s roof.

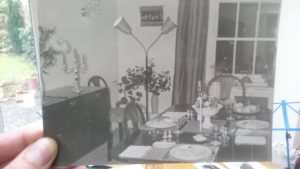

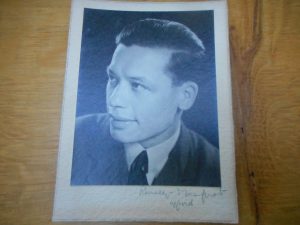

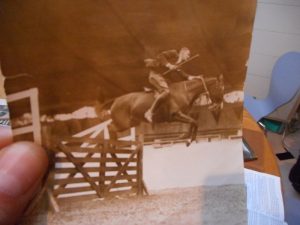

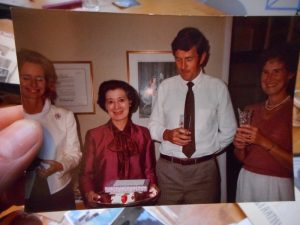

Louisa’s living room is presided over by an impressive painting of Janetta, looking dazzling with her delicate half-oriental features and her chic green dress. She was painted by Duncan Grant, a famous artist from the Bloomsbury set with whom Janetta had once had a brief fling. On the shelves in that living room there were other beautiful objects that had also belonged to her aunt: fine Chinese vases, old photographs and pieces of furniture, the flotsam and jetsam that we leave after we die. Louisa points them out to me as she gives me some quick nuggets about her aunt´s life as a kind of “hors d’oeuvre”.

Louisa is understandably somewhat apprehensive as to how I am going to deal with such private material and I do my best to reassure her. “I will write the truth”, I say, “whatever that is, seeing that for most of the story you are going to tell, you are once, if not twice removed”. She nods and we discuss briefly the nature of memory and truth. Louisa seems to be put at ease. “Well, all I can say” she concludes to my great delight, “is that Janetta would have loved to be here today because she loved talking about herself, but she hardly ever told the whole truth”.

I knew from that moment that our session was going to go well.

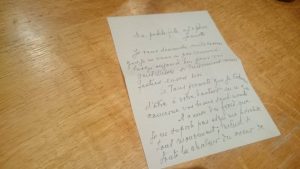

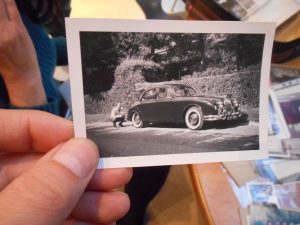

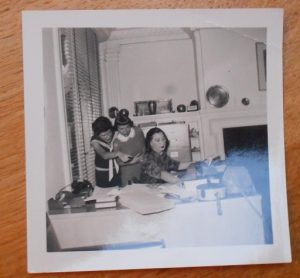

As she serves me a cup of tea, we set to the business at hand, rescuing from the jaws of neglect the story of Janetta Poulsen. Her life had intersected with key moments of the sad history of our ever-embattled lands. Louisa takes some photos out of the suitcase and spreads them across the table, as if they were tarot cards, and begins to tell me what she knows or can recall about each one, making educated guesses when hard evidence has been lost. I listen and take mental notes to eventually write this story, which will take us across the world, from London’s old Chinatown in Limehouse, a few miles down the road where I live now, to Japanese-occupied Hong Kong, then sail back to England to reach a country exhausted by rationing and bombs, where she won’t stay long, moving to Denmark and then on to America, keeping pace with the times. We follow her trail as she glides across the globe, determined to leave behind her woes.

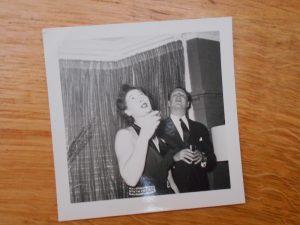

Throughout the afternoon, I hear of friends and lovers, admire pretty dresses and attend elegant cocktail parties at embassies and luxury flats. The cast is impressive in the lady´s play: there are Danish counts, captains of industry, Hollywood stars, celebrated painters who fall madly in love with her and then despaired as she treated them with disdain. We read letters of men who walked under her windows, searching for answers to the same questions that I will pose to them upon my return to London later that Sunday afternoon, when I went to Eaton Square, where the lady in question entertained in style throughout her London years, living the life of privilege and charm that she built for herself, forgetting her humble origins as she partied with her celebrated neighbours downstairs, Vivien Leigh and Lawrence Olivier, with whom she used to share some gin over a game of cards.

The story of Janetta starts in two different parts of what was the British Empire. Her mother, Beatrice Marie Shawn was the daughter of a butcher in London´s East End; and her father a Chinese man of obscure origins, who legend says arrived in Limehouse in 1912, carrying a bundle of silks to sell. We know little about the fate of those silks, but he must have disposed of them successfully enough to make the money needed for him to set a gambling den in Poplar neighbourhood. There, a small community of sailors from Shanghai had established itself since the end of the nineteenth century, around the Pennyfields area, a stone throw´s from Poplar High street, where Marie´s parents had their butcher´s shop.

We don’t know either how they came to meet and fall in love but such proximity surely offered them plenty of chances. Perhaps Shung was a customer at Marie´s family shop or maybe she walked every day past his gambling joint. Who knows? But meet they did, and in 1917 they married at St Peter´s Anglican church in nearby Garford Street, built between 1882 and 1884 out of a small mission catering for the spiritual guidance of what was then a rough part of London. Like the rest of the neighbourhood, St Peter´s is long gone. It was pulled down in 1972, when the docks became redundant as new technologies got rid of stevedores, and the port of London was moved to Felixstowe. This erasing of tracks would suit Marie and Janetta very fine, for they left the East End with the firm intention never to look back.

The marriage of Marie and Shung could not have been approved by her parents, and must have been frowned upon by all. Louisa quickly let me know that was so. Those were not politically correct times and multiculturalism wasn´t yet the selling point of London that it is now. Shung is said to have sported the classic pigtails and to have been always dressed in his Chinaman silks, at a time Sax Rohmer started publishing his series of books about Fu Manchu, a supervillain that stereotyped the yellow peril fears that had spread throughout the East End.

But Shung and Marie seem to have understood each other well and the marriage produced four daughters and two sons. The four girls, Janetta, Beatrice, Marjorie and Enid Ann, would bloom into four beauties of exotic mix-race looks, but only one of the two boys survived, Len. Whatever exaggerations and xenophobic slurs may have been behind the stereotype of Fu Manchu, and sure there were quite a few, there must have been a grain of truth in those stories of opium and gambling dens, for that was the trade where Shung and Marie would thrive.

Sometime in the late twenties or early thirties, however, things would take an unexpected turn. Shung was the victim of a vicious attack, possibly by some disgruntled punter to whom he owed some sum or any other obscure affair. He was dealt a hard blow on the head, according to family legend, in the middle of one of London´s infamous pea-soup fogs; it left him severely disabled, unable to remember what he did or who he was. For a while, Marie continued the business and took good care of him but, to everyone´s distress, he vanished one day never to be seen again. Marie was left to fend by herself, cut from her own family, with his young boy and her four girls of marriageable age, like a mother in a Jane Austen novel.

She kept working hard, though, and, a few years before the Second World War broke out, she put some money together and sent Janetta to China, with the pin in-a-haystack mission of searching for whatever Chinese family of Shung´s remained there, to try to find out whether he had somehow made his way back there.

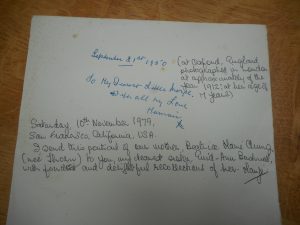

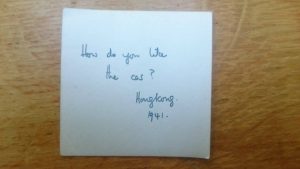

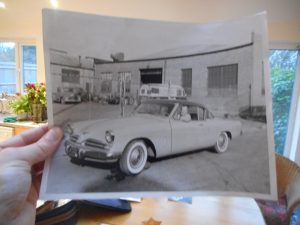

Janetta arrived in Hong Kong, then still Crown colony of the UK, but could not go much further as the Japanese invasion of China left her stranded there. It does not seem, however, judging by some of the pictures we have of those years, that she had a hard time of it. We have, though, a picture where she poses, glamorous and playful, seductively sitting on the bonnet of an automobile. On the reverse, she wrote in her neat hand; “How do you like the car? Hong Kong, March 1941”. She looks so lively and beautiful that it is difficult to take notice of any car. But then, the Japanese

invaded the colony itself. Then Janetta was interned in the notorious camp where the Brits that could not be evacuated or escape were sent, in the grounds of a secondary school in the peninsula of Kowloon. There is little evidence of those dire straits of hers, as she was never one to dwell on unpleasant episodes.

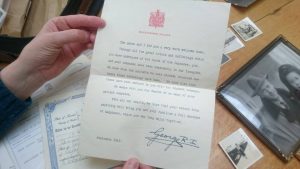

Being held in Kowloon´s prisoners camp could not have been fun at all but, never one to care much for unpleasant events, whatever hardships our heroine underwent, she kept them to herself. However, a letter signed by His Majesty King George VI, acknowledges her sufferings for king and country.

For almost four years, the Japanese occupied Hong Kong, a time in which God only knows the vicissitudes our lady endured. But nothing lasts forever and so, as the war ended, she boarded a ship and returned to Britain, and it was on that long cruise back to where she had left mother and sisters, that she met the man who would become the rock to which she would tie her fortunes for the rest of her life.

He was a rich Danish businessman, a company executive for the Tuborg brewery, of arresting looks: blonde, slim and handsome. One wonders what he was doing on that passage to Britain in 1946. Whatever the reason, the fact is that they met as the ship made its way west, and by the time they disembarked in Southampton, they were in love and would marry soon. He took a post as representative in Britain of the famous Danish brand, a job which was going to be rewarded with a flat in Copenhagen that the couple would enjoy for life. It was an elegant place, like so many others where they would live as they embraced with great relish the new world order that came out of the ashes of the war.

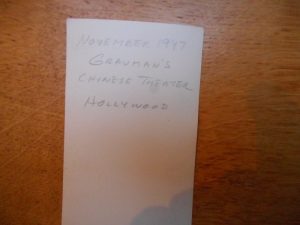

The American century was just about to gather speed and Janetta was determined to embrace the excitement of it all, living the fifties and sixties to the full, moving to Los Angeles, where her dashing husband, Henning Poulsen, was promoted when Pepsi-Cola bought Tuborg. What could be more emblematic of the times that were to come? The substitution of privilege of birth and ownership of land for the new aristocracy of consumer goods and well-recognised brands: the American way of life. Not for Jannetta the depressing England of the post-war years, with its grim ruins and dusty hats. California, there she went, following the sun.

The other three sisters would eventually end up on America’s Pacific coast too. Beatrice would settle in Los Angeles soon after the war, having married a charming American GI of Chinese origin, who had been posted in Oxford during the war. Marie and her children had been relocated to Oxford to save them from the bombs falling on London’s East End. Marjorie, the third girl, would soon follow her sister and take a post at the British consulate in San Francisco, where she lived until her death.

Louisa’s mother, Enid Ann, the youngest of Marie´s girls, was the next to head to the New World. She married an Oxford physicist employed at Aldermaston, where the UK nuclear deterrent force was being developed, but soon tired of the dullness of provincial life in post-war England, with its endless rain, food rationing and lack of modern comforts. The couple moved first to Kingston, Jamaica, and then to Victoria, on Vancouver Island.

There, Louisa grew up until she won a scholarship for the Royal Ballet school in London, where she was born and her aunt Janetta had returned, as Henning was posted back in Europe. Louisa would then forge a keen friendship and long-lasting affection for Janetta, who would eventually leave to her, among other things, the pretty weekend suitcase from which we invoked the lady’s spirit in that corner of Oxford on a Saturday afternoon.

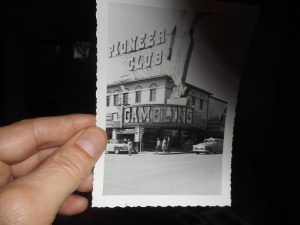

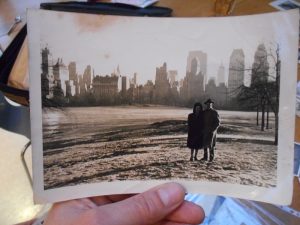

She had lived a charmed life in L.A, mixing with those captains of industry and Hollywood grandees, that formed the aristocracy of the brave new post-war world. There are Christmas cards from Joan Crawford, married to the head of PepsiCo and so best friends with our golden couple; there are also pictures of happy days with Marie visiting them in Sausalito, enjoying nostalgic fish and chips by the Pacific Ocean; and there she is again, Janetta, having a laugh with her colleagues at the British consulate in L.A, where she took a post dealing with their accounts, having inherited from Shung his way with numbers… and casino gambling; there they go travelling about: New York in the snow, sunny California, Las Vegas and the beaches of Trinidad, cocktails and champagne like there´s no tomorrow.

But then tomorrow did come. Gradually, that golden age came to an end and the couple’s bright sun began to set. Back in London, where Louisa met them as she came to study dance, and later in Copenhagen where Janetta would retreat in her late years, the perfect mirror started to show some cracks. There were stories of infidelities by the handsome husband and a brief period of separation. She went to work as housekeeper for a Danish aristocrat related to the Queen of Denmark, with whom she started an affair that was to be short-lived, for he died soon of a heart attack. She came back to her husband and, for a while, they lived as happily as they could, but drink and disillusion had somehow set in, and nothing was quite the same as it had been. It is then that Janetta met Duncan Grant. Again, according to what she said, as they both were coming out of the British Library. He asked her to pose for the portrait that now hangs at Louisa’s Oxford living-room and, in those sessions, he fell head over heels for her beauty and extraordinary charm. Yes, the old master got it bad but Janetta’s mind was not in it. He was then old, infirm and in need serious care. He lived in Surrey with relatives or some old friends and Janetta did not fancy disrupting that domestic setup, getting perhaps trapped in family squabbles and taking responsibilities for which she was not sure she was well-equipped.

Age was catching up with Janetta too. Soon after that, Henning died, forcing her to abandon her elegant flat in Eaton Square and retreat to Copenhagen, to the safety of that rent-free flat they had been granted for life, and to a post at the British Embassy in Denmark, working again as accountant for her Majesty’s legation. So, the old painter was left behind, mourning her desertion. His increasingly plaintive letters – “I walked under your windows again but they did not answer my questions”- sent to the Embassy address, indicate she never gave him her private one. Janetta adapted again to her new life the best she could but her best days were clearly behind her. One day, driving with a good old friend, they jumped a level crossing and were hit by a speeding train.

Miraculously, they both survived though Janetta suffered a brain injury that would leave her infirm until she died. Somehow, her colourful life reached the attention of a BBC producer who convinced her to appear in a moralistic programme about what happens to a party girl when the music stops. She relished her moment in the sun but Janetta’s mind wasn’t seriously in it. She wasn’t into nostalgia, as we know; she had never been one to look back, whether in anger or in yearn.

She briefly returned to Oxfordshire, to an old people’s home paid by the BBC in exchange for her life-story but Louisa knew she would never adapt, and sure enough, she soon went back to Denmark where she would live her last years in relative comfort, cared by friends and relatives until the moment where she died, when she left her little archive of experiences to her devoted niece, Louisa, who kept it all in her attic until the time came to tell this story and bring the old girl back to life again.