The Poet’s Call

When does a story begin and when does it end? Did this story begin the day I travelled west, crossing like an arrow the Salisbury plain on the way to the mouth of the River Dart? Or did it begin the following morning as I set off walking along the lane from Galmpton’s Manor Inn? Did it do so almost twenty years ago, before Amazon and even the internet, when a good old friend asked me if I could find for her in London “Armada”, the book she couldn’t buy in New York? Or was it when the poet himself wrote his collection, as he confronted his mother’s death?

Then again, it could be equally when, second time round, I read it myself, as my own mother lay dying in a hospital bed; or equally when another friend set in motion the exchange of emails that intrigued the poet and led to an invitation to visit him. Stories start and end serendipitously at any given point we choose for them. They go on to entangle us in a narrative where “I” becomes “we”.

There are stories that, like life itself, one does not know how they began but one does not want them to end. This is the story of my visit to Brian Patten, a man after my own heart, arguably the greatest poet alive in England today, with whom I shared an afternoon by the banks of the river Dart, where a ferry braves the tides and children fish for crabs. One should always approach poets by boat.

I set off in the morning from my inn at Galmpton, past the cottage which I would later learned had been Robert Graves’ refuge when the Spanish Civil war forced him out of his Majorcan retreat. There´s a narrow country lane to Greenway, Agatha Christie’s old home and the point where a boat would cross me to Dittisham, where the poet lives. I had barely advanced half a mile when a little coach came towards me, occupying almost the whole lane with its fat body. It was the “Miss Marple”, taking tourists from the train station to the celebrated murder mystery writer’s home. The driver assumed I was also a visitor on my way to the house and he stopped to let me on board. As I took my seat with the other tourists, I felt a bit like I was on a school-trip, merrily driven down under a canopy of summer leaves with the glimmering waters of the estuary of the Dart on our right and, to add to the enchanted dream-like scene, an old steam railway line running parallel to us.

The passengers, mostly French-speaking Belgians, looked at me with curiosity, like kids on the first day of school, sizing up their new mates, or like characters in a whodunnit trying to figure out who the murderer will be. After a short ride, we arrived at Greenways’ gate where the tourists’ path diverged from mine. They walked up towards Agatha Christie’s elegant home and I down towards the quay where the ferry crosses the Dart to the little village on the other side, the appointed sands, as Emily Dickinson may say. Dittisham.

The water was calm, the sky overcast. The boat made its way across to the wharf where people were throwing fishing lines and children little buckets to catch crabs which, once trapped, were sent back to the river, their lives spared by life-conscious parents, mindful of teaching children respect and love for all the creatures in the world. I walked along the jetty towards a street between the Ferryman´s Inn, a pub brightly painted in pink, and the Dittisham Anchor Stone Café, with a board outside boasting the best ale and fish and chips in the world.

A steep path led me from the shore to his home, a modern building with a pointy roof, balconies and surrounded by a garden on a slope. I rang the bell and, there he was, greeting me with a broad smile, the poet himself.

“I recognise you”, he said, probably from some videos I had posted online reading his poetry. As it was a Summer day, warmish, he asked me to go around the house to a patio area at the back, where he would bring some drinks. I did and soon he reappeared from inside, sliding open a large French window from which I peered into a comfortable living room, with high ceiling and many paintings hanging on the walls.

As it was just past midday and too early to drink, I expected he would offer me tea, but he mischievously looked at me, winked and asked whether I would like a San Miguel, pronounced with a u, like most English speakers do. I said I’d very much like one. and he went back into the house to fetch a can of San Miguel for me and a London Pride for himself.

“Beer at midday! You are a man after my own heart. ”, I said. “That’s what we do in Spain, the aperitif, as it is called. I thought here it was very much frowned upon to start drinking so early”. The poet gave me again his smile of naughty school boy and said it was past midday so that was alright.

The view of the estuary was a bit obscured by some trees. I suggested it must be better in winter when the trees lose their leaves, but the poet said it was good all year round, that he likes to see the water between the leaves too. I agreed, for one can´t possibly have too much of the combination of sea, sky and trees.

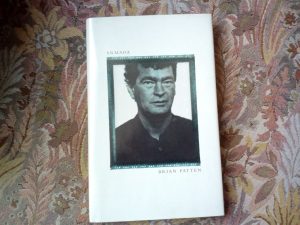

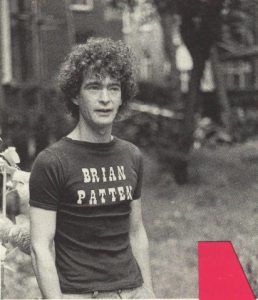

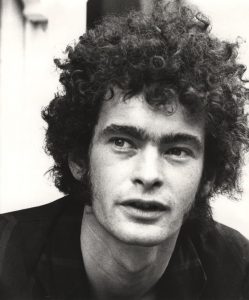

The poet is seventy and, according to him, recovering from a health setback. However, one would not be able to tell, judging by his good humour and good looks, that he is anything but in rude health. He still has his trademark curls still intact, defying age, not much different from his appearance on the cover of his books. I had some concerns the night before about how the meeting would go, fearing that I may look a bit silly at my age, acting like a teenage fan of a rock star, appearing at his door all starry-eyed and naif with my autograph book.

I feared being somewhat disappointed for, as they say, one should never meet one’s heroes. But I know his poetry well and said to myself that a man who writes so well and in such depth about the extraordinary experience that is so-called ordinary life, would surely be a man with whom I’d have a lot to share. I was not to be let down.

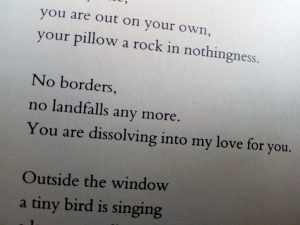

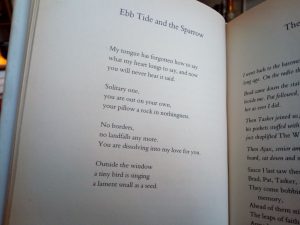

I started by saying it was a great privilege for me to meet him, but he stopped me on my tracks. “Please, no”, he said. “The privilege is all mine”. I insisted it was, and told him about my mother’s death long time ago, and the special role his poetry played then. I was reading Armada as I kept vigil by her hospital bed and identified with his account of how he had felt. The verse that I had just read when she gave her last breath was: “You dissolve now in our love for you”. Translated into Spanish, it is now the epitaph on my mother´s grave.

His words spoke deeply true to me again, a few years later, when my mother’s sister died, my aunt Adora from Alicante. As a homage to her and expression of my feelings about her passing away, I posted on my Facebook wall another poem from his “Armada” collection: Betrayal. I was moved by that poem’s poetic call to arms, feeling an urge to give a voice to a vanishing world; to find and sing the beauty hitherto unsung of those lives that quietly disappear, ignored by all, consigned to the skip of history.

I sympathise and identify with him, a working-class hero, as John Lennon, his fellow Liverpudlian, would say. It is not easy to rise over the impediments such background imposes on you. I admire how he went on to develop a language of his own to express his fears and his hopes, discovering the poetry that lies buried in shoe-boxes full of old black and white pictures, holding the experience of those doomed to oblivion.

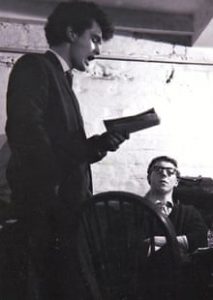

“How did you become a poet?”, I asked. It all started by chance, the poet said, at secondary school, when he wrote a composition that was praised by his teacher for being particularly well-written, too good for what was expected from someone like him. They did not quite believe it could have been his own work, but so it was, proving all their prejudices wrong. As a result, he was moved to his form’s top set. Sadly for him, as he said, giving a hearty laugh, for it involved working hard from then on, compared with the easy ride he had enjoyed at the bottom set. The poet does not remember what it was about, but on the strength of that text new horizons opened, a new sense of possibilities, a certain ambition perhaps.

He started independent readings of literature works from far afield. He discovered the poetry of Baudelaire and Rimbaud, of Lorca and Neruda, with whom he would later share a platform somewhere in England when the great Chilean poet came to read his work and the poet was invited along other poetical young guns to read his own work as a kind of supporting act. “The token youth”, he said, showing his best self-deprecating smile.

Sadly, this story of low expectations from the working classes sounds familiar to me. I remembered my shock when I started teaching at a South London school. Kids divided by ability into three different sets, condemning to ignorance those at the bottom end, the teachers’ assessment becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy. I told the poet about this experience of mine, how the kids in my lower set were puzzled at my insistence on teaching them at all: “but, sir, we are the bottom set. We are not supposed to do any work”. The poet nods. Terrible state of affairs.

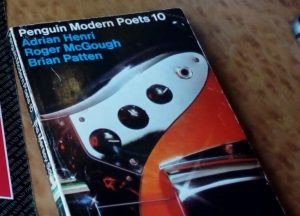

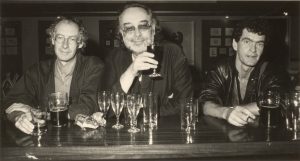

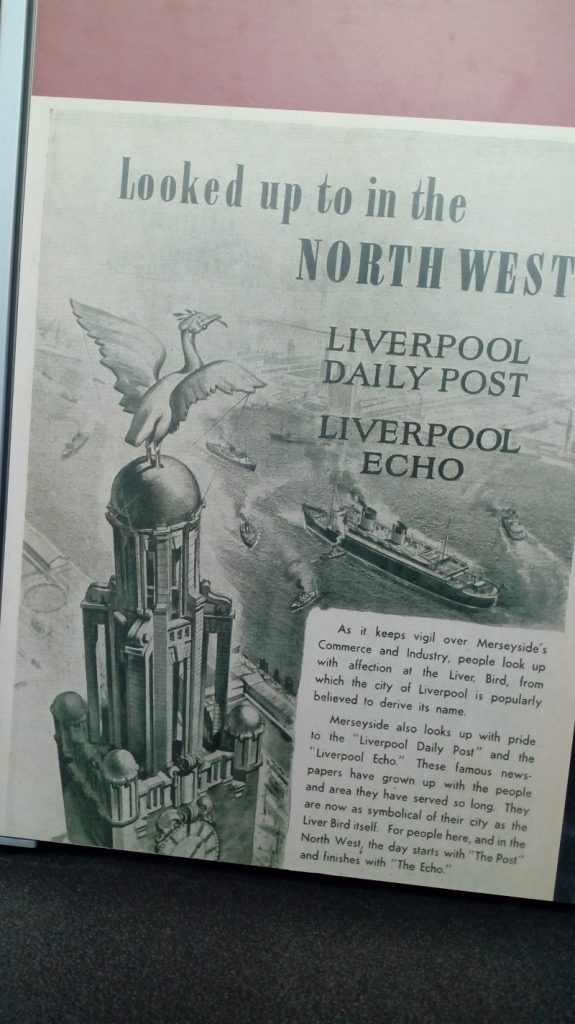

The conversation flowed naturally. More beer was brought. It all felt very relaxed. Memories of Liverpool came up; that Liverpool of the nineteen-sixties from where, extraordinarily, so many interesting things came out at that time. The Beatles, of course, but also those verse-makers, Adrian Henri, Roger McGough and the poet himself, that celebrated group whose anthology, The Mersey Sound, published by Penguin in 1967 has remained in print ever since, selling over 500,000 copies. It is still the biggest-selling poetry anthology of all times in any language. Quite an achievement, for someone who was put originally in his school’s lowest-ability set. Food for thought for all of us.

The Liverpool he was born in was an impoverished place, mercilessly punished during the War, as German planes attacked what was then one of Britain’s major ports. He remembers, as a child, playing among the ruins of houses and empty lots where people’s dreams had been shattered by bombs. The rebuilding was slow, but a new spirit emerged from the ashes of devastation. Apocalypse gave way to phoenix-like rebirth. The endless cycle of death and life. The city, like Britain itself and Europe at large, emerged cut to size. No more second-city of the Empire, no more being the gateway to New York, soon no Empire at all. An old world had -literally, again- been bombed out of existence. England had emerged triumphant but severely scarred and humbled. But Attlee’s surprise victory in the first post-war election gave way to a new optimism that came from the dignity of those people who had stoically withstood the rage of hell and were not ready to accept to be short-changed.

I asked the poet about his relation to the city and about that celebrated Scouse scene, whether it was as exciting as it has been made to be, or if it has been magnified by legend and time. His answer was that it probably was, although back then it did not really feel so. It was just life. The street where he grew up was pulled down some time ago and it is now a sad little modern cul-de-sac in the Sefton Park area, now as then a poor side of town. But, apart from his street, the neighbourhood still stands pretty much as he would have seen it then: endless terraces of classic northern two-ups, two downs. It´s near Toxteth, where there were famous riots in 1981.

By the nineteen-nineties, however, Liverpool seemed to have sunk into a splendid decay. I used to visit it then and I remember it as an interesting place, with grand architecture and that wonderful river, the Mersey, which gives it a cosmopolitan feel that land-locked Manchester lacks. Liverpool was indeed the second city of the Empire at one point, and it shows. The New York liners used to set off and arrive in Liverpool before the advent of the plane, and that has left captivating traces: grand hotels and magnificent civic buildings. Liverpudlians are friendly and their accent has always sounded to me beautiful and sexy, a bit like that of Cadiz or Seville, in my native Spain. Indeed, Liverpool has always seemed to me be Britain’s Seville, a place with attitude and personality, confident in itself and not caring much about what other people may think or say about it.

The Sefton Park area, where the poet grew up brings to mind the work of the Assemble Collective, which won the Tate Gallery Turner Prize some years ago. Their “interventions” in nearby Toxteth are an example on how art can change things, just like poetry did for Brian Patten. After leaving his mother´s home, he moved to 32 Canning street, in the more salubrious Georgian Quarter of Liverpool. I visited the address recently with a friend working on a short TV documentary about the anniversary of the publication of the Mersey Sound anthology. There were cigarette butts and empty cans of beer on the front steps, and I took pictures of it all, thinking it was all very “poet maudit”. One of its current inhabitants came to see what was up. He was a good-looking boy who said he shared the house with nine more students. Disappointingly, they had never heard of the poet, which is normal, I guess, for poets are a quiet lot. They are, in Shelley´s famous words, the “unacknowledged legislators of the world”. They are often ignored in their time, but their influence eventually soaks in. It is a shame, nevertheless, that the council has not put a blue plaque marking the place. Perhaps they only do so when someone dies.

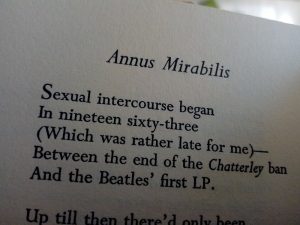

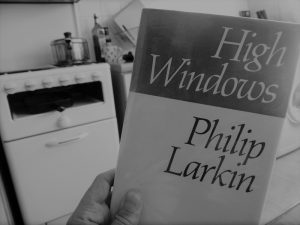

The poet was very much part of that Mersey Beat scene. How could he not be? He was young at the onset of the decade when sex was invented, “between the end of the “Chatterley” ban and The Beatles’ first LP”, as Philip Larkin famously said. Although he was a bit younger than them, he went to the Cavern club, and saw the Beatles play live there .

New customs needed new forms of verse as well as new forms of music and ways to approach sex. The poet was there to report from the front. He read poetry in bohemian cafes and at the Everyman theatre too. His poems gradually gained depth as he matured and life’s complexities and contradictions emerged. We talked about childhood and parents, how black and white certainties turn grey as time goes by.

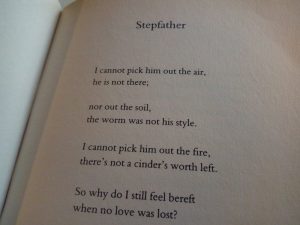

That drab English world of the nineteen-fifties, which he was so determined to escape, was to be later reassessed, and his neglect of it felt like “a kind of betrayal” of those who passed away like the autumn leaves of the French song: “sans faire de bruille”. But time the destroyer is also time the preserver, as Eliot wrote, and if it takes away happines, it also takes away grief. So, the poet doesn’t look back in anger to whatever discord he left behind when he moved out of Wavertree Vale, his mother´s home in Sefton Park. The poet’s relationship with his mother and his stepfather; the pain and memories that her death awoke in him, are well recorded in that volume that I was reading when my own mother died in a hospital bed in Barcelona. Our experiences were different and yet the poetry spoke to me as clearly as if the poet’s words had been directly addressed to me. As he so rightly said, the poetic “I” is always a “we”.

Armada, the poet agreed, was a change of tone and a turning point in his work. He had discovered a deeper accent. The mother’s death brought home for him a greater compassion for a world that perhaps he had till then refused to explore.

But he did not like to dwell on all that. Whatever sadness or trauma he experienced then, the poet seems to have efficiently cleansed by writing poetry about them. He moved on to tell me about a Polish lady that lived down the road from him and who played a role in his sentimental education. She must have been one of the many refugees that came to Britain, escaping from the Iron Curtain that so cruelly fell over Europe after the War. Apparently, in cultural terms, she was quite a cut above the rest of the neighbourhood, a traditional working-class area where people were not inclined towards literature and the arts. Workers had that aversion to culture that often stems from a misplaced sense of identity and pride, out of a fear of being thought pretentious, better than they are. This is the same mindset that keeps bottom-set students in their place.

However, by contrast, the Polish lady had books, European ones, and foreign records that she played. She came across as a breath of fresh air. I identified with the appeal that a character like that would have had on a young man looking to break those invisible walls that tried to constrain him firmly within the bounds of his class. He sought to expand the possibilities opened for him, curious to find out his own way, escaping from the paths set for him by those who came before.

The afternoon went by as we drink our beers. The poet needed to leave Liverpool and move on as a necessary condition to grow. I had the feeling that he isn’t too keen to be forever associated with “the Liverpool Poets” brand and to be pigeon-holed. We discussed a bit what it is that drives one to write poetry: the urge to understand oneself, he said, and the world around, as well as an urge to break free from that very self and shatter the walls that trap us in there. Again, that urge to turn the “I” into the “we”.

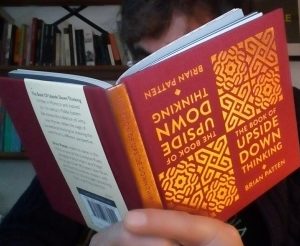

He gets to see the world quite a lot these days, visiting many European cities and further beyond. He’s quite fond of Essaouira, in Morocco, a perfect setting to inspire him one of the works he was then currently engaged on: his own translation/interpretation of the stories of Nazrudin, a semi-mythical wise fool with roots in the Sufi tradition. The “Book of Upside Down Thinking”, as the title that work received when it came out, is a marvellous collection of witty verses that aim to make us question the way we look at the world, for there’s always another side, another point of view from which to look at things. That’s one of the lessons Nazrudin’s tales teach.

The poet’s wife, Linda, is a freelance travel writer for several publications and thus they often get free tickets to visit the places she reviews. The mention of a wife brings to my mind my friend Helena, the one who used to live in New York and discovered the poet for me when she could not find “Armada” in the bookshops of the city that never sleeps. I called her to tell her that I was going to meet him and she, quite calmly and only in half-jest, announced to me that she intended to marry him. “She’s dead serious”, I said as I relayed this story to him, “she already refers to you as her husband and, as she is a widow, she claims there’s no legal impediment”. The poet laughs, secretly pleased.

He goes back inside the house then and comes back carrying a handful of sheets with some printed poems. They are unpublished manuscripts from another book he’s working on. One of the poems is beautifully poignant, a kind of elegy about somebody’s death. There are some Mediterranean references, to rosemary, thyme and such plants, I don’t remember well. I read it silently to myself, but he insists that I should do it aloud, a request that both flatters and frightens me a bit. It feels such a responsibility. I read it first silently, anyway, to get the correct rhythm and, as I do so, I am overcome with emotion. I feel tears flood to my eyes. “But this poem”, I say, “seems to be about me. How could you know?”.

I tell him about my best friend Miguel, whom I met at school at the age of 9 and of his death to cancer and HIV at the age of forty. I say it´s a poem that resembles me, quoting “Dead Leaves”. It uncannily speaks about the everlasting sorrow and pain at my loss, but also of the joy of having met Miguel and of him having now merged with my love for him. I realised then that I had just quoted the poet’s words engraved on my mother’s tomb. He smiled. “No, Raffy”, he said, “I didn’t know about you and your friend, of course. The poem is about a friend of mine who also died. Someone who lived in Majorca, hence the Mediterranean theme”. The poetic “I” is indeed always a “we”.

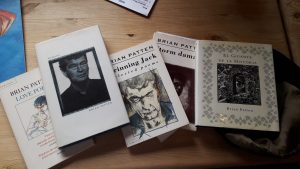

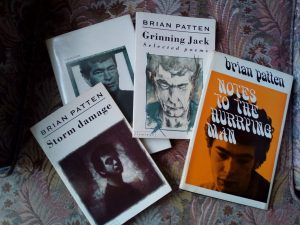

I decided then to call it a day, not wanting to tire the poet or intrude more than necessary in his routine. However, I tell him I have brought a collection of his books for him to dedicate to me. One is already signed. It´s a hard copy of “Armada” that I found many years ago at a secondhand bookshop in Cambridge. I bought two. One for Helena and one for myself. The poet remembered signing a pile of them on a reading occasion ages ago at the university town. Perhaps the publisher had been too optimistic and were never sold; or maybe their owner died and the heirs, ignorant nephews, nieces or children, just auctioned the departed person´s belongings.

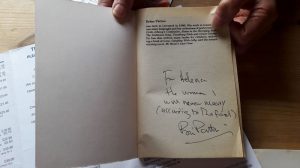

“Oh, well! So, you won’t marry my Helena then, but please sign this for her”, I asked the poet, producing a volume of his love poetry.

He signed the books playfully, patiently, understandingly, pleased at my naif enthusiasm. I read the dedication in the love poems for my friend: “For Helena, the woman I won’t ever marry”, he had written, and then added naughtily: “or so Rafael thinks”. I love this. “I think we are alike you and I, we just like different meat”, he said, giving me a wink.

I said farewell repeating those famous Baudelaire words: Mon semblable mon frère as we gave each other a big hug. I really felt, after that encounter, that he is indeed my likeness, my brother. We promised to meet again.

I made then my way down the garden, and walked back to the harbour with a feeling of joy at how beautifully the afternoon had gone by, warmed by the poet’s unguardedness, his openness, his offer of friendship to a total stranger. Down at the jetty, I rang the bell to call the ferry across to fetch me from the other side. A lesbian couple joined me, and I exchanged some pleasantries with them as we waited for our Creon. They were renting one of the cottages by the river front. They are from Bristol, one teaches English at a secondary school, the other takes care of the kids. The teacher asked me if I am also lodging in Dittisham and I told her about my visit to the poet. She didn’t know he lived there and she was quite chuffed to learn about it. She said she knows his work well and e teaches one of her favourite poems by him: “ Poem Written in the Street on a Rainy Evening” which I could not quite recall but we find in one of my books. We read it as we crossed the Dart. The sun had come out, the afternoon had brightened up. It seemed somehow out of place to read about rain in city streets.

Once on the other side, I walked back towards Galmpton along the lane with the birds singing unseen in the overarching branches of the trees that form a kind of triumphal arch over the road. The little steam train ran past, whistling, and when its noise subsided, silence took over the silver estuary, luminous in the late afternoon sun. Everything was beautiful and some other verses from Baudelaire came to mind: “ici tout est calme, luxe et volupté”.

It was one of those perfect days when one wishes time stood still; days when the “I” dissolves in our love for the “we”, days when stories begin that one wishes never to end.