War and Peace in Pozoblanco

The history of Spain, like that of most of the world, is rich in terrible events. Of all those episodes, one of the most painful is the Spanish Civil War that took place between 1936 and 1939. It’ s a tragedy that still pervades and poisons national life, as the transition to democracy of the mid-seventies did but paper over the old cracks.

After the triumph of the fascist rebels in 1939, General Franco ruled Spain with a merciless iron fist for forty years. There was no compassion for the enemy, which was ruthlessly annihilated. After his death, a gradual process of political opening up took place. It led to the Spanish constitution of 1978 and the return of democracy. It was a difficult balancing act trying to accommodate the interests of everyone. Concessions had to be made by all. Unfortunately, this meant tiptoeing around the excesses of the past to achieve national reconciliation.

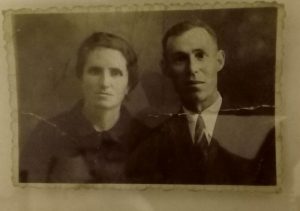

My father was five years old when the conflict broke out and eight when the loyalist Republicans were defeated. Despite this tender age, he has vivid memories of the time: “How could I not remember the war?”, he answered once that I asked him over lunch. An eight-year-old boy was already an adult in those days, when people started to work at the age of nine. There was no time left to be spoilt or for cosy overprotection as they were needed to toil in the fields.

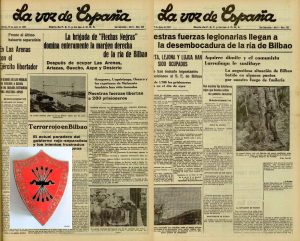

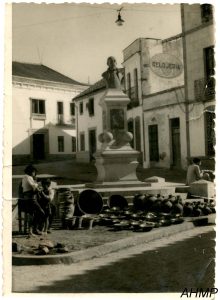

When war broke out, my grandfather, Manuel Casillas was running a newsstand in Pozoblanco’s main street. Among others, he sold the right-wing press. This would not be anything extraordinary in times of peace, but in the context of the war it was going to put his life at risk.

Pozoblanco kept loyal to the Republic when the fascist uprising took place in 1936. General Queipo de Llano had joined the rebel military and his troops quickly took control of Seville, Córdoba and most of Andalucía. However, he failed to take the Pedroches Valley, of which Pozoblanco is capital. From then and for the three years that the war lasted following the inconclusive coup d’état, the area would become a savage frontline. Pozoblanco resisted till the end, falling only at the end of March 1939, two months after the fall of Barcelona and shortly before the final fall of Madrid, the martyr city of Pasionaria’s legendary “No pasarán”.

From his captaincy in Seville, Queipo de Llano acted as a colonial viceroy. He had learned from Hitler and Mussolini the power of radio to spread propaganda and every evening at ten he broadcast from Seville pep talks to undermine the Republican morale. He used tasteless, rude language with his fluty voice, the voice of a repressed gay man.

But Pozoblanco resisted him when he launched his attack in 1937, which ended up in a heroic victory for the troops led by Catalan general Joaquín Pérez Salas. This important Republican success was somewhat obscured by the simultaneous triumph of the loyalist troops at the battle of Guadalajara, which prevented the fascist rebels advance towards Madrid. Queipo de Llano was forced to a humiliating retreat to the Sierra. For the remaining of the war the Valley would become the front-line between the two belligerent sides.

In this context, the sale of conservative papers at my granddad’s newsstand was clearly an affront to the Republican authorities. Such fascist-supporting press had been banned as they rightly considered it enemy’s propaganda. According to my dad, all the family were staunch Republicans, including granddad Manuel, who had even been in trouble for supporting the Republic. However, he had studied, like so many other children in town, at the school run by the Salesian fathers and this had given him some respect for the Catholic Church.

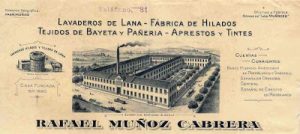

This historian tells us that on the second half of the nineteenth century, the town´s society, like elsewhere in the country, had split in three groups: liberals, conservatives and republicans. The first two groups were both conservative and all but indistinguishable, except on their approach to religion. Liberals were against the excessive influence of the Catholic church on national politics. They considered religion to be a private matter. They had hugely benefited from the different expropriations of church lands that had taken place throughout the nineteenth century and had used those profits to invest in the textile industry that supplied the last Spanish colonies: Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines, and when these were finally lost in 1898, to the Peninsular market.

Pozoblanco had been a centre of textile manufacturing long before the Industrial Revolution. There were three mills in the town producing high-quality tablecloths, serviettes and cleaning cloths. Before the arrival of the railway, they had used a network of mule drivers that distributed the merchandise and connected with the export ports. As everywhere else, the arrival of the railway to the Pedroches acted as a transmission belt to those new ideas that spread quickly throughout Europe: Darwinism, Marxism and Freud, all of which were on a collision course with the privileges that the Catholic Church had enjoyed in Spain since the times of the Christian Reconquest.

The Peñas family had thus been Republican people, according to dad, that is progressive people. My great-grandfather had been a miner, a profession in which the Spanish Socialist Workers Party, which had recently been founded by Pablo Iglesias, had logically gained their support, as it raised itself as a defender of workers’ interests against those of the traditional powers. The Catholic church, seeing its position jeopardised, allied itself with the landowning class to conspire against liberals, republicans and socialists in a crescendo of hostilities that would culminate catastrophically in that terrible Civil War of 1936-1939.

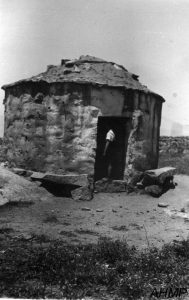

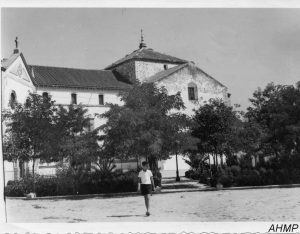

My grandfather Manuel had thus fallen into the orbit of those ultraconservative Salesian brothers that, as it has already been said, had as mission to use education as a Trojan horse for their ideas. Against all his family tradition, he had become rather sanctimonious, something for which he would be duly rewarded after the war when he would be given the post of caretaker of the Sanctuary of Our Lady of the Moon, patron saint of both Pozoblanco and the nearby town of Villanueva de Córdoba. This Madonna has a small chapel devoted to her a few miles from the town on the road to Villanueva, a paradisaical place of soft meadows where Iberian pigs roam together with fighting bulls and pure-breed horses.

Selling the conservative press was thus a serious crime in the Republican zone, and my grandfather should have known better, but perhaps his sanctimony got the better of him. When he was found out, he had to flee for his life to seek refuge in a field with all his family. The story goes that my grandmother had had a suitor that she rejected for my granddad and that it was this man who, on getting wind of where the family were hiding, denounced him to the authorities, forcing my grandfather to run away with his older daughter, my aunt Regina. In those days of revenge and retaliation, the hills and fields around town were crowded with people who had fled the assassinations that took place daily, indiscriminately and without trial. My father says that when that spurned suitor turned up in the cabin where they were hiding, the horse he was riding threw him off the saddle and he broke an ankle, which was the cause of much mirth and aggravated the resentment of the man. Somehow, he managed to ride back to town and he gathered a lynch party, but the head of that squad turned out to be none other than Félix, my grandfather’s brother, a Republican, like the rest of the Peñas family. When he found out who it was that they were chasing, he said he could not kill his own brother, thus saving the family. After that, they returned to town and granddad was allowed to keep his newsstand on condition that he didn’t stock the forbidden papers.

Such personal revenges disguised as political were very common on both sides of the civil confrontation. It is one of the most awful consequences of all armed conflicts in general and of civil ones in particular, in which often members of one same family take opposite sides, for economic reasons or simply on account of old grudges between different family branches or even between brothers.

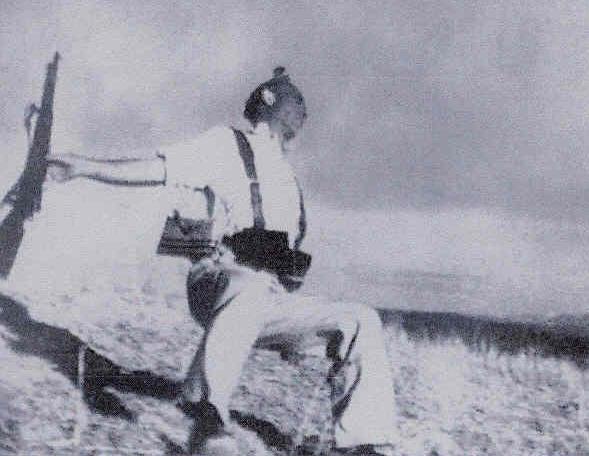

Once the war was over and the fascists finally took control of the Pedroche valley, a fierce repression was unleashed against anyone who participated in the Republic, no matter how peripherally. This forced a new exodus towards the nearby hills. That old suitor of my grandmother, like so many others, was killed unceremoniously swept by an unstoppable orgy of repression and revenge. Among those who took to the hills, there were gangs that organised themselves like the old legendary bandits that had roamed the Sierra Morena range in the nineteenth century. They were called “maquis”, a form of underground resistance to the victorious fascist regime that would go on for several years, until they would finally be ruthlessly eliminated by the “Guardia Cívil”, the Spanish rural police.

One of my French cousins, Jeanine, who came to study in Barcelona in the late seventies and then married and settled there in a new wave of family migrations, told me the story of someone known as “Caraquemá” (Burnt Face). She had heard about him from our aunt Nicasia, with whom she lived several years when she first came to Barcelona.

This man was the leader of one of those “maquis” squads. They lived in the wilderness of the sierras, a territory which they usually knew well as, before the war, they had often been shepherds in the region. This allowed them to escape detection for many years thanks to their superior knowledge of the rugged terrain.

Those “maquis” often turned up by the area surrounding the sanctuary of Our Lady of the Moon, where the Peñas family had moved when my grandfather was appointed custodian of that little shrine. They refused to accept the fascist victory and waged their own guerrilla war against the enemy. They acted as self-styled gangs of Robin Hoods, claiming to steal from the rich to give to the poor, although it was not always clear that they had such altruistic purpose. They often stole sheep to eat but also just to damage the economic interests of the landowners who had won the war. Gradually, the “Guardia Civil”, the Spanish rural police would drive them out of their hides, ambush them and killed them all.

However, my dad says that both those outlaws and the “Guardia Cívil” that chased them often came from the same humble origins and would actually meet sometimes to share food and stories in the no man’s land of the woods. Nothing is black and white in life, as history books would like us to believe. Historians do not normally care much for anecdotal accounts that may be but exceptions to the rule. They write from documents and sources that are already accommodating reality to the official version of events. I was surprised to learn of this furtive interaction between what were supposed to be mortal enemies.

“Caraquemá” was the last of the “maquis”. According to what my now sadly departed aunt Nicasia told to my cousin Jeanine. The older Peñas sisters, my aunts Regina, Ana and Nicasia had met him many times while they were tendering to their sheep in the neighbourhood of the sanctuary of Our Lady of the Moon. He never gave them any trouble. On the contrary, they used to offer him food and water, for which he was always very grateful.

It seems that, in order to lure him out of his hideaway in the hills, the Civil Guard used as bait Caraquemá’s wife and older daughter, forcing them each night to roam the woods and ridges crying out his name, urging him to give himself in so they would not kill them. It´s hard to imagine a worse torture for those two poor innocent women, but that´s how the Spanish Guardia Civil operated in those days.

In happier days, my aunt Regina had been good friends with the unfortunate young daughter of the famous runaway. She was called Rafaela and she was totally devoted to her mother. My aunt says that it was not him who had a burnt face, but an old ancestor. However, the name had stuck with successive generations of the family. They were shepherds and as such had always lived in the hills caring for their animals. At some point they had come to live in town and, as they were dirt poor, they had built themselves a shack out of tree branches in a street called Calle del Ángel, right in the centre of Pozoblanco. My aunt Regina had visited them there and she says they lived in abject misery. It seems that one day, pressed by sheer hunger, that man stole a chicken from one of the neighbours to give it to his starving parents. Someone must have known about it and reported him to the police. He was arrested but was left free with just a reprimand until a second chicken disappeared. He protested his innocence to this second theft, but he was not believed, so he ran away to the hills and joined those “maquis” who were in hiding since the end of the war. From then on, any theft in town was attributed to “Caraquemá”, even though often he had nothing to do with it.

Night after night the Guardia Civil took the hapless women from their poor home and forced them to roam begging him to give himself in but, as he never did, one night they were just shot at a point between the shrine of Our Lady of the Moon and the railway station of La Jara. My aunt Regina married to my uncle Antonio Egea soon after and they moved to Bordeaux, but she has kept vivid memories of this horrid episode. She remembers how sweet the girl was and how utterly devoted to her mother she was. She always went with her wherever she went. It seems that she tried to prevent the “guardias” from killing her mother by throwing herself over her when they were going to shoot her and that she died like that, embracing her mother in a futile attempt to protect her.

It´s hard to believe such cruelty. They were both very nice people who did not deserve at all the mistreatment they suffered at the hands of the Guardia Civil. Their only crime had been to be poor and to dream of a better life. My aunt Regina has never been able to forget them. She remembers them shouting in the middle of the night: “Give yourself in! they are going to kill us!”. They knocked on their door at the sanctuary where the Peñas family lived begging them for water. I asked my aunt Regina what happened to those guards who had killed the women and whether she knew them. She says that sure she did and that the one that shot them dead turned mad and ended up in a psychiatric hospital, unable to cope with what he had done, following orders from his superiors. Summary executions such as those were common currency during the post-war period, when human life was all but worthless.

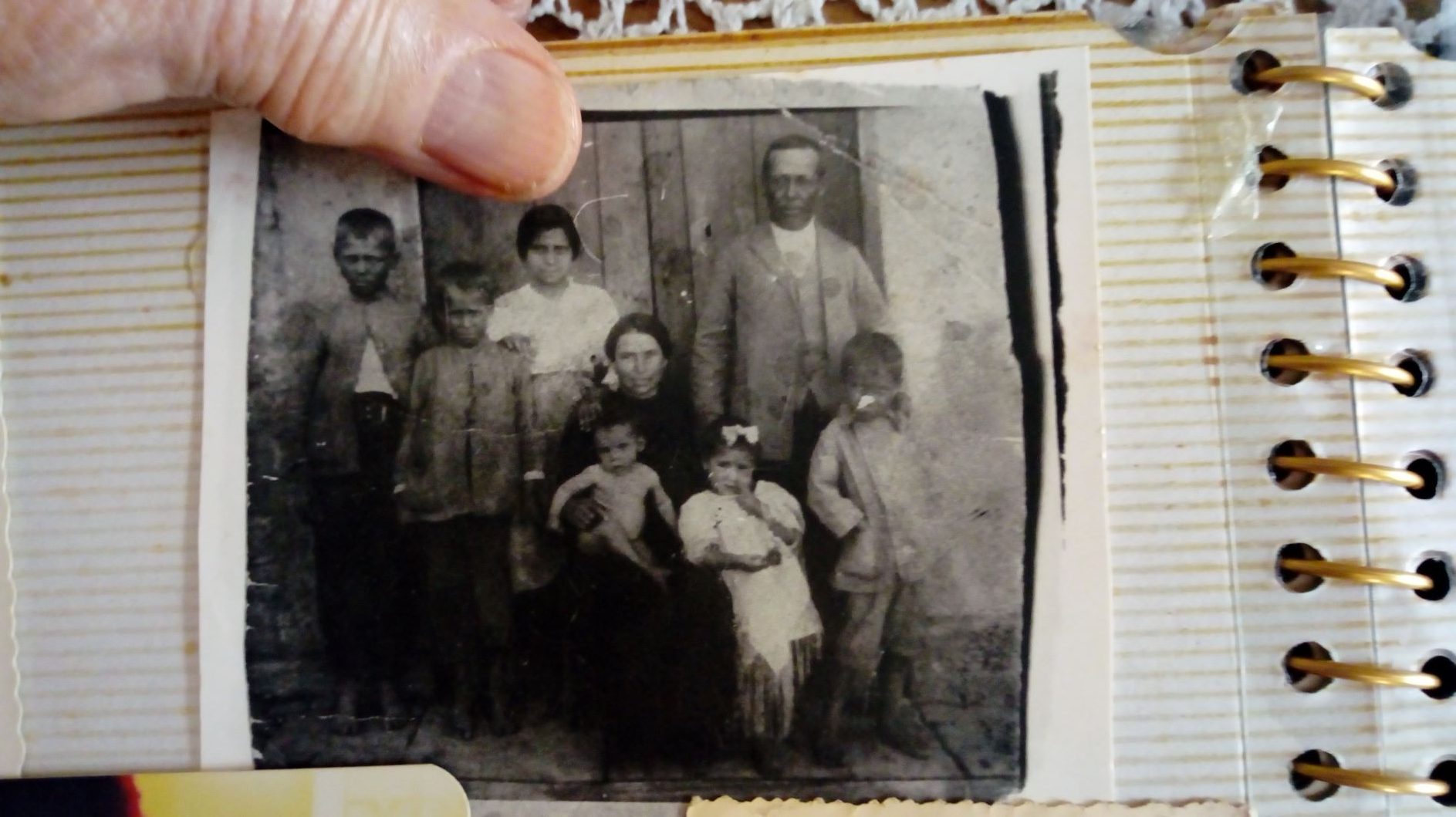

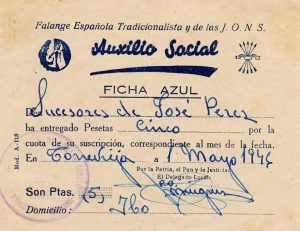

If life had been hard during the war, it would get worse in the years immediately after. The Peñas family, my dad, his six sisters and his young brother born in 1944 scrapped a living thanks to the animals tendered by my grandfather Manuel working for the board of trustees of the Sanctuary of Our Lady of the Moon. The post as “santero” (custodian) that my grandfather had secured was not remunerated, but it allowed him the benefit of cultivating some land and to rear some animals. Moreover, my grandmother had the “privilege” of begging from house to house offering some religious cards with the image of the Madonna, an occupation that she found humiliating but, as the saying goes beggars cannot be choosers, quite literally in this case. I suppose now that activity could be described as “fund-raising”.

But, like it or not, my grandmother could not be too picky and had no option but take her mule and go knocking on doors offering her image-cards. As times were difficult for everybody, she would rarely get any cash, but would be offered butter, olive oil or other produce. She was also given old clothes that she would then mend and patch with great expertise. However, she would more often than not just be told to come back another day because people had nothing to offer her on that occasion.

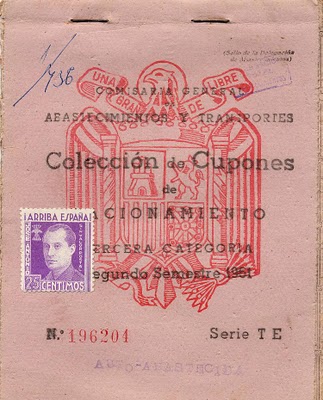

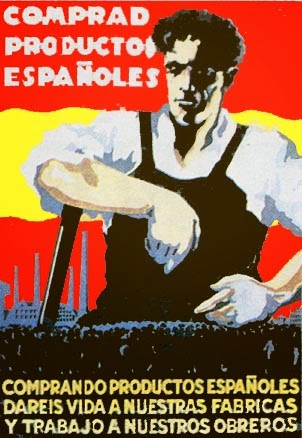

The war had halted agrarian and industrial production for three years. Also, the Second World War began in Europe soon after, which meant that there was no access to trade and the raw materials needed for the reconstruction of the country, even if there had been money to purchase them, which there wasn’t. To make things worse, the victorious General Franco surrounded himself with a cabinet of military ministers who were totally incompetent, moved more by ideology than by any pragmatism. They had but a hazy notion of basic economic realities. They thought rather foolishly that Spain could and ought to be self-sufficient. They designed a disastrous economic programme of recovery based in autarky, which led to scarcity, hunger and a burgeoning black market from which a few unscrupulous people profited.

In time, that crazy programme had to be abandoned as the national GDP plummeted to 40% of that of other European nations. In those circumstances, Franco got rid of those “ideological” ministers and replaced them with “technocrats”, young neoliberals who would open the country to foreign investment once the World War was over. This young guns devised economic development plans that would little by little yield some results. However, agrarian output would not reach the levels enjoyed before the Civil War until 1958.

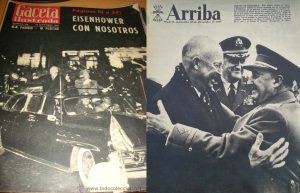

By that time, many Andalusian peasants had already started to leave their homeland. They migrated to France, like my aunts Josefa and Regina , to Germany or even further afield, crossing the Atlantic to Argentina, Venezuela and Mexico. The new economic order was backed by the United States, with whom General Franco signed some defence treaties in 1953. In exchange for an injection of foreign capital into the Spanish economy, Spain would allow the Eisenhower administration to have three military bases on Spanish soil. A middle class would eventually begin to emerge as the economy was kick-started by the combined effect of trade liberalisation and North-American investments.

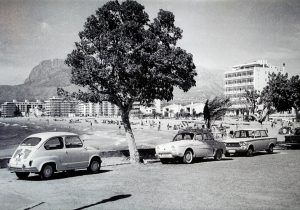

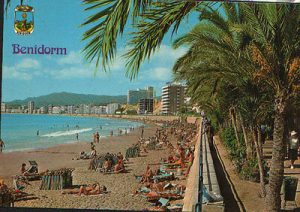

This would create its own problems, as the corrupt and inefficient system was not going to be able to meet the greater expectations of the population. Moreover, the development was unequally distributed throughout the national territory. Investment was concentrated on certain areas such as Catalonia, the industrial north, Madrid and along those coastal areas that had been identified as suitable to be developed as tourist resorts. The working classes from Northern Europe would be encouraged to spend in Spain the statutory paid holidays that were institutionalised everywhere. Those sun-starved peoples of the North would flock to Spain seeking that elusive sunshine that their developed economies could not provide for them.

Thus, that blazing scorching sunshine from which my ancestors had studiously protected themselves became a desired commodity from which large sums of money were made, bringing much-welcome foreign currency to the cash-strapped country. The result was that unprecedented movement of large swathes of the population from Spain’s rural areas to those new poles of development and modernity. I remember the irony with which my mother used to look at the exposure of flesh roasting on the Catalan beaches: “and there were us”, she would say, ” hiding ourselves from so much sun as we had in the fields!”.

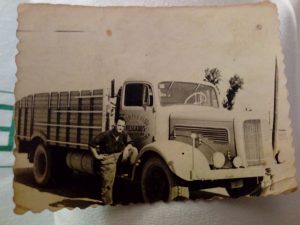

So, thanks to the US backing, after a disastrous decade of stagnation when prices trebled, a brutal black market thrived and poverty spread throughout, the new regime began finally to take its first stumbling steps towards economic recovery, leaving aside that stupid pretension of self-sufficiency. As they grew up, the young members of the Peñas family understood that there was no future for them in that old subsistence agrarian economy, so moving abroad or to those new development areas fostered by the regime became increasingly an attractive proposition. Once married and with children of their own, towards the end of the fifties and early sixties, they started the exodus, seeking better opportunities for themselves and more education prospects for their children, escaping from the hardships and travails of the rural world.

As time went by, that prosperity would eventually also spread to Pozoblanco. In 1959 the COVAP was founded, the Pedroche Valley Cooperative, a successful entrepreneurial effort that has brought wealth to the town by making a more effective use of the agrarian resources available as well as a more even distribution of the income generated by them. The Cooperative became a strong player able to negotiate and impose its conditions to the powerful retailers thanks to the pooling of resources and the know-how necessary to access markets, both national and foreign.

Unfortunately, the success of this initiative took some time to materialise. Many inhabitants of the Pedroche Valley, like many other Andalusians, had felt all but abandoned by the regime´s concentration of the investment of Uncle Sam´s generosity in certain areas, leaving others exposed, trusting that migration to those poles of development would eventually even out and correct the imbalances caused by their public investment policies.

My grandfather, Manuel Peñas Casillas, died at the age of 57, the fifth of May 1955 after a long illness. My grandmother did everything she could to save him, spending all the money she had to offer him the best treatment available, including an operation at a Madrid hospital by an expert surgeon she had been recommended in Cordoba. She found herself in a tricky spot and she had to take difficult decisions. To make things worse, some years before he had begun to feel ill, my grandfather had been sacked from his position as custodian of the Sanctuary of Our Lady of the Moon, where the family had found a living of sorts during the difficult post-war years. Migration to Barcelona presented itself as the way forwards.

To a greater or lesser extent, all the Peñas managed to reach that greater well-being that they sought when they left their land behind, each of them contributing to what has often being called the “Spanish miracle”, that diminished and less successful version of the German “Wirtschaftswunder” or the Italian “Miracolo italiano”, the rapid reconstruction of Western Europe after the disasters of World War II, a miracle caustically mocked by Spanish film director Luis Berlanga in his “Bienvenido, Mr Marshall”. This is a comedy in which the people of a Spanish typical town get high hopes when they are told that the American president himself is going to visit their town. In the end it all amounts to a rapid crossing of the President´s motorcade at great speed, without slowing down, let alone stopping for them.

Ironically, it would be the family of my uncle Juan and my aunt Ana, those who came back to Pozoblanco after a testing of the waters in Barcelona that left them unconvinced, who would eventually thrive the most, thus proving that given the right conditions – universal access to education and a level playing field for everybody – progress was possible everywhere.

The reason why the family was kicked out from the shrine of Our Lady of the Moon was a dispute over some firewood. There had been apparently three or four dead oak trees near the little stream that crosses the land around the little church and my grandfather asked the Board permission to cut them down to make charcoal so the family would have fuel to keep warm in the freezing winter. He was granted permission but, as charcoal making is an elaborate and difficult process that requires a skill that my grandfather did not have, he called some men from the town to come and do it for him. It seems that, whether by a misunderstanding or in bad faith, these men cut not just the dead trees, but also some others my granddad had not been given permission to cut.

The board of trustees became furious when they learned about it, considering it an act of gross misconduct on the part of my grandfather, so they decided to remove him from the post. At that time, charcoal was the main fuel in the Valley and thus trees were an important source of wealth. To cut them without the owner´s permission was a serious crime.

The expulsion from Paradise took place in 1949, a year before the marriage of my aunt Regina and my uncle Antonio Egea, so many people bitched that my granddad had cut the trees to sell the wood in order to pay for her trousseau and her endowment. The family had to come back to their house in town but, having lost the few “privileges” they had enjoyed till then, most of my aunts had no other option but to hire themselves as domestic service, a common professional opening for the daughters of the peasantry in those days. They worked for the rich houses of Pozoblanco, among which took pride of place the Castro women, popularly known in our family as “las Castras”, a very demanding sort of employers.

By the time my grandmother and my uncle Manolo moved to Barcelona, most of her daughters were already married and had left Pozoblanco. My aunts Regina and Josefa moved to Bordeaux, in France, and the rest to Barcelona. As we know, Franco´s “technocrats” had no development plans or investment priorities at all for the Pedroche Valley or similar areas, so all that surplus workforce had to migrate elsewhere, to those shiny brand new tourist resorts along the costas where the tourist boom was about to begin, as well as to the old industrial cities of the north.

Thus, the agrarian reform, the great aspiration and bone of contention for all Spanish liberal governments throughout the nineteenth century, would happen not by means of a distribution of land as it had been dreamed by the socialists, but by default, when a critical mass of dispossessed casual workers simply moved out to the cities, leaving vast areas of the Spanish countryside depopulated, as families sought a better future far away from their homelands.

The memory of the war was set aside in people´s minds once money started to flow and they gained access to flats with indoor toilets, kitchens furnished with all mod cons, paid holidays and the small SEAT cars that would become ubiquitous on the Spanish roads for the next few decades. In those circumstances, people started to look forward to the future and were happy to leave the dead to rest.

Until now, when a new generation not blinded by that material progress, has begun to question the silence imposed on the abuses of the Francoist troops during the war and the regime’s brutal repression throughout its long rule. Laws of “memoria histórica” have been passed by the Spanish Congress of Deputies and the issue is regularly discussed in the press as this new generation increasingly demands to know what happened to all those relatives lost to everyone, buried in mass graves along those same country roads where people drove their SEAT cars.